Meet the author: Gerard Cabrera

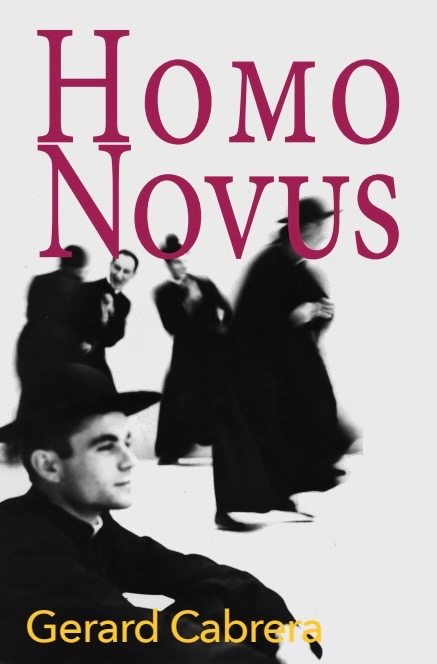

This year Gerard Cabrera is celebrating the publication of his debut novel Homo Novus, the story of a young man and the Catholic priest who seduced him when he was an adolescent.

Piety, compassion, lust, love… Feelings all the more potent when you are a Catholic priest confined to your hospital bed by an AIDS diagnosis, being comforted by the seminarian you sexually abused as an adolescent. It’s Holy Week 1987. The priest is Fr. Linus Fitzgerald, the young seminarian is Orlando Rosario. Both are shocked and shaken as they reflect on their desires and dreams, secrets and sins, hopes and faith, and the paths that brought them together. In Homo Novus, Gerard Cabrera illuminates with deep empathy and stark emotional honesty the journey these two men take separately and together — a journey that began with a violation of trust and leads them to places — sacred and profane — that they never imagined.

How did you choose the title of your novel?

Gerard Cabrera: The title was suggested to me by my friend, Philippe Masanet. In the Roman Republic, upon being elected to the Senate, you became homo novus, a new man. Only patrician males could become Senators at first, but when the office was extended to plebeian males, they, too, became new men. Saint Paul, who was a Roman citizen and familiar with Roman civic life, adapted and applied the term as a way to erase hierarchies among converts. In a sense, to establish a sense of equality among all new Christians. Of course, there is also a play on the use of “homo,” a slur for gay men that the characters all hope to transform into something new and more valuable.

Should I think of Homo Novus as a story about transformations?

Gerard: That’s a terrific question. Certainly the three main characters in Homo Novus wish to transform themselves. And at the heart of the Catholic mass is the act of transubstantiation, where the bread and wine become literally the body and blood of Jesus. Linus, who is from a white ethnic working class family, a mix of Irish and other European descent, wants to be an elite, and he wants to overcome his humble roots. The priesthood is a way for him to serve God but also gain social status and financial security. Orlando is a Puerto Rican kid from a poor family. Likewise, the allure of the priesthood for him is a way to achieve an American dream: success in the eyes of his family and community as well as a shield against racial and ethnic bigotry. Eric, on the other hand, is already an elite, and for him it is about climbing down from his unearned privilege, to become a hero for the dispossessed, with all the pitfalls and rewards that accompany his type of youthful downwardly mobility.

I sense you want to say more?

Gerard: Yes, you’re right, I do. Because there is more than class mobility at stake here. There is also the question of making yourself worthy of salvation. Linus seeks it through the mysteries of the priesthood. Orlando seeks it through giving himself to Linus, and Eric seeks it social activism. They do find hints of salvation, along the way, but only enough mystify them further. Linus can say the words that perform the consecration during the mass, but can’t figure out why he has committed terrible sins. Orlando has glimpses of the Kingdom of God while watching men in a bath house, but can’t tolerate house dust. Eric sees salvation in liberation theology, but can’t share with others unless he is the center of attention.

A recipe for trouble?

Gerard: Because in their attempt to overcome their fear of being cast out and condemned, Linus, Orlando, and Eric become entangled in increasing moral contradictions. They believe, but they deceive, too. They desire a life of honest service to others, but their first aim must always be self-preservation.

So they are hypocrites, in other words?

Gerard: Well, maybe so. However, I’d say it’s not their ‘fault’ they are so entangled and have to hide; they live in a deeply heterosexist world. I would also say their hypocrisy is enabled by their training as priests. A Catholic priest may be giving up a ‘normal life,’ yet it also sets him above and apart from others. You might start to feel as if ordinary boundaries don’t apply to you. It’s a mistaken belief with grave consequences, for Linus and Orlando especially.

