New look at the work of gay photographer George Platt Lynes

In the 1930s and ’40s, George Platt Lynes was one of the best-known photographers in New York City. His portraits and fashion photographs were published in such national magazines as Town & Country, Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar.

Today, Platt Lynes is best remembered for a vast archive of male nude photography that has since the 1970s been increasingly “rediscovered” by a new generation of queer artists and curators.

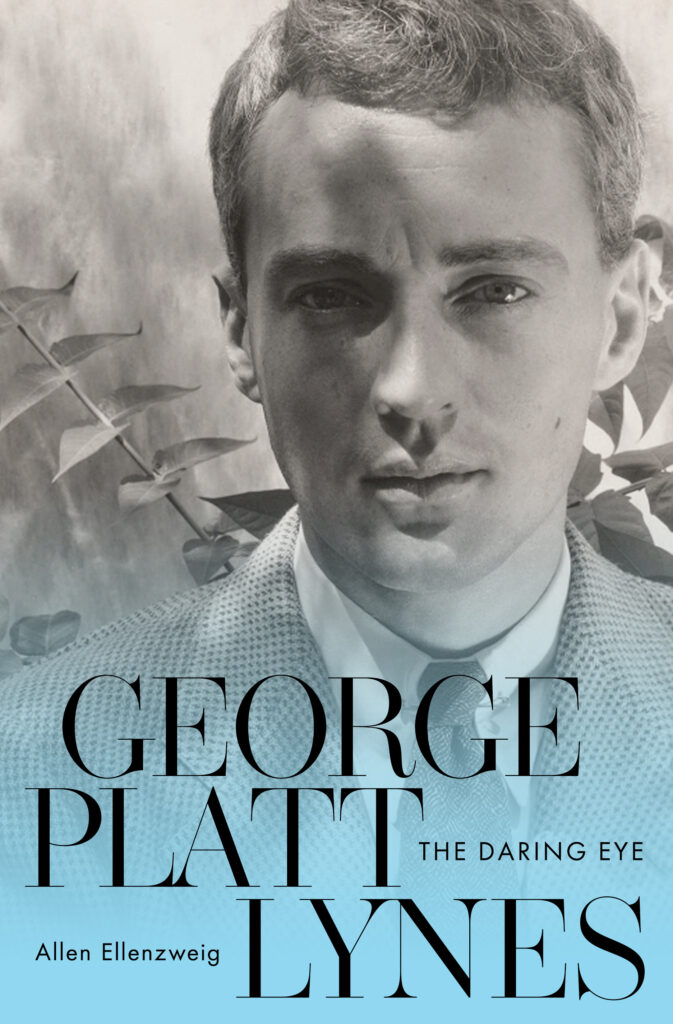

Over seventy years after Lynes’ death at the age of 48, Allen Ellenzweig has written the first book-length biography of the artist, George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye. Ellenzweig, who is also the author of The Homoerotic Photograph: Male Images from Durieu/Delacroix to Mapplethorpe (1992), offers a richly researched portrait of the circle of artists and writers who created a queer, cosmopolitan world in mid-century America.

James Polchin: So who was George Platt Lynes, and what motivated you to research and write his biography?

Allen Ellenzweig: Lynes was a photographer whose portraits were of leading writers, artists, and classical dancers—and, quite significantly, the nude figure, especially the male nude. From the start, he set his sights on photographing prominent writers in English and French who dared to deal with sexual activities. Jean Cocteau, Colette, André Gide, and the expatriate American writer Gertrude Stein were early subjects for his camera. Stein became his most important mentor in his early years when, briefly studying in Paris to prepare for entry into Yale, he imagined he would make his living as a man of letters. While he eventually made his living as a fashion photographer in the Condé Nast publishing empire, the male nude photographs were an obsession without commercial recompense. They were too frank for American publications and forbidden transport by the U.S. Post Office. However, when social mores and obscenity statutes relaxed, this work was exhibited and then published. Lynes’ work with the male nude has influenced gay photographers of the post-Stonewall generation—men like Robert Mapplethorpe, Herb Ritts, and Duane Michals.

I ultimately wrote his biography because, when I was younger, I was an incorrigible Francophile. I learned to speak French (passably well) because of that. But lest anyone think I was reading Derrida, Lacan, and Foucault—no, no. I wanted to live in the Paris of Audrey Hepburn’s Funny Face and the France of Two for the Road. Lynes participated in the Paris of the 1920s. In some sense, Lynes, ripening sexually and socially in Paris and in the South of France, lived the kind of cosmopolitan life I wished to lead. And, of course, I was passionate about photography and the homoerotic image. I’d written on Lynes’ work already. So, it seemed a perfect fit.

JP: You detail so well Lynes’ time in Paris, including his presence in Gertrude Stein’s circle when he was barely eighteen years old. How important was Paris and that expat world of the late 1920s to Lynes’ creative education?

