Our brothers’ keepers: Michelangelo Signorile on gay men’s health

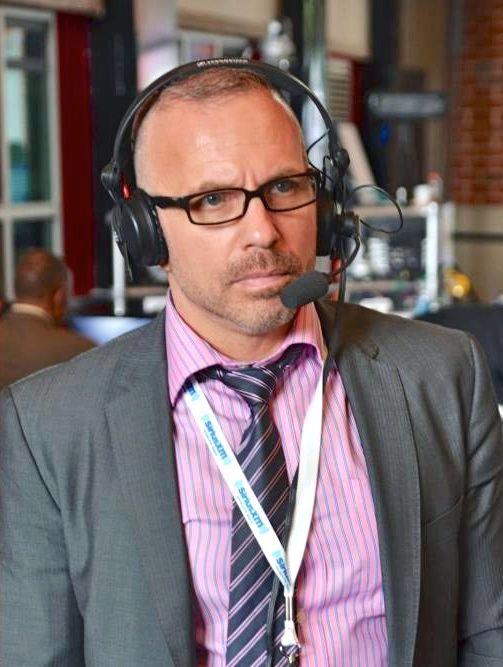

Michelangelo Signorile is first and foremost an activist. He wants his queer and trans community to live their best lives—it’s something he has been fighting for since the 1980s when he joined ACT UP and co-founded Queer Nation and co-founded the iconic OutWeek magazine.

Signorile, author of It’s Not Over, believes that GBT/MSM men need to “be each other’s keeper” and help each other stay safe and alive and well.

The AIDS crisis in the U.S. redefined healthcare for gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men as trauma-based emergency care. Prior to the current range of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) drugs, an HIV diagnosis, with full-blown AIDS the next phase, was often a death sentence. But in this era of PrEP, are gay, bi, and trans men, and men who have sex with men (MSM), getting appropriate healthcare for their non-HIV needs?

The recent mpox outbreak suggests that healthcare for GBT men and MSM is still limited to crisis management and that stigmas attach to this group of men that do not attach to cis-het men. Everyone failed men with mpox—including the federal government. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), was slow to respond to the needs of the GBT community during the height of the outbreak last year.

Michelangelo Signorile has been one of the best-known queer journalists and gay activists in the U.S. for decades. Signorile became a gay activist in 1988, after attending an early meeting of the iconic AIDS activist group ACT UP. He was soon chair of the media committee of ACT UP. Signorile was also a co-founder, along with three other ACT UP members, of the activist group Queer Nation.

His 1993 book Queer in America: Sex, The Media, and the Closets of Power jettisoned him from co-founding editor of the groundbreaking OutWeek magazine to mainstream media.

In May 2017, Signorile took on Donald Trump and Republican legislators in a Huffington Post story. He wrote that no Republican congressman “should be able to sit down for a nice, quiet lunch or dinner in a Washington, DC eatery or even in their own homes”, and “should be hounded by protestors everywhere, especially in public ? in restaurants, in shopping centers, in their districts, and yes, on the public property outside their homes and apartments.”

As host of the Michelangelo Signorile Show on SiriusXM every day from 3pm to 6pm, Signorile is the only national queer voice in the country that people are listening to daily.

In an interview with Queer Forty, Signorile spoke declaratively about gay men’s health and how his personal activist history made it essential to talk about his recent prostate cancer diagnosis. Signorile addressed how the healthcare needs of GBT/MSM men are not being addressed, either within the community or mainstream culture. Signorile expressed his concerns about educating men on various threats to their health, including, but not limited to HIV and healthcare access.

Gay, bisexual and trans men and men who have sex with men (MSM) are at constant risk of a plethora of avoidable and controllable health issues, including heart disease, diabetes and cancer.

Studies show that preventative care is a life-saver for men and that even small changes in lifestyle can increase both life expectancy for men and quality of life—making regular healthcare essential to good health.

Yet despite myriad advances in medical science and available treatment protocols, men live sicker lives and die younger than women, on average by over five years.

More babies assigned male at birth are born every year, but by as early as age 35, women outnumber men demographically. This gap only widens with age: 57% of all those ages 65 and older are female; 65% of people over age 80 are women.

A main reason is women are twice as likely to get preventative health care. Men not getting necessary preventive care leads to missed opportunities for early detection and treatment for a range of conditions, including the top two causes of death for men: cardiovascular disease and cancer.

But GBT and MSM are still being compartmentalized by their sexual orientation by the U.S. healthcare system. The CDC leads with STIs as their main concern for “gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.” CDC says, “For all men, heart disease and cancer are the leading causes of death. However, compared to other men, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men are additionally affected by: Higher rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs); tobacco and drug use; depression.”

