The historic importance of Gay Comix, Part 2

This week, we return to the archives for another examination of the historically important Gay Comix. This time, we’re turning our attention to 1981’s Gay Comix #2 – published a whole year after the first issue.

Still edited by Howard Cruse, the sophomore edition offered readers another 36-page anthology of strips from pioneering queer creators, some returning from the first collection, others making their debut in the series.

CONTENT NOTE: This column openly discusses sex and sexuality. Images may be risqué, and may be considered NSFW.

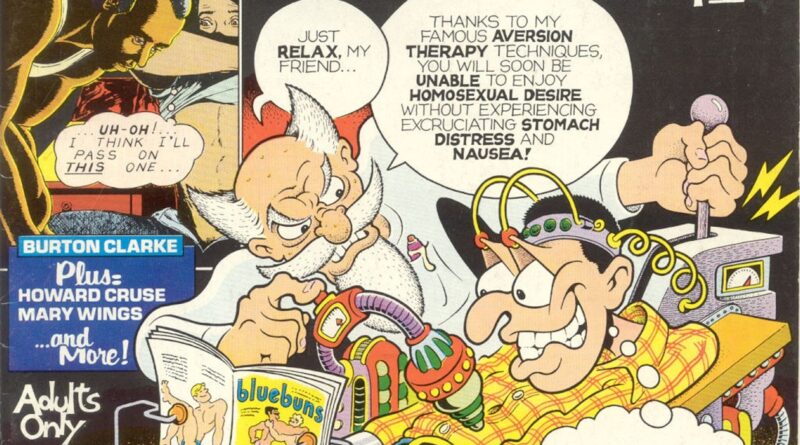

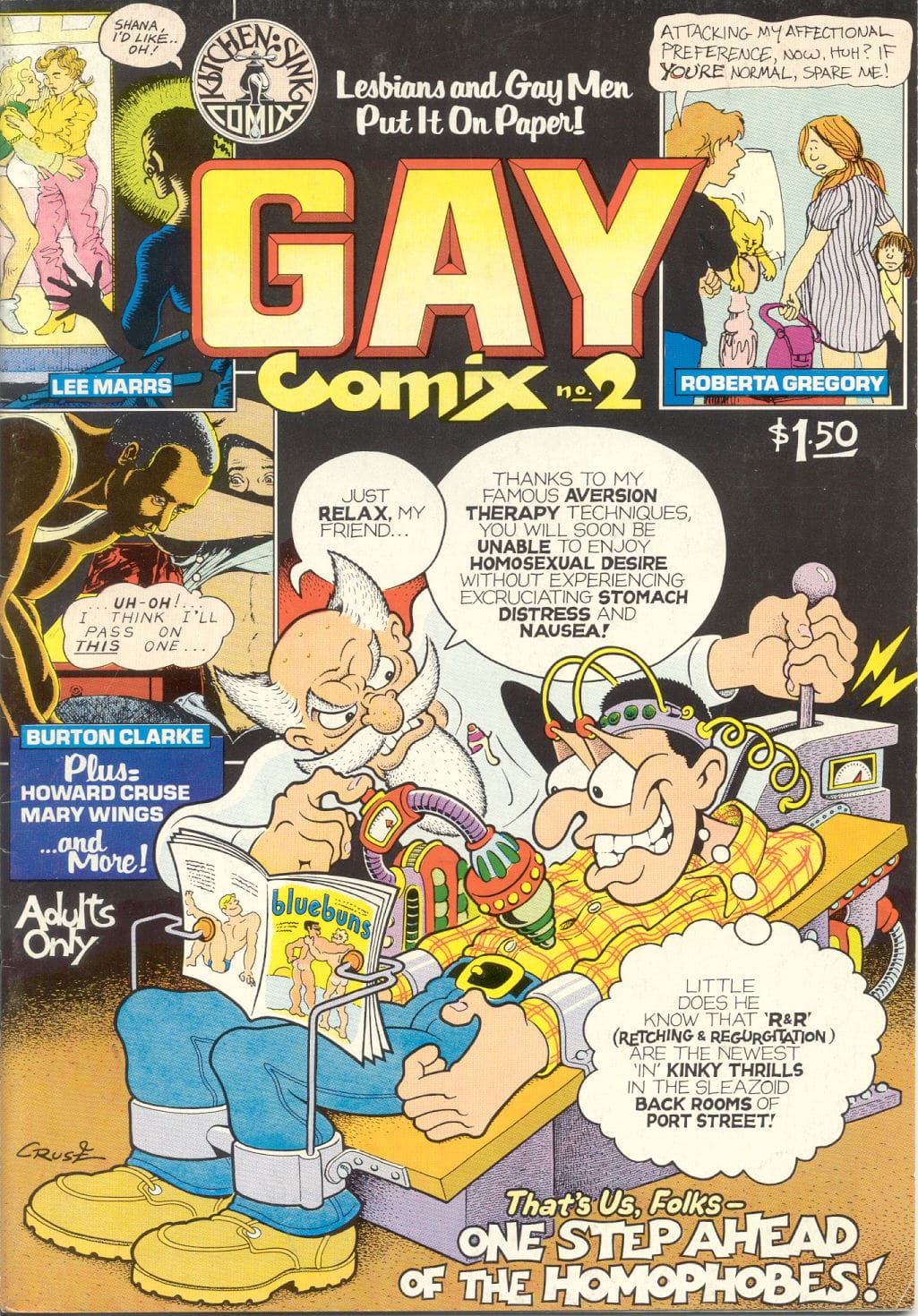

Cruse himself provides the cover for the second issue, with a cartoonish gag that seems to draw inspiration from the likes of humour magazines MAD or Cracked, with a satirical swipe at conversion therapy. Sadly still a blight on LGBTQ+ people more than four decades later, Cruse’s cover turns the homophobic practice on its head, with the recipient all too into a very specialised process that happens to replicate a new underground kink. It’s a dark joke to subvert a dangerous, harmful, real-world practice – a real “if you don’t laugh, you’ll cry” moment. The cover also offers a few panels of art taken from the black-and-white interior pages, brief teases of what lies in store for readers, and rare glimpses of work by creators Burton Clarke, Lee Marrs, and Roberta Gregory in full colour.

Inside, readers are met with Cruse’s introductory editorial, and a four-panel newspaper-style strip by Melissa Bay Mathis, apparently originally created – per Mathis’ copyright notice – in 1979. An anthropomorphic examination of gender roles and expectations, Mathis features a male lion combing back his mane, hiding his masculinity, before meeting his friend, a lesbian, with fur blown out into a makeshift mane. It’s a simple gag, but may also – particularly for the time – offer a smidgeon of trans acknowledgement.