AE: The expatriate world of post-World War I Paris was crucial to Lynes’ creative and social education, for through the Stein salon and her extended circle he met a wide range of Anglophone literati—not only the writers of the period, but small press publishers and editors like Ford Madox Ford and important booksellers like Sylvia Beach, whose Shakespeare & Company became a model for Lynes when he opened a bookshop back in Englewood, New Jersey. He also entered into Stein’s salon at a crucial period when many of her acolytes were, like Lynes, gay men who formed her “seconde famille” and sought her counsel and approval. The entirety of cosmopolitan Paris was also his classroom as he experienced its nightlife—the café Styx and Le Boeuf sür le Toit and La Revue Nègre, which was a showcase for African-American musicians and entertainers. As a charming and quite handsome young man, he was taken up by other gay men, including the Surrealist poet René Crevel who was a favored member of Stein’s coterie.

In all, I think it safe to say that he was not there merely for the breadth of cultural experience available, but for the chance to taste a quality of libertine life unavailable at home in America. Lynes, like the others, settled into the City of Light as “sexpatriates,” if I may coin a phrase. Paris made George Platt Lynes a cosmopolitan—sophisticated, with discerning taste.

JP: I love the term “sexpatriates”! No doubt it will soon go viral. On that subject, in the book there’s a keen sense that Lynes was both aware of and open about his homosexuality from a fairly young age, and seemed not at all shy about expressing it to his friends and family. He was directly honest about his sexuality with his father, an Episcopal minister. For a number of years in the 1920s and ’30s, as he was building his photography career, he maintained a ménage-à-trois with the writer Glenway Wescott and the publisher Monroe Wheeler. What does Lynes’ story tell us about how he and other gay men in his circle navigated their public and private intimacies in those decades before the idea of “coming out”?

AE: Lynes’ younger brother Russell wrote that if asked when George “came out,” he replied that his brother was never “in” the closet. This is true, but within limits. Lynes and his intersecting circle of cultural producers on the transatlantic scene—artists, writers, scenic designers, dancers, musicians—formed a loose community of sexually sophisticated urbanites living in Paris, London, the South of France, and New York. There was a good deal of cross-pollination among them, especially when they came together on large artistic endeavors like the Gertrude Stein-Virgil Thomson opera Four Saints in Three Acts. Stein and Thomson were Americans, but Stein was based in Paris. The English choreographer Frederick Ashton, like Thomson a gay man, was enlisted to direct the large chorus of singers and dancers, who, it turned out, were all African-Americans. Ashton recruited the dancers from Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom. Some may have been gay or on the “down low.” (I don’t know if that expression was even current at the time.)

All this is to suggest that this international cultural community was a tolerant cocoon within which sexual marginals of all types labored without fear of “discovery.” Yet even within the tolerant precincts of cosmopolitan cultural capitals—and certainly at salons like those of Muriel Draper and the Kirk and Constance Askew “teas” on the East Side—rules of comportment went unspoken but enforced. As Virgil Thomson is reported to have said, you did not “camp” at the Askews, although gay men, sometimes in couples, were invited as guests. Lincoln Kirstein [impresario and cofounder of the New York City Ballet] claimed that everybody knew what everybody was up to, but a kind of “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy obtained. According to him, this was not a subject for “gossip.” To me, the interesting conclusion is that: a) not everyone was in the closet as we typically think of pre-Stonewall life; and b) the facts were often hiding in plain sight, although some people performed a dance of denial.

JP: It seems that Lynes was often navigating this reality in his life and in his art. As you note, his male nudes were too explicit to be publicly shown or sold for publication. How much of this work was known or circulated at the time he was creating it? And what do you think motivated him to create these male nudes throughout his life even though they had a limited public presence?

AE: His male nude photography was certainly known among close friends and some family. In the former instance, I would stress his friendships with the so-called Magic Realists like Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and later George Tooker—all of whom did figurative work. Cadmus and French’s imagery included homoerotic scenarios both implicit and explicit, and their shared values in this element in their work would have encouraged George to share his male nudes with them. When new friends such as the pornographic writer and tattoo artist Sam Steward entered Lynes’ life, it was natural for Lynes to allow Steward to view his male nudes and select a number of them as a gift that would not be subject to claims of criminally selling “obscene” materials.

Lynes felt compelled to work with the male nude. He marveled at beauty and male desirability and worked out his attractions by documenting the dancers and models and young men who were recommended to him. It was a kind of obsession and not a commercial endeavor. Indeed, it was rather late in his career when he finally allowed a European publication, the Swiss homophile magazine Der Kreis [The Circle], to reproduce select works. Der Kreis’ editor promoted Lynes’ male nudes as among the finest that the magazine had ever published. It was a safe venue for Lynes, since it was a European magazine, though available by subscription in the U.S., and it undoubtedly expanded Lynes’ reputation to a European gay audience.

JP: Lynes met Alfred Kinsey in the early 1950s, and Kinsey purchased many of his male nude photographs for his growing archive at the Kinsey Institute in Indiana. How important was this relationship for Lynes?

