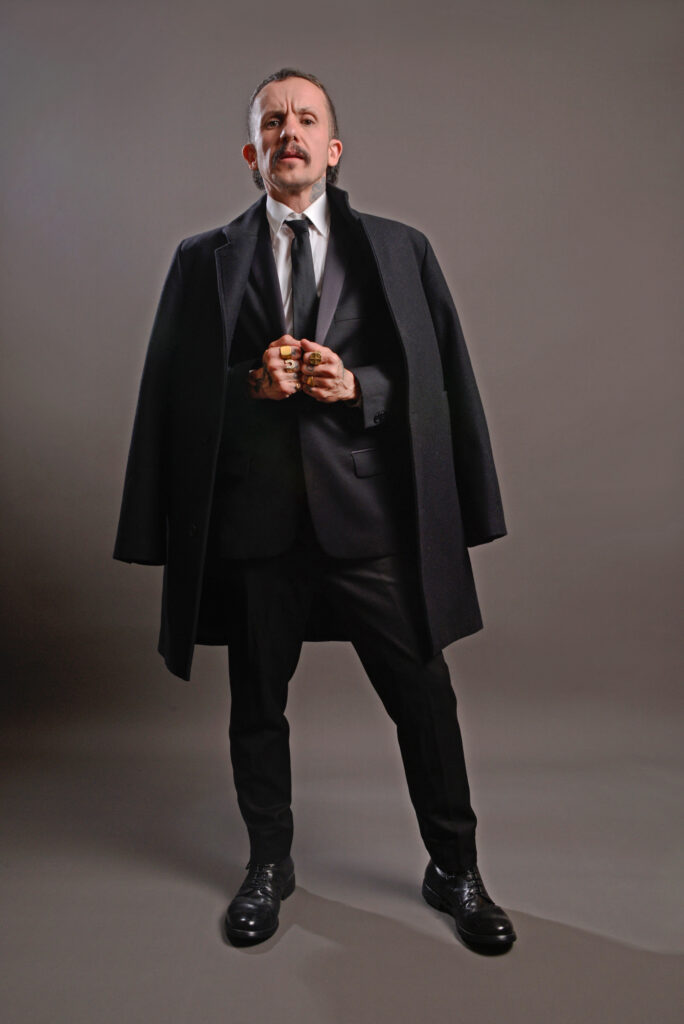

First out trans man signed to a major label releases best album yet

Lucas Silveira’s new album, The Goddamn Flowers, is his first record in nearly nine years and it may just be his best.

His last album — The Cliks’ Black Tie Elevator — was released in the fall of 2013. To offer some perspective — Barack Obama was still President at the time and no one knew what COVID was. On a personal level, Silveira had not yet had bottom surgery nor had he gone through the series of life-changing events that would inform his subsequent work.

For the uninitiated: Lucas Silveira came to prominence in the mid-2000s as leader of The Cliks, a Toronto-based trio. Their self-titled debut was released independently in 2004. Two years later, The Cliks were signed by Tommy Boy Records and Silveira became the first transgender male musician to ink a major label deal.

Snakehouse, their Tommy Boy debut, arrived in 2007 and was this writer’s introduction to the band. (It was also the start of my friendship with Silveira, which continues to this day.) Snakehouse was an excellent album: 10 songs of emotional, infectious rock and roll that featured the unforgettable single “Oh Yeah” and a gender-bending cover of Justin Timberlake’s “Cry Me A River.” That same lineup of The Cliks — Silveira on guitar and vocals, Jen Benton on bass and Morgan Doctor on drums — recorded their next effort, 2009’s Dirty King. By no means a bad album, Dirty King didn’t break much new ground musically. There were also interpersonal issues within the band and by the following year, the band had broken up. Black Tie Elevator, which arrived four years later, was a Cliks disc in name. But the musicians were different and so was the sound. There was still some rock, but the emphasis this time around was on soul, reggae and even baroque pop. And that was the last music Silveira released — until now.

The Goddamn Flowers, which arrived in July, is billed as “a complete departure from Silveira’s former work.” If anything, that’s an understatement; this is like listening to the work of a different person. And in a way, Silveira is a different person than he was nine years ago. Beyond the atrocities that we’ve all been through (from COVID to climate change to the nearly worldwide shift to right wing politics), Silveira has gone to Hell and back personally in the last nine years — more than once. Among other things, he has fully transitioned to male; he has been married and divorced; he has weathered the death of his father (to whom he was very close) and certain friends; he attempted suicide and experienced a subsequent spiritual awakening; he has struggled with alcoholism and addiction; and, most recently, he was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. Not surprisingly, many of these events influenced the material on Flowers. In fact, much of the album was written while he was in the throes of psychosis. Those hoping for a return to the rock and roll that Silveira was making in the late 2000s will have to keep hoping. But those willing to follow Silveira’s musical and personal evolution — or who simply appreciate beauty— will be richly rewarded.

