Leslie Cohen: Chapters of a lesbian life

Leslie Cohen, activist, women’s nightlife promoter, and most recently author of the memoir, The Audacity of a Kiss, has passed away. We republish this story in her honor. May her memory be a blessing and part of lesbian history forever.

As the baby boomer generations of LGBTQ people in their 70s age, we are in danger of losing their stories.

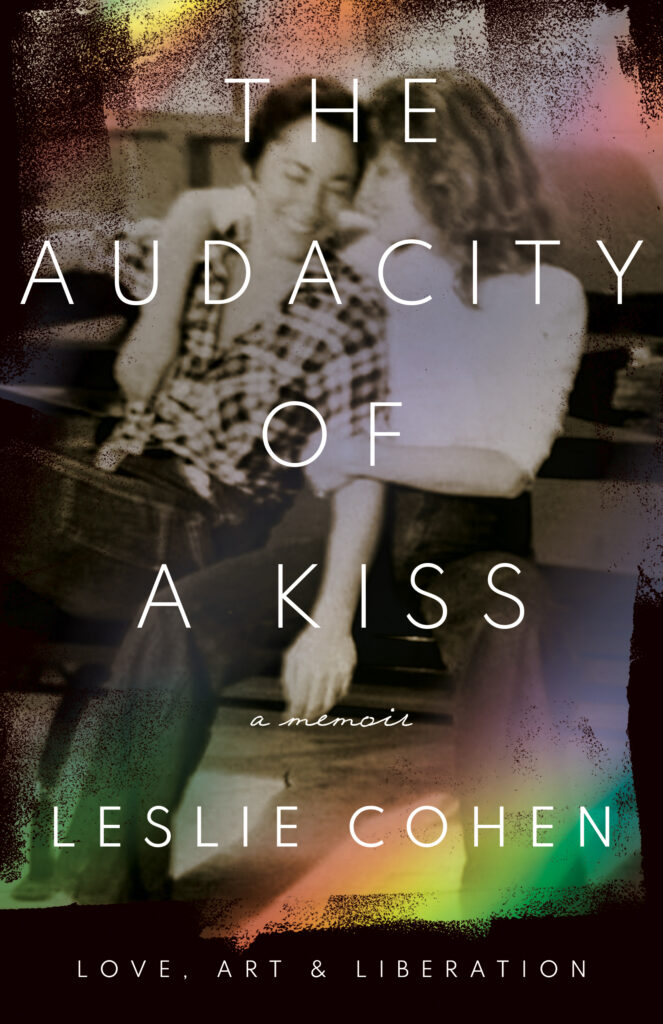

Leslie Cohen, 75, wanted to tell her own story, and with it an overview of the era in which she came of age as a lesbian. That time includes the stories of so many lesbian and bisexual women of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s and that era pre- and immediately post-Stonewall is at the heart of Cohen’s new memoir, Audacity of a Kiss: Love, Art and Liberation.