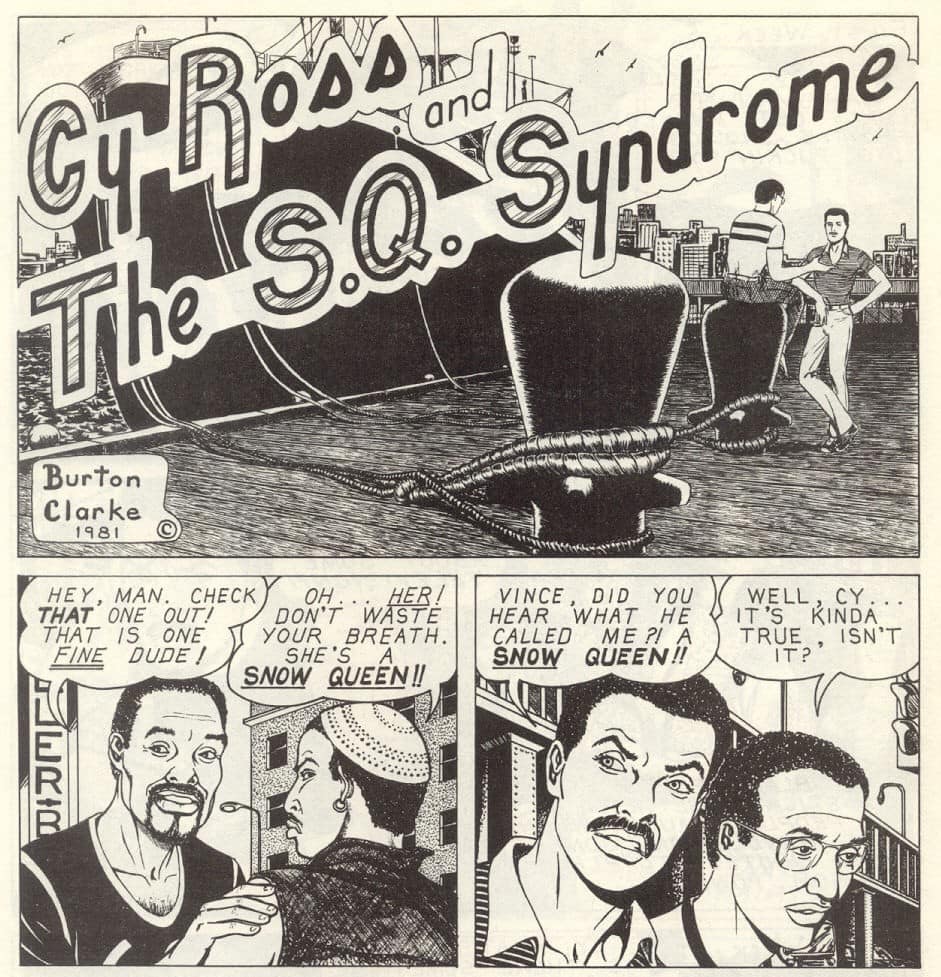

The headline strip of Gay Comix#2 is “Cy Ross and the S.Q. Syndrome”, by Burton Clarke. The five-pager focuses on the eponymous Cy, a black man accused of being a “snow queen” – that is, sexually attracted to white men – by his peers, including his friend Vince. What follows is a series of sexual misadventures as Cy tries to challenge the label, but fails to ‘seal the deal’ with any of the other black men he hooks up with. Worse, to him, he ends up so caught up in his burgeoning neuroses that he then struggles to perform when he goes back to white partners – all while his platonic friendship with Vince deteriorates.

Clarke’s strip is ultimately an exploration of both sexual racism and internalised racism, and offers no easy answers or solutions, either for the subject matter or the cast. It ends on something of a cliffhanger, in fact, essentially asking the audience to make their own minds up on Cy’s “S.Q Syndrome”. However, alongside the beautifully detailed artwork, evocative of the mainstream romance comics that once dominated the American comic book industry, Clarke’s work is still thought-provoking and challenging, 41 years later.

Jennifer Camper’s “She’s My Two-Timin’, Truck Drivin’ Mama” follows, offering a scrappier, edgier visual style that cements Gay Comix as still very much a product of the underground comics scene of the early 1980s. The strip is peak Americana with a lesbian twist, a story told as a country song, with the performer lamenting her on-again, off-again lover drifting in and out of her life only as she drives her big rig into town. It’s a tight three pages, capturing the loneliness and transience that can sometimes hallmark queer relationships, while also flipping some gender stereotypes – namely the idea of the wandering male trucker with a girl at every truck stop – on their heads.