Signorile says, “Cisgender men in general in our society often don’t pay attention to their health, or get regular screenings. A lot of it is tied in with a kind of macho bravado and fear of finding weakness—including physical weakness.”

But Signorile says that “even when there is attention and education on men’s health it’s overwhelmingly geared toward straight men. So we need to be talking to gay men, bi men, and in the case of prostate cancer, trans women, not only about the importance of early detection but about their own needs, and the way health care issues affect people uniquely regarding their sexual and social lives.”

The details matter, says Signorile, even if it feel like a lot. “I believe we also need to be talking to men who have sex with men about treatment and that’s why I get a bit detailed about it—because I think most people only learn about treatment when faced with cancer. This prevents them from getting screened, out of fear, because they have outdated information on treatment or see sensationalized stories online. They believe all treatments are harsh and difficult. And today, at least with prostate cancer, early detection means leading a normal life and beating cancer, after a relatively non-invasive treatment. If you find out after it has progressed further, however, it gets complicated.”

Gay and bisexual men also need to educate one another, Signorile says, “and be one another’s keepers—since society on the whole is not doing so. Doctors and even major medical and cancer groups are all over the map, for example, about what age people with prostates should begin PSA testing. In our friendship networks we need to gently prod one another about testing and about treatment. One of the silver-linings of monkeypox was that queer men were actually talking to one another about health issues and sexuality openly, and exchanging information on the vaccine, where to get it, and so forth. And there was a subtle peer pressure to get the vaccine. People saw it as a community responsibility and rose to the challenge.”

The lack of discourse on GBT/MSM health has real life consequences, Signorile says.

“Believe it or not, two gay men in my life, in my age group—people who lived through the worst part of the AIDS epidemic—in the past two years, on two different continents, developed full-blown AIDS. One of them died. This is shocking. These are educated men. But neither was on PrEP nor testing for HIV over many years. How is that possible?”

He thinks “much of it is about fear—something may have happened, an unsafe incident in the far past–and they just didn’t want to know, even with the life-saving treatments we have. I think about what I could have done as a friend, and it brings me back to being a friend’s keeper. Maybe if I talked more about testing for HIV regularly, and asked these friends about it, it might have jarred something, causing a conversation. I just assumed my friends were testing and taking care of themselves. But no more. I have conversations.”

Signorile, now 62, was diagnosed with prostate cancer in September of 2021 at the age of 60 after several months of tests. “I went for my annual physical and it turned out my levels of PSA—prostate-specific antigen—were slightly-elevated.”

He explained, “That is a number determined via a routine blood test, which the Prostate Cancer Foundation recommends that anyone with a prostate get annually beginning at 45, and at 40 if they are Black. I had no symptoms of prostate cancer—no pain or urinary issues—which is quite common. So getting PSA-tested is important. Even a physical exam—digital rectal exam—showed nothing out of the ordinary.”

Signorile’s next step was to see a urologist, but the specialist “found nothing of concern in a physical exam, and even a sonogram which he performed appeared normal.”

PSA can spike for a variety of reasons, including from a urinary tract infection or even from riding a bike. Signorile was monitored every three months, but the PSA number only went higher.

“That’s when I got the biopsy in my doctor’s office,” Signorile said. “I should have been able to get an MRI first, to rule out a tumor—but my insurance wouldn’t pay for it because everything except the slightly-elevated PSA was normal. So, I wasn’t sick enough to find out how sick I was—one of the main problems with insurance in this country! The biopsy, for me, was quick and not painful. In the urologist’s office, local anesthesia. Just some pressure, done in 15 minutes.”

The next two weeks as Signorile waited for the biopsy results to come back were “among the worst two weeks of anxiety I’ve ever had. And then when the doctor called with the news, my heart sank.”

Signorile said, “I was terrified my life was going to dramatically change, only having read some of the worst-case scenarios online. But I felt almost 100% better after my husband David and I went to my urologist. He explained it was found early and showed us precisely where it was limited to in the prostate.”

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in American men, except for skin cancers. All men are at risk for prostate cancer and 13 out of 100 American will get prostate cancer during their lifetime. Black men and men with a family history of prostate cancer are at increased risk for getting or dying from prostate cancer.

A CT scan and a whole-body bone scan showed that Signorile’s cancer had not spread beyond the prostate. This meant he might be a candidate for active surveillance, which is now a standard of care for low-grade prostate cancer. Most prostate cancers grow very slowly, though there are aggressive cancers, and genomic testing can determine that.