There are 12 songs on Flowers, some written after the pandemic hit, others dating much further back. The album is extremely intimate, a song cycle composed on both guitar and piano. The lion’s share of the music was played either by Silveira or his co-producer, Jason LaPrade. Highlights range from the album opener “This Skin” to the the catchy, piano-based “Elyse” and from the eerie “Don’t Wanna Go Outside” to “Adega,” the short but uplifting closing track. (That last song contains the classic line, “I’m just a man who used to be a woman.”) References to insomnia, white rabbits and lost love pop up throughout Flowers. The album is meant to be listened to as a whole — not as a collection of singles or individual tracks.

Interviewing Silveira is different from interviewing anyone else. I have sometimes thought that he is the only man I know who’s more open than I am. Perhaps this is due to his having been a woman, perhaps not. But it’s a quality that I wish more people had. In his art and in his life, he holds little (if anything) back. So it’s hard not to admire Lucas Silveira as a person, beyond his obvious musical talent. This time around, we caught up by phone — me in New York City and him in Toronto.

The new album is The Goddamn Flowers. And as you told me before I heard it, it does sound like nothing you’ve ever done.

One thing in the press release was that many of these songs were written amidst a state of psychosis. That’s a strong word, you know? So I wanted to ask you to expand on that and for the layman — who in this case is me — what is schizoaffective disorder?

Lucas: Schizoaffective disorder is defined as the combination of major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. It’s hard to tell sometimes, when it comes to mental health stuff, when it started. I have what was considered substance induced schizophrenia. So it’s related to my alcohol use and also to the fact that I have a hereditary predisposition to schizophrenia — which I had no idea [about] until I went to get help and started doing research in my family. My Mom wouldn’t tell me anything. [She’s] Portuguese and she’s very protective and doesn’t like to talk about things like that. But through one of my aunts, I discovered that my grandmother on my dad’s side, and her sister, were both schizophrenic. Also, a cousin of mine a few years back [experienced] the same thing: substance induced schizophrenia. So with me, it was sort of a very insidious force.

What I’ve come to understand about schizophrenia [is that it’s] one of the most stigmatized mental illnesses that exists. There’s so little understanding of the illness, to the point where people think it’s a bunch of things that it’s not. Like the term “psychosis.” The term “psychosis” — all it means is a break from reality. It doesn’t mean that you’re seeing things, it doesn’t always mean you’re hearing voices… It just means that you have a skewed sense of reality or a break from reality. Also, schizophrenia is a spectrum. I thought you were schizophrenic or you weren’t, you heard voices or you didn’t; I didn’t realize there was an actual spectrum. Within that spectrum, there are different kinds and severities of schizophrenia. Mine is considered low spectrum; I land on the paranoid schizophrenic side of things with non-bizarre delusions. As opposed to bizarre delusions, which [would include] thinking aliens are putting thoughts in my head or the CIA is bugging my apartment. Those are considered bizarre delusions where it’s obvious that the person has a complete break from reality.

With me, it was called Persecutory Delusions, which are essentially things that could be real. [Things like] my friends are trying to harm me, my partner’s cheating on me — those kind of things. But this all got worse [during] the pandemic. It had sort of rooted itself before. But with the solitude [and] the increased drinking, it was kinda like my brain broke. So it became like obsessive-compulsive thoughts that I was certain were real, but weren’t. When I look back, pre-medication, and [consider] the logic of what I was thinking, I’m like, “How did I not know that that wasn’t real?” And the answer is always, “Because that’s schizophrenia. You don’t know. Your break from reality goes with your mental and emotional being.” Everything is in alignment to believe that all these things are true. Nobody can talk you out of it, even with evidence. And if somebody tries to, the first thought that comes into your head is, “They’re in on it. So I’m not talking to them anymore.”

Wow.

Lucas: Yeah. And you can be very functional with psychosis when you have the kind that I did. You can have a job, you can keep a clean an apartment, you can socialize. But what’s happening inside of you is all this massive chaos. So you kind of go into isolation because you end up thinking that everyone’s trying to hurt you. And the pandemic lent itself, ironically, to that. So it just brewed and brewed.

Then last summer, I wound up being attacked randomly on the street. I don’t know if you remember.

Yeah, I do!