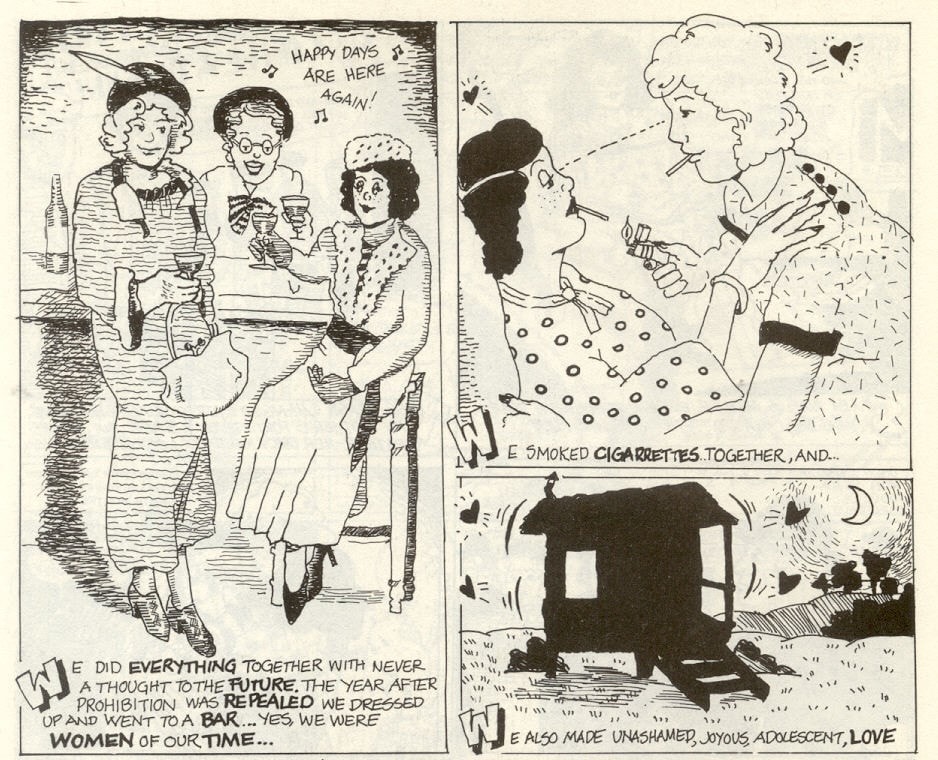

Mary Wings’ “Child Labor” takes readers back even further, to 1920s America and the cusp of the Great Depression for what might be the most resonant story of the issue. A young girl, adopted by a wealthy family shortly after birth, grows up in the lap of luxury, but finds her home life to be more of a gilded cage. Increasingly possessed of self-loathing at the perfect daughter role she has to play, the girl’s first and only solace comes from meeting Sara, two years older but seemingly a soulmate.

As the Great Depression bites, bankrupting Sara’s father and driving him to suicide, the girls start living together in secrecy, hiding a burgeoning relationship from the adults in their lives. Unfortunately, there’s no fairy tale romance to be had, as once she’s of age, the protagonist is forced to marry a man and “issue” a male heir in order to retain access to her adoptive family’s fortune. She picks Oscar, a man she presumes will be “preoccupied with business and politics”, hoping to continue her relationship with Sara in secret while he is otherwise occupied.

Sadly, that preoccupation with politics is her downfall. Forced to accompany Oscar to vapid dinner parties, she realises his worldview is antithetical to her own – extreme right-wing conservatism, blaming “Communists! And Jews… like your friend Sara!” for the country’s woes. Desperate for escape with her beloved Sara, the protagonist spirals ever deeper into regret, hating the compromises she’s felt forced to make her entire life, just to survive.

Throughout the six-page story, Wings weaves in literal background snippets of conservative radio, with disembodied voices talking about drains on the economy, threats to the fabric of society, the role of women, and more. It’s all presented as, and presumed to be, American broadcasts of the time – and terrifyingly, almost indistinguishable from the talking heads that could be heard on far-right news channels and podcasts today – but it’s only at the end that Wings twists the dagger, revealing every ‘broadcast’ to be a quote from Hitler.

Thankfully, the protagonist has the sense to abandon Oscar and escape with Sara, even if it means facing an uncertain future, but what will linger with the reader – perhaps more so now, in 2022, than in 1981 when the story was published – is how many themes of “Child Labor” are distressingly relevant again, almost a century on from the story’s setting. It’s a haunting, masterful piece of comic artistry.