In an active surveillance program, PSA tests are done every few months, with more biopsies over time. As Signorile told Queer Forty, “You may never need any further treatment, as the cancer may never progress.”

Treatments include surgery to remove the prostate and surrounding areas, including lymph nodes and seminal vesicles, or radiation. Either choice may also include androgen-deprivation therapy, depending on how advanced the cancer is.

After a lot of research, Signorile decided “surgery, a radical prostatectomy, was definitely not for me. And today it really is a choice, a matter of preference, as long-term studies show equal outcomes with surgery and radiation.”

Signorile said, “The side effects of surgery, both short-term and possibly long-term, are greater, regarding both sexual function and urinary issues. Straight men, gay and bisexual men and transgender women have very different priorities and sexual realities.”

Signorile said this is where who one’s clinician is matters. “All of my doctors are gay or certainly know I am, which I think is very important. I consulted gay patient advocates and went online to HealthUnlocked to the prostate cancer threads and forums and one in particular for “Prostate Cancer and Gay Men.” One piece I suggest every gay and bisexual man read is Gay Men Should *Never* Get a Prostatectomy by respected patient advocate Allen Edel, whose site is also a wealth of information and links to important data and studies.”

The next couple months included consultations at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City where Signorile lives and which has pioneered treatments for prostate cancer. With a faster-growing cancer, Signorile was not a good candidate for active surveillance and consulted a radiation oncologist.

Amazed by how “relatively non-invasive all the therapies are, and how little time they take,” Signorile detailed what he learned in his newsletter on Substack, as well as the option he chose.

In January of 2022, five months after his diagnosis, Signorile underwent low-dose brachytherapy in which radioactive seeds are implanted—minimally invasive out-patient procedure with a success rate of well over 90%. “You’re in and out within a day,” said Signorile.

He said, “Radiation has short-term and possible long term effects too, including affecting urinary and sexual function, even if more minimally than surgery. But I’m lucky that I’ve had no side effects, even the short-term urinary frequency that is common. So I feel good about that.”

Queer Forty wanted to know why Signorile decided to go public with his diagnosis when so many men either choose not to or wait years before disclosing?

He said, “My entire life as a queer activist and journalist, and certainly as an AIDS activist, has been about being open and using my own experience to help inform others. There was no way I could not be public about it. I knew that I could inform many, as I had so many fears myself that dissipated once I learned about prostate cancer and about treatments—and I considered myself relatively informed—so going public was something I knew would do a world of good in getting people to get tested and treated, and overcome fears. Cancer, and treatments for it, need to be demystified.”

Queer Forty talked to Signorile about men being wary of having a rectal exam and how that wariness is about fear and homophobia. Men don’t want to talk about asses, he said.

“A digital rectal exam is a doctor using one finger, gently, for about four to five seconds,” said Signorile. “That’s it. It boggles the mind that men are afraid of this—and that even many doctors don’t perform it—but this is all tied in with homophobia, particularly among straight men and straight doctors. You need to have it done. Sometimes a DRE shows something when the PSA test doesn’t. And sometimes the PSA test shows something, as in my case, when the DRE doesn’t. You need both.”

The activist Signorile, the brother’s keeper Signorile, is adamant that men need to fight for their own healthcare. “If a doctor won’t do it, you need to get another doctor. Some of them will say, ‘Oh, it’s unnecessary, the PSA test is enough.’ Tell them no thank you. Honestly, there are also doctors who don’t do PSA tests unless requested—and even then, will sometimes dissuade people. There’s some resistance in the medical community because of the fear of too many unnecessary biopsies and over-treatment. While that’s a real concern, it doesn’t mean you throw out the PSA test. Or the DRE. You have to be your own advocate. Do the research and demand screening.”

Health insurance remains a factor for gay men and plays a role in men getting treatment and care, as Queer Forty has reported recently here and here.

“As I noted in the first piece I wrote about diagnosis,” Signorile said, “I consider myself very privileged having comparatively good health insurance via my employer, headaches and ridiculousness notwithstanding. It means very little to tell people to get PSA-tested if they are uninsured and don’t have adequate medical care. And that is the case for millions of Americans and, disproportionately, LGBTQ people and people of color.”

Signorile said his diagnosis “reconfirmed my commitment as an activist and journalist to fight for access to health care for everyone. We have to keep this at the forefront. It absolutely hinders a lot of people, because even if the resources are available, they just don’t know where to go. So, as we fight for universal health care, it’s also up to all of us to educate and make sure people who are uninsured know about community health clinics, LGBTQ centers and other places where they can get the health care they need and the consultations that are vital.”

We must, Signorile says, “be our brothers’ keepers.”