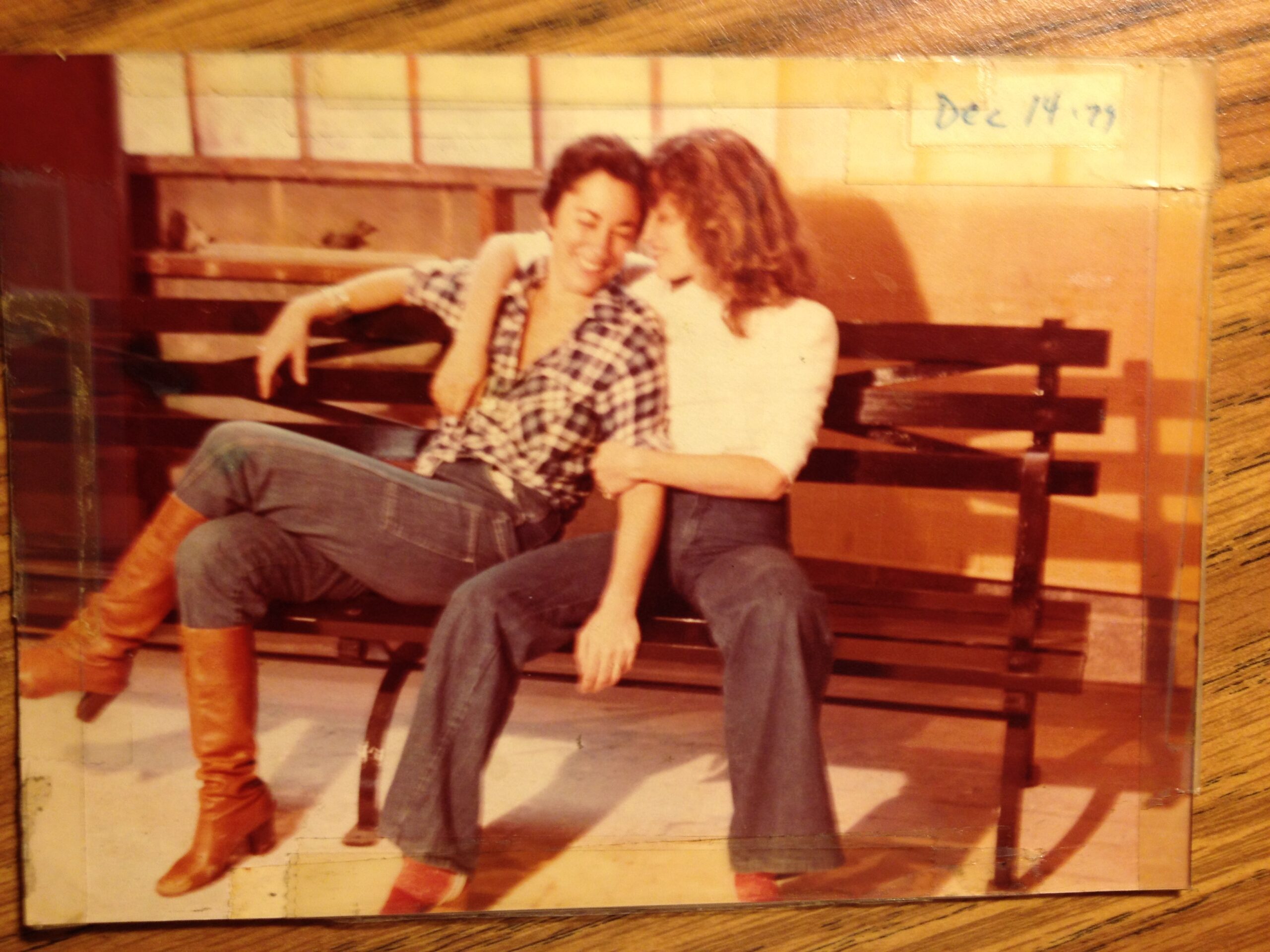

The book was a labor of love 12 years in the writing. Leslie Cohen’s isn’t one of the household names of gay liberation. Yet there she sits on a bench in Christopher Street Park, memorialized with her now-wife, Beth Suskin, outside the Stonewall Inn bar in Greenwich Village.

This is where the modern LGBTQ civil rights movement began, with the first punch thrown at police by lesbian drag entertainer Stormé DeLarverie in the days of rage now known as the Stonewall Rebellion, at the end of June 1969.