Things get a little more light-hearted with the next strip, Joe Sinardi’s “Mallory, Duck With a Difference: Friday Again”. A mostly silent strip, it sees the gruff Mallory returning home from work and getting ready for a night out – trying on a host of stereotypically ‘gay’ outfits of the era – before finding the club is full of… chicken. It’s unclear if the intent is that the place is full of women – although the chickens are nearly all dressed with male-coded clothes – or that they’re somehow the cowardly type of chicken, but quite honestly, the joke doesn’t land, especially decades removed from publication and filtered through anthropomorphism. Still, Sinardi’s art is great, offering a two-pager in the vein of funny animal comics, and a perhaps a dash of inspiration from Steve Gerber’s and Val Mayerik’s Howard the Duck.

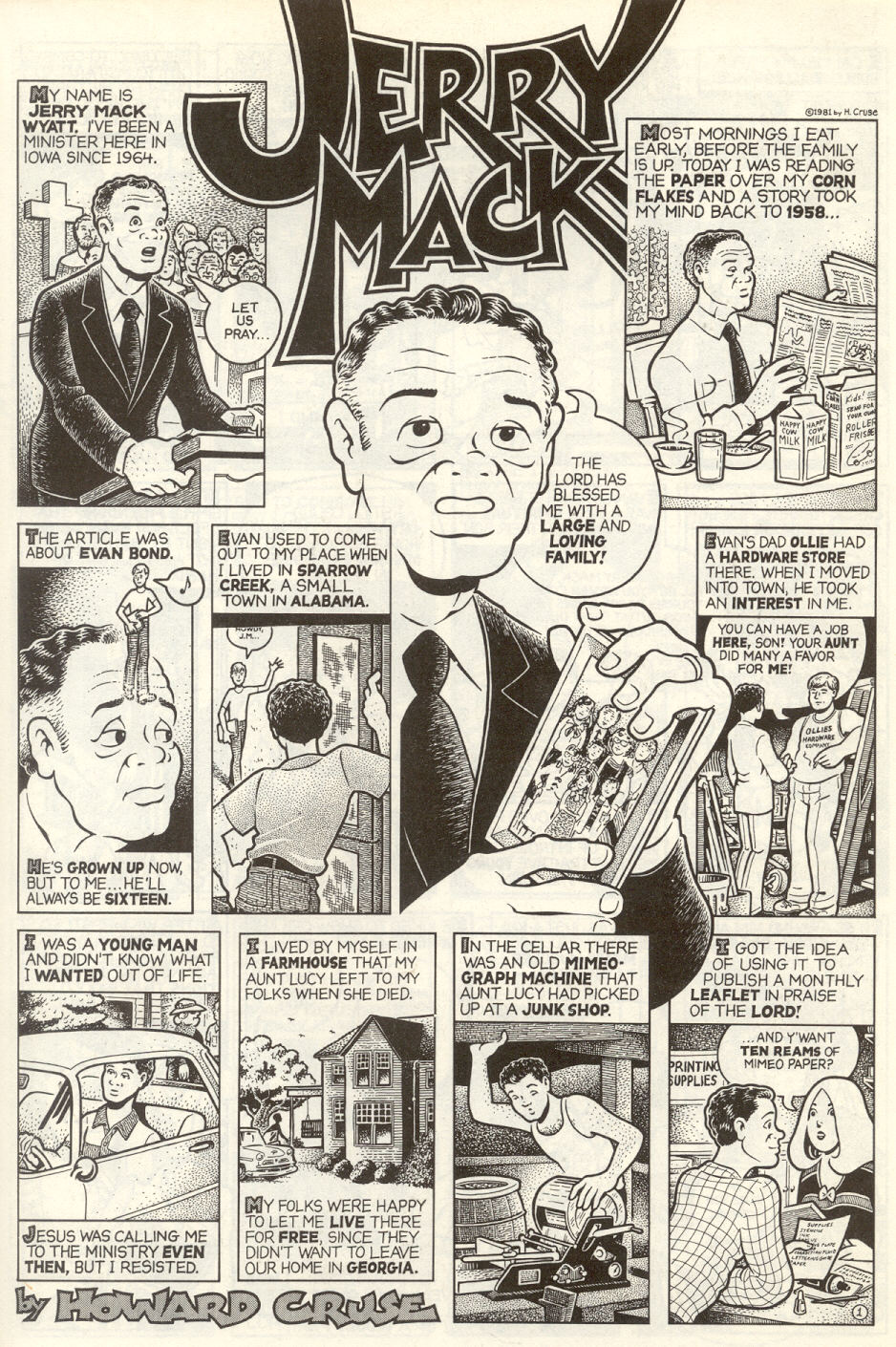

“Jerry Mack” is the first of two contributions Howard Cruse himself would make to the issue – the second being “Getting Domestic”, a one-page joke strip about the trials of living with a partner and negotiating chores – and is another poignant reflection on growing up gay in the American south. The epoymous Mack, now a pastor in Iowa, flashes back to his youth in Alabama, and his friendship with Evan Bond, the teenage son of a local family. Torn between his religious inclinations and the undeniable growing attraction he feels towards Evan, Jerry tries to ignore his homoerotic dreams about his friend, and even consoles Evan when he breaks up with his girlfriend.