Lucas: That’s what sort of tipped me overboard. I was already in a really bad place [and] suffering extremely. I had gone to a psychiatrist after friends told me that something was wrong. And I was told that [I had] alcoholic psychosis and a bunch of other things that weren’t factual; schizophrenia can be hard to diagnose. So with me, it was a long process until that night happened. The next morning, I was like, “I’ve lost time. I don’t know what’s going on. I have a dog, I don’t want to hurt her.” I never have, but that’s where my brain was going. Like, if I don’t get help, something bad’s gonna happen.

So I committed myself to a mental health facility here in Toronto called CAMH, which is the Center for Addiction and Mental Health. And I got the help I needed there. I was finally diagnosed, I was finally told what I had to do to get better. It kind of felt like Hell on earth. [That’s] the only way I can explain it. A lot of people around me kind of split because, to them, it looked like bad behavior. When in fact it was just me believing that they were horrible people and were trying to hurt me. At some point, I used to think some of the people were actually trying to kill me… It was pretty horrifying.

It sounds scary as Hell. [And] it sounds like it can lead to sort of a vicious circle. I would think the more paranoid [you are, the less] people wanna hang with you. And then you get even more paranoid, right?

Lucas: (Laughs) Exactly! And then I”m like, “See?! They’re in on it.” So I did get diagnosed and I told some of the people in my life that it was happening. Then I went on medication. I’m on anti-psychotics for the rest of my life. And they work! It took about two and a half to three months for them to sort of kick in and for me to stop having delusions. But when I say a lot of [this album] was written in psychosis, it was. I wasn’t one of those schizophrenics that goes out on the street and is walking around, yelling at things that aren’t there. I was one of those schizophrenics who was quite functional. So I wrote about the stuff that I was feeling and [that] I thought was real.

Can I ask you about a few of the specific songs on the album?

Lucas: Absolutely.

The two that really stood out as being pandemic informed were “Isolation Lullaby” and “Don’t Wanna Go Outside.” Especially “Don’t Wanna Go Outside”! The lines about the seasons changing and [how] you might walk to the corner… Aside from New Zealand, I think [COVID] has affected [everyone]. Tell me a little about how the pandemic informed some of the lyrics on this record.

Lucas: Well, the interesting thing about “Don’t Wanna Go Outside” is that I didn’t write it during the pandemic; I wrote that song about nine years ago.

Wow!

Lucas: Yeah! It was related to me being agoraphobic. When I used to get really depressed or have a lot of anxiety or have something going on in my life that I just could not cope with emotionally, it became extremely difficult for me to walk out my door. That started when I was around 21 [or] 22, when I had a mental breakdown. I became unable to work, I was living with my parents, they had to [change] their retirement plans because they needed to take care of me. For three years, I was a complete mess. I went on anti-depressants — and back then, anti-depressants were ridiculous. I’m about to be 49, so this is over 20 years ago.

So I remember the first time I went outside and experienced agoraphobia, because I had never experienced it before. I literally went to a gas station that was up the street to buy a pack of cigarettes. And I got probably about 50 feet from my front door — and my legs started collapsing. I actually had a physical sensation to the outside. Everything started narrowing in. I felt like I was in this tube and like I was gonna pass out — and I had to crawl back home. And I didn’t realize what was happening; back then, there were no conversations around panic attacks and anxiety. Nobody talked about mental health! It was like, “Something’s wrong with this person. Don’t talk about it. Put them in the hospital and don’t tell the rest of the family.” Everything was very shameful and you were considered weak if you went on anti-depressants.

So that was the first time I experienced it. And then [about] nine years ago, I started experiencing it a lot. That’s when I wrote this song. I wanted to put it on the last Cliks album, Black Tie Elevator, but it did not fit at all! It didn’t feel like it belonged. Then when the pandemic happened, I was like, “This is the perfect moment for this.” Because not only did I experience this my entire life, I am experiencing it right now. So it really belonged on this album.

And when it comes to “Isolation Lullaby,” that song [was] written a couple of weeks into the original quarantine. I wrote it for my ex-girlfriend because we weren’t living together. And obviously, everybody was horrified about what was happening. We were all scared. I just wanted to write her a lullaby to help her fall asleep and feel better and to know that I was there to protect her, even if I was far away. So yeah. That ended up being this cute little love song. But again, it was one of those experiences where I didn’t even know where it came from. [That’s true of] a lot of the songs on this album. All I know is I started to play the piano a lot more and [I was] writing a lot more from the piano. It’s a spiritual thing, songwriting. It comes from somewhere I don’t understand but I just kind of follow its lead.

I know that you also made a trip back to Portugal not long ago. And listening to the last song on your album, “Adega” — was that written in in Portugal?

