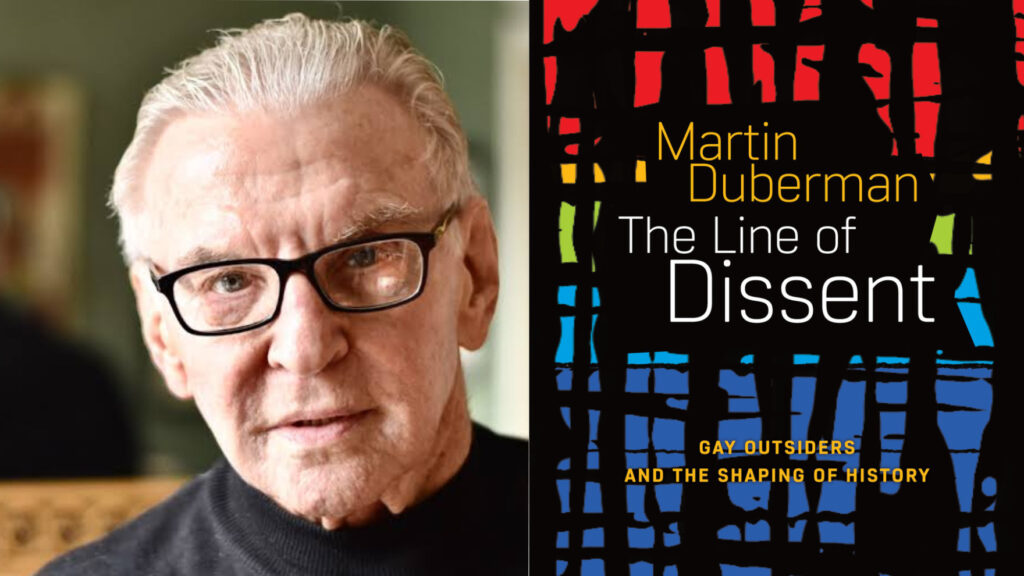

Martin Duberman’s breathtaking account of LGBTQ history

A new book of essays offers a wild ride covering a breathtaking swath of LGBTQ+ history, all brought to you in Martin Duberman’s informative, easygoing style of writing.

These essays (with a few exceptions) first appeared in The G&LR, a national, bimonthly magazine. The first to be published in 1997 was an in-depth profile of Edward Sagarin, author of The Homosexual in America (1951), dubbed “the Father of the Homophile Movement.” The latest, from 2022, provides new insights into the work of Alfred Kinsey, who pretty much invented the field of sex research, and his acolyte C.A. Tripp, author of the explosive 1975 book The Homosexual Matrix.

The Line of Dissent suggests a common denominator for a truly diverse group of individuals: trailblazers who forged new ways of thinking or being, and who all made major contributions to LGBT life and culture. Activists, poets, artists, and daredevils. A three-part series on impresario Lincoln Kirstein reveals how he brought the art of ballet to America. Several profiles can be found at the intersection of the LGBT struggle and leftist politics: activist Barbara Deming and her strategy of “direct action nonviolence”; Sylvia Rivera, who sparked the transgender revolution decades before her time; and bisexual Andrea Dworkin, the radical second wave feminist. Another group includes visual artists such as painter Robert Rauschenberg and designer Ed Wormley, and poets such as W. H. Auden and Black activist Essex Hemphill. There’s even a chapter on lesbian speedboat racer Joe Carstairs, who burst all kinds of barriers when she won major trophies in the 1920s.

From The Preface by Martin Duberman

It’s one of history’s bitter ironies that people who work for a more just society are unlikely to become its heirs. Abraham Lincoln signed his name to the Emancipation Proclamation, but it was William Lloyd Garrison’s maligned crusade over the years (he was nearly lynched in Boston by a proslavery mob) that ultimately persuaded Lincoln to dip his pen in the inkwell.

Similarly, Albert Parsons, hanged by the State in 1887 for organizing against harsh working conditions, is familiar only to historians—yet his leadership in the late 19th century labor wars centrally shaped working-class consciousness and its offspring, unionization.

The Line of Dissent is “opinionated” in another sense: I’ve chosen subjects who I admire; the book contains no demolition jobs. The fact that my appraisals are mostly appreciative doesn’t mean that I’m a shallow celebrant of anyone who challenges the statusquo. I’ve known a fair number of mutinous types—of people regarded as outsiders—and can testify to the fact that not all rebels are insightful prophets, or even personally likeable; nor am I suggesting that every insurgent or eccentric is, by the mere fact of their oddity, a fount of insight, a guaranteed sage.

