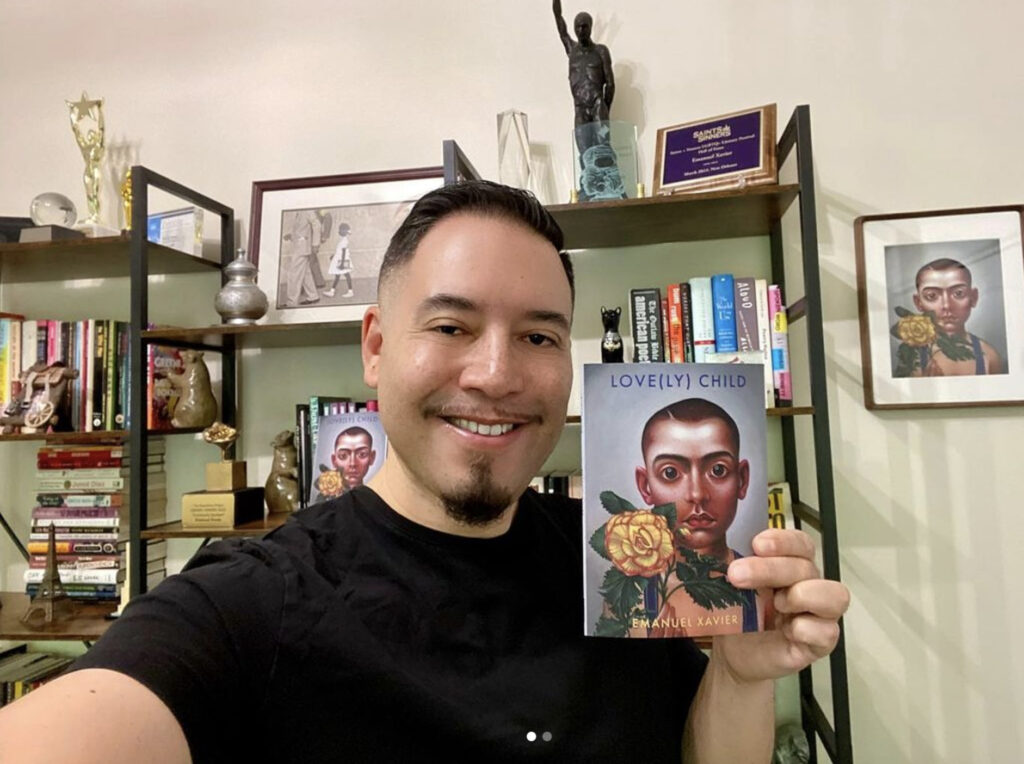

Latinx poet Emanuel Xavier’s latest book is out now!

Love(ly) Child is a thought-provoking collection of poetry that delves into themes of identity, love, and self-discovery.

Influenced by the homophobic hip hop of the time, in the early ‘90s, there were few openly gay poets in the spoken word scene. Enter a former homeless hustler from the Paris is Burning ball/House community, Emanuel Xavier helped open the doors for queer poets of color to take centerstage and speak their truths. Without so much as passion and perseverance, he became an LGBTQ+ Icon, as proclaimed by The Equality Forum. Long before diversity, equity, and inclusion were buzz words, he gave voice to his unique experiences and tackled politics, sexuality, and religion with poetry.

“In the ‘90s, this former homeless teen, hustler, House/ballroom/pier queen dared to step into the homophobic spoken word poetry scene of the time and share his world without so much as passion and perseverance,” Emanuel posted on Instagram recently. “Throughout the eras, before DEI, I’ve had many highs and lows but after five full length poetry collections, a novel, editing three anthologies, and a selected poems collection, I am #stillhere and looking forward to continue giving voice to my experiences as an LGBTQ+ and Latinx writer.”

In praise of Love(ly) Child Michael Bronski writes “Violence was an artform.” Thus writes poet Emanuel Xavier about growing up while fiercely witnessing and surviving the terrorism that lurks in the family, the streets, and sexual encounters. In Love(ly) Child – his most powerful work yet – anger cuts through memory and propriety as he methodically dismantles cultural platitudes: love, care, safety, and innocence. Specters of family brokenness, colonialism, desolate cityscapes, outlaw love, and AIDS haunt these poems. Here, DEI stands for “disenfranchise, exclude, and ignore,” and death hovers over these poems like the stillness of a quiet city night that is always vanquished by the hope of dawn. In Love(ly) Child, Xavier reminds us that as dire as our pasts may be, “Compassion is our only inheritance/ bold to love what we cannot hold.” Queer Forty got a chance to catch up with Emanuel to find out more.

Queer Forty: Tell us about tackling politics, sexuality, and religion through poetry.