Lucas: It was. So “Adega” — the translation in English means “wine house.” But what it is literally, is a cottage. Traditionally, it’s very interesting…. When you think of somebody having a cottage on an island, it’s like here’s your house and 15 minutes away is your cottage. The purpose originally was for it to be a little house in the middle of a grape field, where they would pick grapes [and] then they would make the wine. So now, anything that’s like a little house that’s close to the ocean is considered a cottage. My place — you can’t make wine in it but it’s basically [an] adega.

My Mom and Dad — before my Dad passed, [he] was obsessed with the idea that I could own my own home. My brother did, my sister did. But he literally thought that I was gonna become homeless. He said he could die with that in his mind [so] he wanted to get me a place. And I said, “Dad. You’re 70. Give it up! I’m fine. Rest, do your thing. I”m probably never gonna come here anyway and if I do, I can stay at our house.” But he and my Mom were like, “Nope! We’re gonna do this.”

So they bought me this little property and renovated it completely. It’s just a little, teeny cottage [but] every time I go there, it’s like a part of me — the anxious part of me, the kid that used to live there that was tortured, everything negative that I feel inside of myself — just goes away. And that particular song was essentially written about the present of where I was. When I talk about lizards and rocks and trees — just being on my balcony, looking at the ocean, listening to the wind — everything landed in the ocean. And the only thing I had that was causing me any kind of disconnect was that I was in love with [somebody] who was far away from me. We were having some problems. So I was like, “I have to be rooted in all of it.” And I was sort of inviting her to be with me. That’s what that song is about.

I wanted to ask you just a couple of other non-album things before I let you go… I asked you this once before but being that Paul McCartney turned 80 last month, to me that’s a cause for celebration.

Lucas: God, yeah!

Just [tell me your] thoughts on McCartney, The Beatles and what they mean to you.

Lucas: They saved my life. It’s that simple.

I remember when I was little, any time I [was in] pain, I could just go and sit in front of my sister’s boombox. I would grab this tape — a Beatles greatest hits tape. This would have been around 1976 [or] ’77. And it was like leaving the world when I listened to The Beatles. I would close my eyes, I would sit on the floor and I would just let my imagination flow, being dictated by the lyrics and melodies of The Beatles. I truly believe they were my teachers when it comes to being a songwriter. Everything that I do in my songwriting, that was the root. I remember the first time I heard “Eleanor Rigby.” It was such a dark song, you know? To a kid, I was like, ‘This is kinda spooky.” It was so different from things like “I Wanna Hold Your Hand,” which was very poppy. So there was a trajectory of the songwriting from the ‘60s to when they stopped being a band.

If you could give a message to young people — college aged people who are struggling either with being trans or, more broadly, [with] mental health issues — what would it be? And if I’m putting you on the spot, just tell me.

Lucas: Oh no! Totally cool. I completely think that these are important things to talk about. And the reason I think they’re important things to talk about is because nobody does! That’s one of the [problems].

When you have mental health issues, it feels so incredibly lonely. You have all this stigma around it and people who will believe anything that mainstream media tells them. For example, a lot of people believe that schizophrenia is multiple personality disorder. It’s not; there’s nothing about it that’s multiple personality based. So when it comes to younger folks who are feeling these things, it’s the same thing. I always tell people who are trans, who are gay, who have something going on inside them that they’re afraid to talk about. The first thing is, find a safe space. Find a person that you feel safe around, who you know is not gonna judge you, who is not gonna betray your confidence. Find a group — you know, like a LGBT group or a trans group. And find ways to be part of it safely, to get the kind of support that you need. There are a lot of places that will help people on a confidential basis because they do know the stigma that exists.

Here in Canada, when I admitted myself, it was completely covered. It was all free. [But] even though it’s accessible here, and I feel so lucky, there was still a part of my diagnosis that was very cis, heterosexual normative. So I had to go out of my way to find help that was more queer-oriented. And luckily, I ended up finding help. It does exist. So I always tell people: if there’s a community somewhere — like a trans men’s group, a non-binary group — sometimes it’s through those places and finding people who are like-minded and feel safe to you, that’s sort of where your healing begins. Because when we don’t feel safe, we can’t heal.

It’s connection, you know? Connection through like-minded people who are safe.

Follow Lucas Silveira on Instagram here.

Get the new album by Lucas Silveira here.

Lucas Silveira Upcoming Gigs

10/04/22 – Toronto @ Bovine

10/05/22 – Ottawa @ Avant-Garde

10/06/22 – Quebec City @ Source de la Martinieré

10/07/22 – Montreal @ Turbo Haus

10/09/22 – Hamilton @ Mill’s Hardware