AE: Kinsey gave Lynes’ photography with the male nude the imprimatur of his expertise as a scientist. Lynes clearly needed this—certification by an expert in the field of human sexuality who took his photographs seriously as important documents of same-sex relations. Lynes did not want to be thought of as a pornographer, which may have been an issue of class. Kinsey was nonjudgmental and, in return, was given a privileged entrée into a world of sexually marginalized men and women, many of them artists. Erotic representation was an important aspect of Kinsey’s inquiry, so Lynes surely felt that he was contributing to a larger cause. He, like his two intimate companions (Wescott and Wheeler), and like others they recommended to Kinsey, was interviewed by him or his team. This, too, gave them all the sense of contributing to a more enlightened future for their “tribe.” It may not have been political activism as we know it today, but it was certainly an important form of community building, which I believe is foundational to political engagement.

JP: Can you say more about this “issue of class”? I’ve always been struck by how this was a simmering tension for Lynes throughout his career. While he moved in the cosmopolitan world dominated by many wealthy patrons, there’s a sense in the book that he struggled to be part of “our” world. Also, he didn’t have the status of an artist but rather of a photographer, which didn’t hold the same importance within these circles as a writer or painter.

AE: It was important to Lynes, especially in communications with Kinsey, that his male nudes not be characterized as pornographic. Kinsey himself suggested that Lynes photograph male couples “in action.” In response Lynes produced some images of couples in more obvious sexual embrace, but he essentially shied from work of that kind. When he brought two or more men together, he preferred to maintain a certain æsthetic formality.

As for the issue of class, the great friend of Lynes’ last decade, the artist Bernard Perlin, characterized the Lynes circle as the “cufflink crowd.” Lynes almost always lived beyond his means, for he put great store in making a showcase of his living situation—with fine objets and good furnishings and art on the walls everywhere. Despite this desire to dress well, live well, and be a member of the smart set, he also sought out youthful models who may have had few financial resources, and others who might be considered working-class. There were occasional young African-American men and Latinos, and sometimes he didn’t hesitate to cross the standard ethnic boundaries of his society. I think he sought to have a good rapport with his male models, and if they were congenial but of another class, so be it. He played a mentoring role as he matured, just as Wheeler and Wescott had mentored him. This archetypal mentoring relationship from antiquity remained in force among the “cufflink crowd.”

JP: What struck me throughout your book was the fluidity of the sexual lives of Lynes and those in his circle. Men who were primarily heterosexual were often keen on having sex with Lynes or another man. Conversely, men who mostly had sex with other men might indulge in affairs with women. Do you think these unbounded sexual lives shaped Lynes’ creative work?

AE: I wouldn’t want to overstate the “unboundedness” of the sex lives of Lynes and his intersecting networks. To be sure, there were some straight men who occasionally flipped to the other side, and Lynes himself had one significant sexual relationship with a woman who had long been a favorite fashion model and dear friend. Then, too, men like Jared French and Lincoln Kirstein both married women while leading active gay lives. French and Paul Cadmus seem to have continued their relationship even after French married Margaret. And Lynes’ lover, Monroe Wheeler, had some heterosexual relationships in his early adulthood. At one point, Lynes even feared that “Monie” was going to marry his business partner, Barbara Harrison, who was a wonderful addition to their cosmopolitan and cultural camaraderie.

Nevertheless, to respond to your larger point about how these examples of sexual boundary-crossing might have influenced Lynes’ creative life, I would stress something that might seem terribly démodé, if not downright conservative or backward. We need to remember that the identity labeling we live with today was not as common back then, nor “enforced” as it is now (though today’s concepts of sexual fluidity and gender as nonbinary could change all that). In Lynes’ time, the possibility of testing different sexual waters was possibly quite common. No one thought it meant you were making a lifelong commitment or betraying your essential nature.

JP: While Lynes work has gained more recognition over the past few decades and more people know about his photography and his life, is there one misconception that we still harbor about his life or work?

AE: One misconception that I’d like to correct is the oft-repeated claim that many of his male nude photographs were “destroyed” by his beloved younger brother Russell Lynes. Russell was not some fearful homophobe who was ashamed of his gay brother. It is true that George Lynes himself destroyed many negatives, in one instance because he was leaving New York for Hollywood—a two-year fiasco of a move—and simply wanted to lighten his load. And when he was returning to New York from the Berkshires during the last summer of his life, he and Monroe took a train into the city and apparently destroyed many of his fashion photographs. But Lynes did so because he regarded these images as inferior to his best work—which he certainly considered to be his work with the male nude.

JP: What do you think is the greatest legacy of Lynes’ as an artist?

AE: His courage. He worked at a time when producing homoerotic images of the kind he did was practically unthinkable. Such pictures were subject to postal confiscation and fines. You could not publish such pictures unless you did so in an underground context. Lynes’ images of male beauty and erotic community anticipated a freer sexual circumstance for gay men—that is, a social order that would allow the freedoms we enjoy today.

About the Authors

James Polchin is the author of Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall.

Allen Ellenzweig is a cultural critic and commentator who has published in numerous arts and general interest periodicals. His landmark history, The Homoerotic Photograph: Male Images from Durieu/Delacroix to Mapplethorpe, was published in 1992. He is a regular contributor to the Gay & Lesbian Review and has taught in the Writing Program of Rutgers University.

This article is reprinted with permission of the Gay and Lesbian Review.