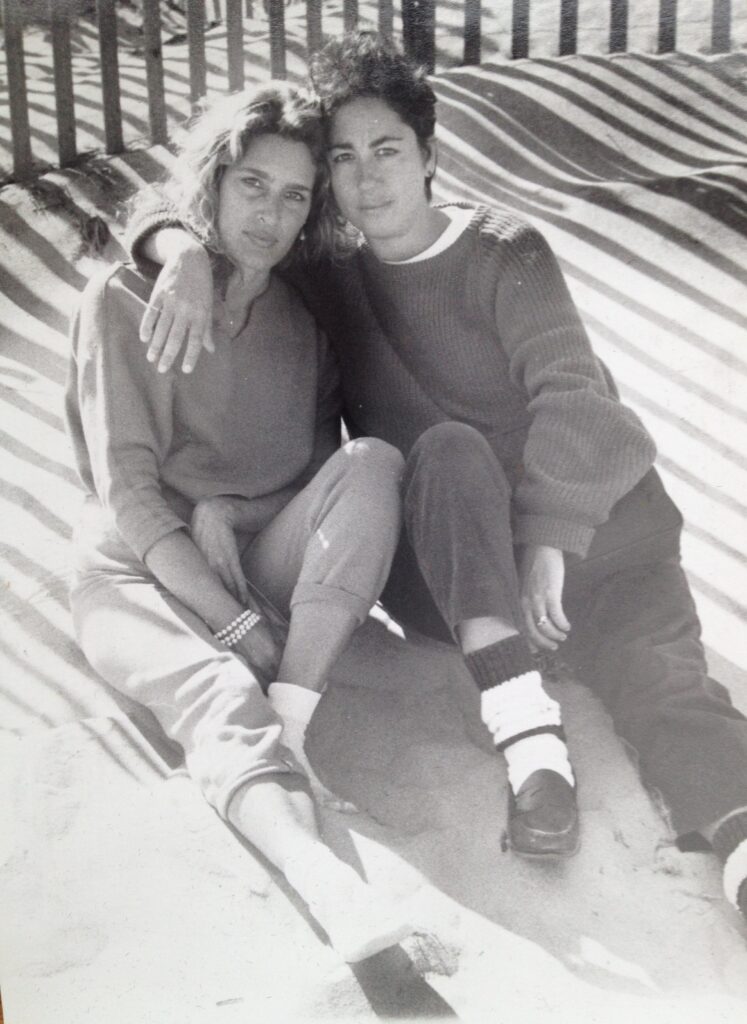

Cohen and Suskin are the lesbian couple in the four-figure sculpture that also includes two gay men standing nearby, rendered by renowned American artist and sculptor George Segal. The dynamic, life-sized work, made in 1980, is titled Gay Liberation. It was commissioned in memory of the 1969 Stonewall riots and is the first piece of public art dedicated to LGBT rights.

There are two castings of this historic piece, one now housed at the Gay Liberation Monument in Greenwich Village and the other at Stanford University’s Main Quad in California’s Silicon Valley. In March 2000, the Stonewall Inn was designated a National Historic Landmark.

That statue is part of Leslie Cohen’s legacy as a lesbian New Yorker in the early days of the modern LGBTQ civil rights movement. Cohen said in an interview from her vacation cabin in the woods, that she wanted people “to know our history. I wanted them to know that these women spent their lives together [Suskin and Cohen we met in 1965 and have been a couple for nearly 45 years of that time] and were very much in love.”

Cohen says, “I wanted to inform and inspire and help those who are suffering with their identity to see a positive future for themselves.” A future that was not presented to her as an option when she was coming of age as a young lesbian in the closeted 1950s.

Another aspect of Cohen’s legacy is her co-founding of the Sahara club — what has been called the best lesbian bar ever. Sahara was the first lesbian bar to be women-owned and operated in an era when, as Stonewall epitomized, the police and the Mafia worked hand-in-glove to maintain control over patrons of gay and lesbian bars and clubs. As historians like Lillian Faderman, Jonathan Katz and Martin Duberman have detailed, these bars were routinely raided and patrons were often arrested and then blackmailed later.

Cohen is warm and engaging, with a ready laugh. She’s a natural raconteur who tells many stories of the early years of her own lesbian life and that era. Much of that storytelling forms the basis for Cohen’s memoir which is part personal history, part lesbian history and many parts love story. Cohen told Q40 how hard it was to find one’s place as an out lesbian in that very closeted time. It was, she said, “My motivation for writing this book”—to put that history down before it was lost. She is excited about Audacity of a Kiss. “This is the first book I’ve ever written. It’s kind of overwhelming.” She jokes, “I’m a person who loves to talk about herself,” but says the process of doing that in a memoir was painstaking, emotional, and took a dozen years.