Emanuel Xavier: I found it necessary to tackle all these things from the very beginning of my career. Once I discovered I wanted to dare be a poet, I was very inspired by the Beatnik generation. Spoken word poetry was becoming very popular in the early 90s and there was a resurgence of political poetry. There were several other queer poets of color before me that were prominent on the literary scene, but the spoken word poetry scene was still seen as a derivative of hip hop and rap, which was very homophobic. Once we infiltrated the spoken word poetry scene, we enjoyed a certain level of success. However, somewhere along the way, for a period, it became rather unfashionable to include politics, sexuality, and religion in poetry. Fortunately, we’re at a place again where there seems to be room for both, as it should be.

Can you talk about the significance of language and word choice in your work?

I have used a lot of Spanglish in my poetry throughout my career because it is the way I speak. I always encouraged those who didn’t understand a certain word or phrase to look it up. Even if you don’t know what a word or phrase means, you should be able to determine the concept or thought behind it in the context of a poem. I’ve chosen to italicize words in Spanish in my printed poems. There is some debate about what the proper way may be to present this in literature, but I think it’s simply a matter of preference. I’m not here to tell anyone how to write or express themselves.

Is there a moment, image, or memory from your childhood or youth that somehow hints that you’d write poems as an adult

My only real father figure as a child, even if from a distance, was my maternal grandfather. He was a journalist in Ecuador, and I had such admiration for him as a little boy. He would send me children’s books, the ones with records on the back sleeve, that I loved to get, read, and listen to. Everything from The Ugly Duckling to The Wizard of Oz. I LOVED getting these shipped to me from South America and had a little record player. Amidst all the pain, it is a very happy memory of my childhood and I wanted to be a writer like him someday.

Your work has been celebrated for its representation of queer Latinx experiences. How important is it to you to center these identities in your writing, and how has that impacted your creative process?

I was often told not to box myself into being a queer poet of color, but it was important for me because I had to self-discover poets like Assotto Saint and Audre Lorde. I wasn’t taught much outside of Shakespeare in school. I loved going to the library and picking up books which would now be banned to find others with similar experiences to my own—feeling different, coming to terms with my sexuality and the color of my skin. It was necessary and lifesaving and I wanted to share my truth and the world around me so that someone out there knew they weren’t alone in this world. It is wonderful when a writer can capture an outside experience or share happiness or self-help poetry. However, my work has always been personal, confessional, dark. It remains important for me to center these identities in my writing because poetry saved me and has helped me heal. Maybe it inspires others.

Let’s talk a little more about homophobic hip-hop in the 90’s and the affect it had on your writing?

In ballroom, I walked the Banjee Realness categories and I played with being both hypermasculine and feminine. After years of being bullied as a kid for being soft spoken and girly, it was about survival when walking through the projects and not getting gay-bashed, which I was eventually anyways. So, when I came onto the spoken word poetry scene many of my earlier poems were simply about culture and they seemingly crossed over to the mainstream because I didn’t appear to be gay. Then I would read something about being getting kicked out as a teen for being gay and the mood would change. It was sort of a reveal, but it was honest, and I demanded attention and respect up on the stage. I would often find myself as the token gay poet in many hip hop nights. The best was getting invited to erotic poetry events where I was reading poems about getting fucked in front of straight audiences. Interesting enough, even when I appeared on Russell Simmons presents Def Poetry on HBO in 2003 and 2005, the poems they asked me to tape were my earlier cultural poems which only hinted at my sexuality. I remember taping more provocative stuff that never aired.

Queer Poets of Color: Who are you reading?

I am really excited about the new Cheryl Boyce-Taylor collection. She is one of the reasons I became a spoken word poet and, perhaps more effectively than myself, has remained a presence on the scene all these years. Have you read Siaara Freeman? Urbanshee was amazing and inspiring. I’m excited to get to Charif Shanahan’s latest collection. And I was thrilled to provide a blurb for Octavio R. Gonzalez’s Limerence.

Reginald Harris said you are a “poetic truth teller.” Is it painful at times to revisit these truths?

The short answer is a definitive yes. Writing is a solitary act and sometimes I often find myself crying as I write certain truths. Other times I’m afraid of how I will be judged or criticized.

If you were to choose three songs as Love(ly) Child soundtrack what would they be?

“Love Child” by Diana Ross and The Supremes. I must also note the early ‘90s freestyle version by a girl group named Sweet Sensation which introduced me to the classic.

A popular Spanish song from the ‘80s by a female-led new wave group called Alaska y Dinarama called “A Quien Le Importa” which was remade and popularized as a gay anthem by Thalia, though the original version is the TRUE classic.

And, lastly, “Family Affair” by Sly and the Family Stone because many of the poems are about personal discoveries about my own paternal family and history.

You have also been doing a ton of community work to further the visibility for LGBTQ writers. Can you share some exciting news from this community work?

