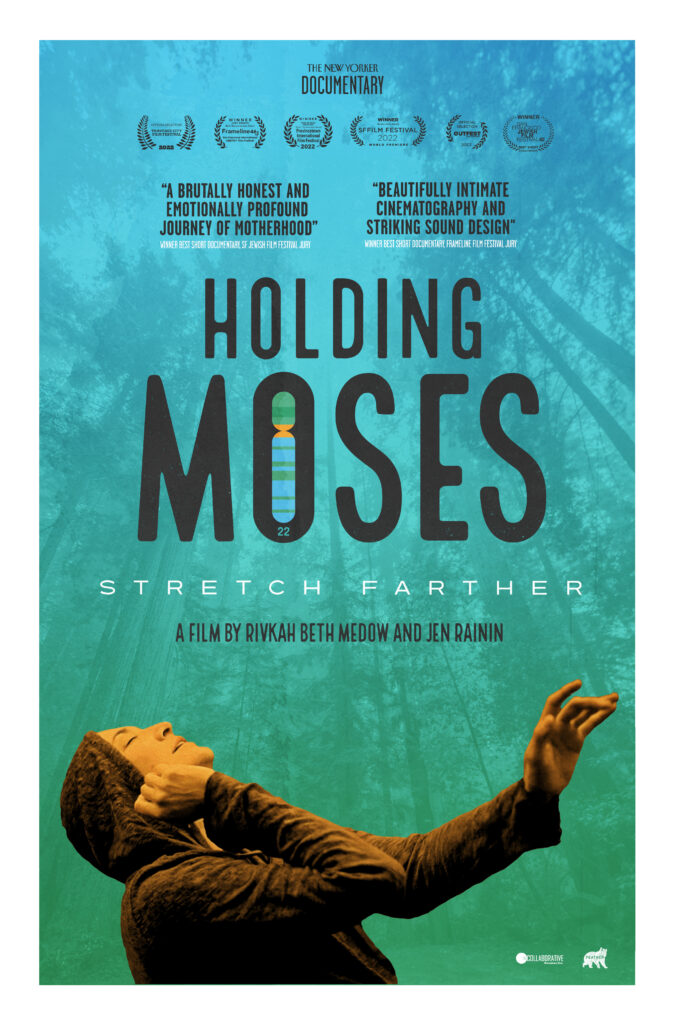

Landmark queer film Holding Moses has been voted Oscar-worthy!

Great news for the filmmakers and audiences of Holding Moses: the true, intimate, and revelatory story of butch queer mom Randi Rader, who must come to terms with her son’s severe disability, is now eligible for an Academy Award in its category of documentary short.

Jen Rainin, who co-directed the film with Rivkah Beth Medow, told Queer Forty: “Holding Moses being shortlisted for an Academy Award is a huge win for LGBTQ+ visibility and an incredible thrill for us!”

Rainin founded Frankly Speaking Films with Medow in 2020 to produce cinematic offerings that center strong LGBTQ+ women and non-binary people to increase visibility and spark change. Rainin, who focuses her filmmaking on building community, deepening understanding of social justice issues, and telling great stories, continued: “Now is the time to show a nuanced story of queer family, love, and community that enables conversations which move us individually and as a group toward greater inclusivity and positive action in our worlds. We are so grateful to Randi for sharing her story. Rivkah and I are both caregivers and mothers — and to see those stories, our stories, validated through Randi’s is deeply moving.”

See the full shortlist in 10 categories for the 2023 Oscars here.

Previously, Rainin and Medow presented the world with the excellent feature documentary, Ahead of the Curve, about the history of the world’s most significant publication for queer women — Curve magazine.

Holding Moses is now streaming for free via The New Yorker. Watch the film here.

One of the best queer films I’ve seen this year, which I saw, coincidentally, during National Family Caregivers Month, Holding Moses made me question a lot of the assumptions we have around queer parents-to-be, and birthing and raising children as reflections of ourselves and societal expectations.

The story focuses on mom of three Randi, who studied Butoh dance in Japan before performing in the Broadway show STOMP. Always wanting to be a mom, Randi gets inseminated and gives birth Moses who is profoundly disabled—physically, intellectually, and emotionally. Randi must overcome her own severe grief and find a way to understand, learn, and love her son as he is.