But accountability is hard to find in Homo Novus, isn’t it?

Gerard: Judgment you can find everywhere — in the novel and in everyday life —just look around you. Accountability, not so much. For there to be accountability, there has to be transparency. And although there are rules and laws, for sure, in order to apply them with confidence you need facts. As the novel hopefully illustrates, in their hieratic world, facts are hard to find and what people are left with are surfaces, impressions, performances.

Speaking of performances, I noticed that you use a movie script format in certain sections?

Gerard: Linus likes movies and television in a way is that is almost reductively gay, and I have used the script format as the way he imagines his own life. Self-alienated, he stars in the safe theater of his imagination. Both in the sense that he sees these events as happening to someone else — perhaps this is self-protection — but also because he sees himself as larger than life, too. The nobody who becomes somebody everybody has come to see, as he puts it.

One thing we haven’t talked about is sex. Sexual violation, public sex, drunk sex, revenge sex. What was it like to write about it?

Gerard: First of all, Homo Novus is about the body as both means and ends — God’s body, the church as the head of the body of Christ, or the body that belongs to Linus, Orlando, or Eric. And so, what I wanted to convey most of all in the sex scenes was the sense of bodies in the moment: surprise, pain, violation, excitement and fulfillment, happiness, love. I wanted to describe the scene as plainly as possible from each character’s center. I felt that if I could do this, I would be doing enough — to watch them watch themselves and then describe their thoughts and feelings at the time.

Something I’ve also been wanting to ask is, why are there so few women characters in Homo Novus?

Gerard: The simple fact is that the world that makes priests is a man’s world. Women in Homo Novus represent the very narrow way the characters in the novel have been taught to view them. Store clerks will flirt with you, nurses take your temperature. Mothers hold families together, nuns pray for you and have secret intuition, and unmarried women with kids live on a tightrope. It’s a profoundly limited viewpoint, as we know, with damaging consequences.

We’ve been talking very seriously so far. Is there a place for humor in your book?

Gerard: Absolutely! Mainly, I use humor to distinguish between the private and the public lives of the characters. For Orlando and Eric, and even for Linus, gay bars, discos, and private house parties are the places for loose jokes and uncensored bitchy commentary. But in public, for example, Linus lightly mocks himself in a very rehearsed way for being a smoker, as if he’s told this joke dozens of times. In private anything goes. In public, it’s all about staying on message.

And you write in both English and Spanish. How did you approach this?

Gerard: That’s right. Homo Novus is written in English, Spanish, and even some Spanglish. I read a wonderful essay in Poetry Magazine, by Srikanth Reddy. He said something like this: English as a second language is my first language. I had never thought about it this way before, but it made so much sense. My parents grew up with Spanish in Puerto Rico, they then learned U.S. English. The first language I heard at home was their Spanish, but I also heard English as they learned it.

I’ve struggled in Homo Novus with using Spanish along with English. One of the self-doubts I have had to overcome is the prejudice, some internalized, that Spanish is not literary enough for a reader in English. This unfortunate attitude has really blocked a lot of creativity but I know every day there are more and more writers working with two languages at once, which makes me very happy.

And so, in Homo Novus, I tried to capture the diction of English as a second language, but also Spanish as it was learned by Puerto Ricans of a certain class and generation — the jíbaro Spanish I grew up hearing — and American English through the Puerto Rican ear.

For example, conversations between Orlando and his mother are in the family’s Spanish, and with his friend Angie and when in Puerto Rico he uses a more slangy Spanish or the Spanglish he’s accumulated through his own experience. Through all of this, the reader can inhabit with the characters their own languages. I know it can be challenging, but the reward is worth it.

About Gerard Cabrera

Gerard Cabrera’s fiction has appeared in numerous online and print literary journals. He has attended the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, The Writers Studio, and was awarded a Bread Loaf Camargo Foundation Fellow in Cassis, France. Gerard’s story “Disorder Under Heaven: The Situation is Excellent.” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize by Apricity Press (Issue 6) in 2021. Gerard earned a degree in English and American Literature at Brandeis University, his Masters’s Degree in Public Health from Hunter College, and his law degree from Northeastern University School of Law. Gerard is a Massarican from Springfield, Massachusetts, the birthplace of Dr. Seuss, Dr. Timothy Leary, Absorbine, Jr., basketball, and the first American dictionary. He lives and works in New York City.