I also want to be clear that The Line of Dissent makes no claim to being a broad-spectrum, exhaustive account of the issues and actors central to the time period covered. I make no claim to comprehensive coverage. Any number of rebels and their causes go unacknowledged in The Line of Dissent. (The disability, Latino, and Native American movements are among those most notably absent, though as significant and worthy as the mere dozen I do discuss.) In our segregated society, we tend to interact—for worse, not better—primarily with those most like ourselves. Put most simply, this book is about some of the people I encountered in my own political odyssey and wanted to memorialize—people whose paths I happened to cross and whose views connected to my own.

It would be sentimental to pretend that honoring the ancestors will do them much good. But knowing they existed might calm the apprehension that our own struggles are merely quixotic. I had in mind, too, that their example of going against the tide might prove an antidote to today’s stampede to homogenization. As Audre Lorde reminded us, you cannot transform a culture by accepting its core assumptions—like the still ingrained view that men and women are “from different planets,” or the “patriotic” conviction that we’re divinely entitled to invade other countries under the guise of saving them. At its inception in 1969, the Gay Liberation Front took an oppositional stance against a broad spectrum of mainstream assumptions and institutions: to the inequities of corporate capitalism, the subjection of people of color, global imperialism, and the patriarchal family. From that radical beginning, the gay movement has over the past forty years gradually shifted to the center.

The dominant strategy of its national organizations over the past few decades has been defended by its adherents as “creative assimilationism.” Their focus is on joining up, on gaining access to rather than challenging, centrist institutions like marriage and the military—leaving those bastions of injustice largely intact, giving them, as it were, a clean bill of health. The gay movement’s slide towards the center isn’t a development I’ve been in sympathy with. The emphatic adherence to mainstream morality—which is to say, the values that characterize white, middle-class life—has, in my view, come at the expense of minimizing—or outright disavowing—the innovative questioning of established pieties that had characterized the gay movement at its inception.

Although all of the people I write about in this book were behaviorally part of the sexual minority, most of them were primarily involved with social injustice movements that did not centrally relate to their own lives. Only two of them, in fact, can be said to have invested most of their activist energy to the LGBTQ+ liberation movement (though several others were incidentally involved).

Essex Hemphill’s deepest involvement, for example, was with the Black struggle—he felt it was his color not his sexual orientation that centrally defined and concerned him. Similarly, Barbara Deming, a staunch advocate of nonviolence, was pre-eminently concerned with the plight of Blacks and women—all women, not just lesbians. Karl Bissinger lived with and was devoted to another man, yet his political energy went exclusively to the War Resisters League. None of the three viewed homosexuality as their “primary emergency.”

Their stories provide fresh material for considering a number of interlocking questions that I raised several years ago in Has The Gay Movement Failed? Why has the national gay agenda over the past few decades been so insistently parochial in focusing on gaining access to mainstream institutions like marriage and the military? Why instead has the official movement shunned the more radical features of the community it purports to represent, like the practice (in contrast to the theoretical advocacy) of genuine partner equality, and its opposition to the “naturalness” of monogamy, lifetime pair-bonding, and binary definitions of gender? And why has the straight Left (like the gay mainstream) chosen to remain oblivious to the unique and subversive features of gay life—the insights it provides into gender fluidity and its skepticism about the sanctimonious insistence on combining love and sex?

A byproduct of the straight Left choosing to remain distant from all things “queer” has been the negation of any possibility of radical outsiders binding together to form a substantive alliance. Some of the individuals who appear peripherally in The Line of Dissent—like Christopher Lasch—inadvertently suggest why the straight Left has kept its distance from queer insights and agendas: he (and a multitude of others) insists on the view that maintaining the traditional family—dominant husband, subordinate wife, dutiful children—is the equivalent of Saving the Republic. Lasch and other straight radicals, moreover, have been unaware—or unwilling to acknowledge—that in the past, gay lefties have sometimes been involved, admittedly peripheral, in social protest movements other than their own: Sylvia Rivera’s support for the Black Panther movement, Barbara Deming’s early activism in anti-nuke demonstrations, Naomi Weisstein’s challenge to the profound discrimination against women in science.

To a limited extent, radical gay/straight alliances did materialize in the creative decade between 1965-75, but they fell victim to the country’s post-1975 mud-slide to the Right. Today, thanks to a new generation, such connections are once more emerging. Only time will tell if they’re any match for the infinitely more powerful cartels that currently control economic and political life.*

Substantive social change typically originates from the margins, not the center, and those who vocally deplore “things as they are” are often derided as dangerous cranks—as peddling views and leading lives that threaten established authority or orthodox morality. Yet over time those same radical views often become both legible and persuasive to a later generation. Some even achieve majoritarian acceptance—though rarely in time to save their originators from calumny in their own day and oblivion thereafter.

Find out more about The Line of Dissent here.