This is a journey we never get to see and it makes visible the expectations felt by queer parents to achieve perfection in parenthood—in the child and in themselves as parents. As a dancer, for whom movement and the body is vital, Randi must struggle to interpret and love her son’s “imperfect” being. But in their divergent physicality there is a key, and it is richly ironic the extent to which different Randi must unpack and accept this other type of queerness.

Such profound insight is offered by filmmaker Rivkah Beth Medow in part because—as well as being a gifted artist—she has complete access to the subject: Randi is her girlfriend, and Medow is also a mother, on her own journey of grief around being a caregiver. “Randi and I recorded the story of how she reckoned with her feelings of grief around birthing Moses…We set up a mic just the two of us and Randi shared for three hours with a fierce honesty that became the audio track for Holding Moses. So the intimacy you’re hearing in Randi’s voice is that of a mother revealing her rawest self to me, the person she trusts most in the world.”

Caregivers as a group are largely invisible, and queer people are often caregivers; additionally, LGBTQ folks can overlook their ableism because they already feel marginalized or stigmatized by their queerness and can lean towards exceptionalism. Holding Moses examines the nexus of these issues. Therefore, the shame Randi feels and most overcome while caring for her disabled child is a form of representation that inspired in the viewer both gratitude and admiration.

Medow told Queer Forty, “You know, we didn’t think of it as an interview at the time. I set up a microphone and we knew we were recording it, but she could be so vulnerable because she was telling the story to me.” That audio of the voiceover is used to powerful and counterpointing effect with Randi’s solo movement sequences, as if she knows her body and the art of movement and touch will hold the key to acceptance.

In working with her girlfriend, who was also her subject, Medow was aware of the trust placed in her. “I’m so happy to be making media in a time where consent is such an honored concept in media making, whether it’s about a partner or a loved one or a participant in a film. I think that the idea of consent and the idea of helping as much as we can as a filmmaker—I see my responsibility as helping to make those spaces safe, and creating something that is of service to the world. I’m not interested in just making content.”

Medow says when they decided to expand that conversation into a film, it felt like a “gift… a larger good that a story can do in the world.” As a filmmaker, Medow then had to think whose story this was, and how it should be received.

“We settled on a logline that we thought would give people the information that this was Randi’s story. It’s not Moses’s story. It’s a caregiver story. And we wanted to build dance into it and make sure that there was some poetry in the logline so that people could get an understanding of what they can expect with the film. So our logline ends up being: A Broadway performer becomes a mother braiding rhythm, grief and time with joy on her path to connect with her profoundly disabled son.

Medow says making the film was a joy in its process, especially the many “rich conversations” it produced with Randi as the themes of the film emerged. “Caregivers of atypical children are considered either saints or there’s a huge shame narrative around it,” says Medow. And then there was Randi’s unique story and the questions it raises about making queer family. “So few people have her exact experience,” says Medow, and yet something happens that is miraculous about this film: its specificity makes it universal, and there is space for the viewer to bring their own experience to what they are seeing. “Many of us, if not all of us, are caregivers at some point in our lives,” notes Medow. “Whether it’s to children, whether it’s to parents, whether it’s to friends—especially in queer community.”

And perhaps one of the last taboos in the queer community, aside from agism, is ableism. We have not fully examined or embraced disabled folks, and thinking of Randi’s aspiration to attain peak aptitude as a dancer—and the exceptionalism pursued by most performance artists—Moses’ disability is hard for her to immediately integrate into her view of queer parenting.

In conversation with Medow, something profound came into view for me. In the history of queer activism we have pleaded with the mainstream to change and to understand us. In Holding Moses we see Randi’s journey is about letting go of her own normalized view of child-rearing.

“Randi has a really important journey around her own understanding that she was the one who needed to change and not Moses. It took a few years to really understand that,” says Medow. The reason for this seems to me twofold: Our mainstream culture doesn’t know how to deal with children with impairments; and our queer community has often had to transcend our own othering as devalued or diseased bodies.

“We have a world that has for centuries devalued bodies that are different,” says Medow. “Heteronormative pressures reduce our expansive humanity. We want to be full spectrum humans, right? We want to be able to be who we are. And we don’t want to feel shame. We want to be able to present ourselves as we see ourselves. I’m so grateful to The New Yorker for seeing the value of this film and seeing the way in which it can be part of a conversation. It can join a conversation,” says Medow.

It should be noted that Holding Moses is the only queer-themed film in the Documentary Shorts category for the upcoming Academy Awards. This healing, transformative film is being acknowledged as the gift it was intended to be.

Watch Holding Moses here.