However, things take a much darker turn when, trying to meet with Evan to discuss his deep conflict, Evan’s father Ollie shows up instead, along with the local pastor – and brutally beats Jerry, threatening to kill him if he doesn’t leave town. Jerry flees, joining seminary and marrying a woman, even having six children, but never truly forgetting his feelings for Evan.

Although not strictly autobiographical, the story draws on Cruse’s own background, and drips with criticism of religion and its adherents. As Ollie is beating Jerry, the pastor is more concerned with bad language and taking “the Lord’s name in vain” than he is with a young man being assaulted. When Ollie walks away, the pastor comforts him, not even looking back at the bloodied mess Jerry is left as. It’s a bitter and scathing commentary on the hypocrisy of supposedly loving Christians.

Yet the shame Ollie feels at the mere idea of his son being gay, or even the target of the affections of a “goddamned queer”, is also central to the strip. The Mack of the present day has lived a life in the closet, constantly telling himself he’s content, but never able to shake his own homosexual desires, or the shame he feels about it – shame that comes to the surface as he stumbles upon a news story about Evan, now a cartoonist, having come out as gay. It’s a fitting contrast with Cruse’s cover to the issue, with the character of Jerry Mack having effectively forced himself through conversion to live as his own idea of a respectable straight man, rather than allowing himself to live authentically.