Cohen explains that who she became was very much about where she began. “I was born in 1947 and grew up in the 1950s—the ‘Mad Men’ era. Men worked, women stayed home.” The roles laid out for women were limited, Cohen says. “It was taboo to be gay.”

When she went away to Buffalo to a teacher’s college in 1965, Cohen found herself on the cusp of social change. By 1967 college students everywhere were taking political stands. “The times were changing. College students were rebelling.” Cohen says that women went to teaching colleges because other avenues were not encouraged. She says her own parents didn’t encourage her to step outside the limited roles for women in the 1950s and ’60s. And her father’s view was, “She’s a pretty girl, she’ll hook up with someone.”

But Cohen was aching for a change and to be her authentic self—a term not used at that time. She says that gender stereotypes defined her era. She was a “tomboy” who played sports and wasn’t into “girly” things. “So many things were only for boys,” she laments.

But even when she went off to college, she could already feel gender oppression threatening to subsume her and her desires. Art saved her. “I always had a visceral connection to art,” Cohen explains, but “it wasn’t realistic to go into art.” Nevertheless, Cohen went to Italy to study for a year. “I wanted to experiment. I wanted adventure.” She came back to the States and “I switched to art history. It appealed so deeply to me. It was part of my nature to explore things.”

A lot was roiling within Cohen at this time. She says “my gender dysphoria” was a driving force, as well as her desire to have an independent life outside the boundaries she’d witnessed growing up. She got her master’s degree and landed at the prestigious Artforum magazine, founded a few years earlier in 1962.