It’s been quite the journey because I remember trying to introduce spoken word poetry to the LGBTQ+ community with a monthly series called Realness & Rhythms at A Different Light Bookstore in NYC and the House of Xavier’s Glam Slam competitions. That seems like a lifetime ago now that I joined the Board of The Publishing Triangle. We’ve been doing a lot to celebrate LGBTQ+ writers with new awards and a monthly reading series, OUTspoken, at the Bureau of General Service—Queer Division in New York City. I also founded The Penguin Random House LGBTQ+ Network years ago as an employee of the company before DEI was an initiative in the corporate world. It was the first LGBTQ+ group for a major publishing house and I got them to sponsor LGBTQ+ publishing events like the Lambda Literary Awards. I’ve also worked with other organizations to fund LGBTQ+ writers but that work remains on the down low.

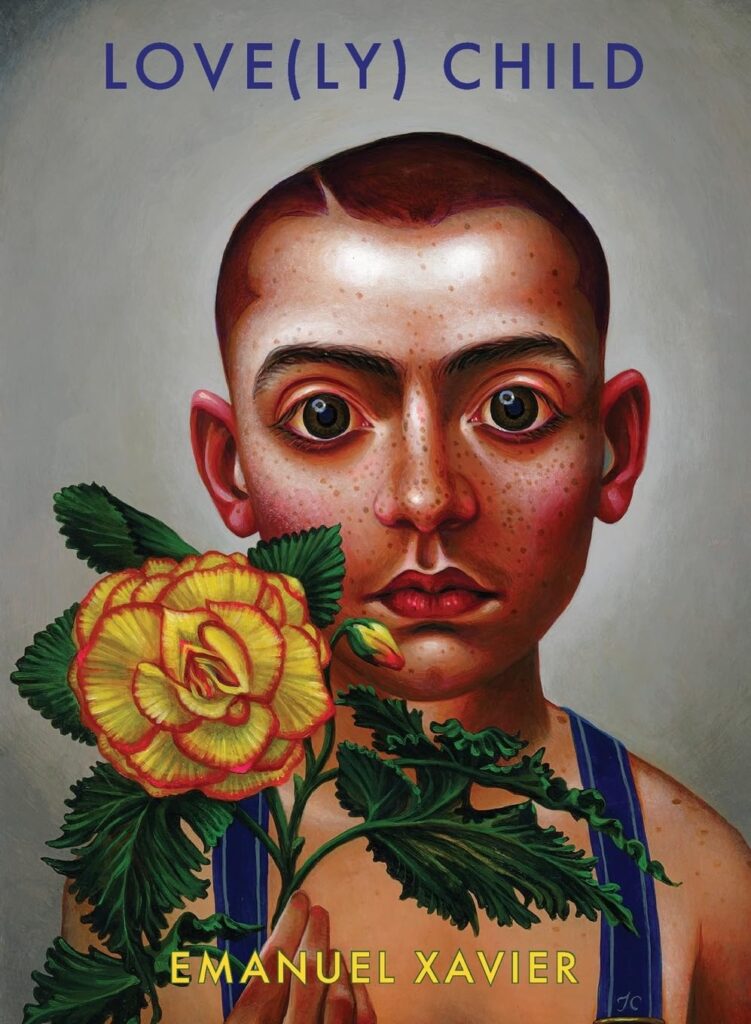

Last but not least, Love(ly) Child has one of the best book covers we have seen. Tell us about the development of this cover?

I LOVE Timothy Cummings’ artwork and have been a fan from the moment I discovered him through the annual Saints & Sinners Festival. I’ve always been a huge fan of pop art and his work spoke to me in much the same way. I was either cruised or pitied by Basquiat at the West Side Highway piers while I was hustling as an underage teen in the mid ‘80s. He stared at me for hours, probably on a bender. I didn’t know who he was until seeing him on the cover of a newspaper on Christopher Street announcing his death a few weeks later. I became obsessed, especially after finding out he had dated Madonna. I also hung out a lot with Juan Xtravaganza who had many personal stories to share about Keith Haring, as he had been one of his lovers. I didn’t mind being dubbed a “street poet” when I first came on to the scene because they were known as street artists, and I felt a connection to them. Timothy’s work reminded me a lot of them, and I got to meet him this past year when I was down there to be inducted into the Saints & Sinners Hall of Fame and we hit it off as artists. His visuals and my poetry seemed to be in a similar artistic vein, and we were thrilled to collaborate. I’ve never had an opportunity to do something like this before, so it was a true honor to get to work with him. I sent him an advanced copy of the manuscript and what he came up with was gorgeous. I’m glad I got to inspire him, and I hope it brings much deserved attention to his incredible work as an artist.

Love(ly) Child is available from Rebel Satori Press and Bookshop.org.