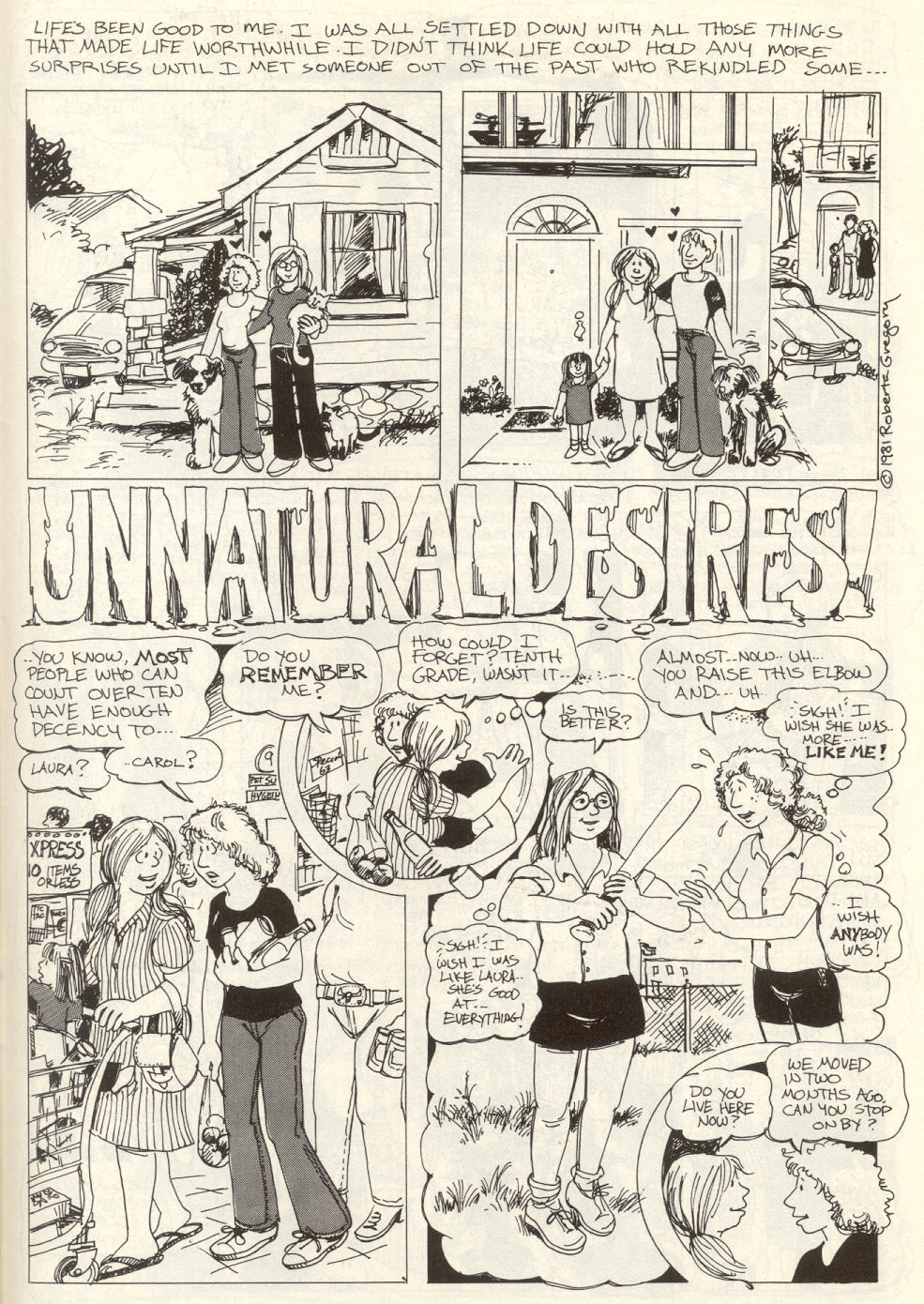

Roberta Gregory’s “Unnatural Desires” touches on another philosophical aspect of queer identity – the question of “how do you know if you haven’t tried it?” Gregory approaches the question from two perspectives – Carol, a woman seemingly happily married to a man, and Laura, ‘married’ – as much as was allowed in 1981 – to another woman. Crossing paths again after having not seen each other since high school, their catch up chat goes wrong when Carol realises Laura is a lesbian, reacting defensively to the idea that she might have been attracted to her in school.

The women challenge each other’s perspective on sexuality and identity, Laura suggesting Carol was too scared to try being with a woman in case she liked it, and Carol rebutting the same for Laura, who has never been with a man. Ultimately both women ‘experiment’ – Laura needing to get stoned to even be able to – and gain some better understanding of each other. The reader is left with the impression Carol is lying when she says she didn’t enjoy her tryst with a woman she met at a lesbian bar, but the story ends with the old friends reunited, albeit platonically. “Unnatural Desires” tackles identity issues that are sensitive even now, and handles them more brashly than would probably be seen today, but strip bristles with a sort of devil-may-care attitude that lends it energy to this day.