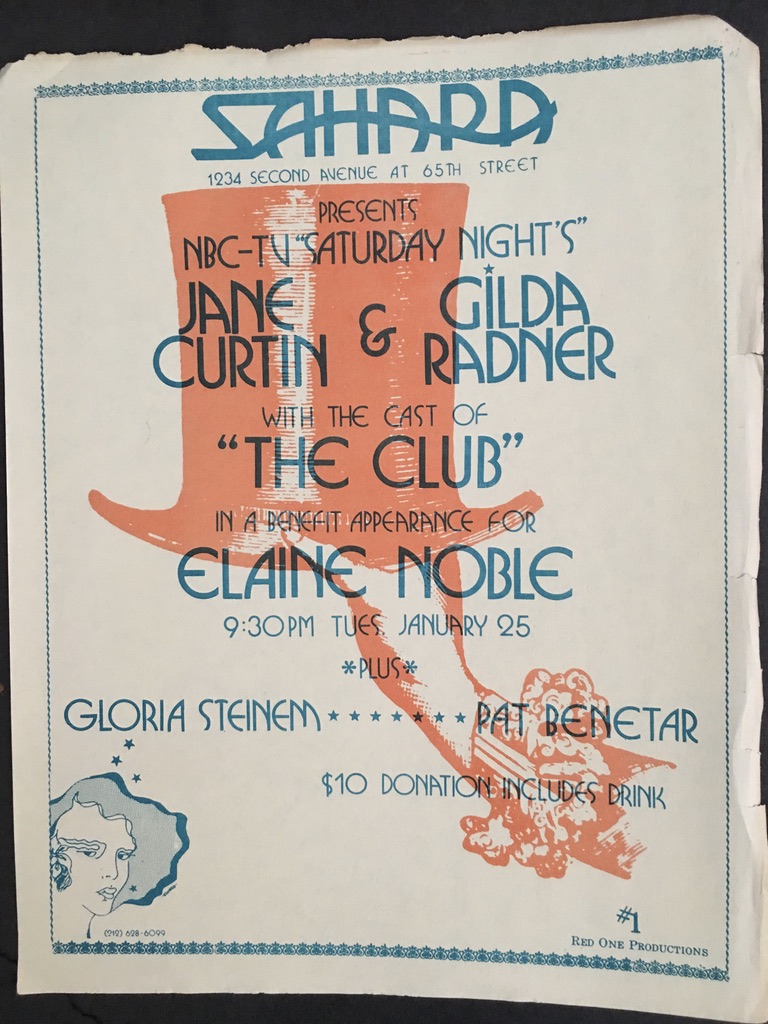

Cohen says she was thrust into a “world of money and privilege and wealth. It was expansive.” And it led to her co-founding Sahara. “I had this idea of opening a nightclub. If you venture out in one thing, you feel you can do other things,” she said. Sahara was one of those other things. “Sahara was the first club created and owned by women for women in 1976 in New York City,” Cohen said.

In her memoir, Cohen writes, “Our club would be an oasis in the desert of conformity. It would be a place in the world where women could feel self-respected and safe.”

The book explores just how true that was. Photos of flyers from events held at Sahara are full of luminaries of the time, including feminist icon Gloria Steinem and entertainers like Nona Hendryx, comedians Gilda Radner and Jane Curtin and singer Pat Benatar. Jane Fonda and then- husband and anti-war activist Tom Hayden hosted a fundraiser for early lesbian politician Elaine Noble. Noble was the first openly lesbian or gay candidate elected to a state legislature.

Cohen says that she knew “if I did not memorialize Sahara in some fashion, it would be lost to the annals of history. My partners, Michelle Florea, Barbara Russo and Linda Goldfarb and I had created a groundbreaking women’s club.”

She says that their “accomplishments and the club’s significance were being disregarded, never mentioned in the 30 plus years since in any writings on the history of feminism, gay rights or nightclubs, straight, gay or otherwise, of that freewheeling era.”

Cohen fears lesbian erasure and her era being lost to history if no record is kept of these stories. She felt that the women of Sahara were being made “invisible” and “added to the pile of absentee women’s history.”

Given the work she, her partners in the venture and the women who came to Sahara and loved it all participated in, Cohen says her motivation in her memoir was “to record for history’s sake what I and others thought was an important contribution to women and LGBTQ history. I realized that if I didn’t write the story, no one else would.” Cohen is adamant about “the importance of lesbian bars in terms of community. Lesbians need that space for just them. The need for it is really strong.” And she adds that lesbian desire also gets erased when the impact of lesbian bars is not acknowledged. “You want to go out and cruise, you want to be around women.”

“I relish being submerged in women’s energy and vibes. At a lesbian bar or club, women don’t have to worry about is it safe or not safe? I hope people understand that we still need lesbian bars.”

But Cohen acknowledges it has always been a “tough road for lesbian bars to stay in business” because lesbians don’t have the money their gay male peers have always had access to. Cohen has been involved with the Lesbian Bar Project, which was founded in 2020. The Lesbian Bar Project is a campaign created by Erica Rose and Elina Street to “celebrate, support, and preserve the remaining lesbian bars in the U.S.”

Throughout these many stories of Cohen’s life is the thread that runs through it all: Her love affair with and marriage to Beth Suskin. The two met in 1965, but did not become a couple until some years later. They’ve been together nearly 45 years and when Cohen talks about Suskin, it is with deep affection and respect.

Like many lesbians, Cohen was in and out of relationships throughout her 20s. But she says, “by the time I was 28, 29 I knew what I needed and wanted.” And there was Beth. “It was written in the stars,” Cohen says. “I was very fortunate. I was always a romantic.”

She says the couple has “the most moral code. She tells the truth. She loves me. She doesn’t want to hurt me. I adore her. We’re best friends.”

Cohen stresses the importance of partnering with someone with whom you have a deep friendship, not just chemistry. And who is honest and loyal.

“The passion years,” she says, shift over time. “The commitment and honesty,” she says, are essential. “In the end, love is all that really matters.”

As for her advice about how to live an authentic life in times that often demand dissembling and pretense, Cohen says, “Many of us don’t have a clear path starting off. Regardless, have faith and live your best life. As you age, the twists and turns coalesce and it all makes sense.”