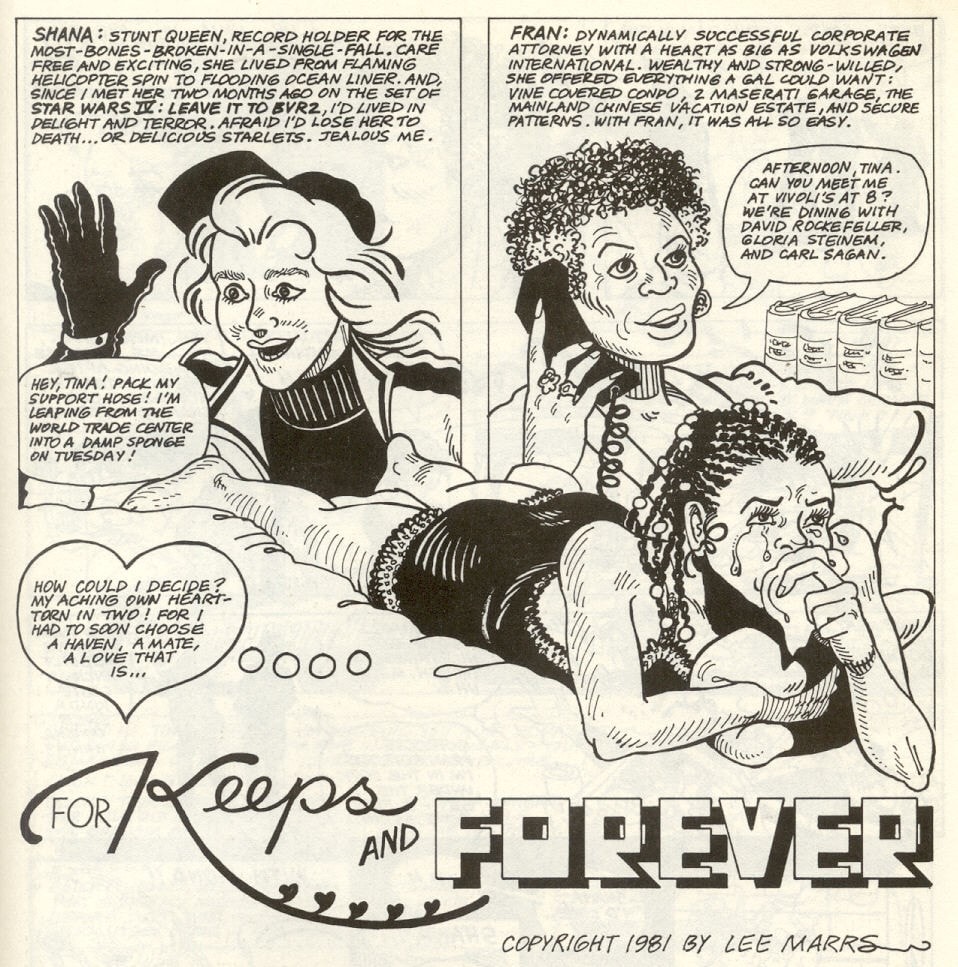

The issue rounds out with Lee Marrs’ “For Keeps and Forever”. Like Clarke’s opening strip, it taps into the visual language of romance comics, but Marrs leans into the melodrama of the genre a bit more. The focus is Tina, a young woman torn between her long-time girlfriend Shana, a stunt woman she met on the set of Star Wars IV: Leave It To BVR2 (a joke based on the 1950s sitcom Leave It to Beaver, that would have still probably been better than Rise of Skywalker), and Fran, a powerful lawyer who shows interest in her.

It’s a tale of jealousy and egocentrism, as the overly tearful Tina – Marrs masterfully parodying the weeping protagonists of mainstream romance comics – bounces between the two women, misinterpreting just about every interaction with both of them. It’s a genuinely funny comic, especially for those who get what Marrs is poking fun at, and all carried off with the creator’s trademark skill and charm. “For Keeps and Forever” also benefits from a final page in colour, as the story stretches around onto the back cover of the comic, printed on better paper stock and in full colour.

All told, Gay Comix #2 shows how rapidly the LGBTQ+ experience was changing in America at the dawn of the ’80s. Although a year between issues is glacially slow compared to mainstream comics, the gap brought in stories that began spotlighting the intersectionality of marginalized communities, with both Clarke’s and Marrs’ centered on gay black characters – a contrast to the all-white first issue. Being an underground comic, published without the oversight of censors, allowed the creators to tell stories that reflected the real lives of queer people of all stripes, all told fearlessly and with authenticity. It would be another year before the third issue arrived, but with its second issue, Gay Comix was already an important publication.

This article first appeared on our sister site, Gayming.