Meet the author: Cary Alan Johnson

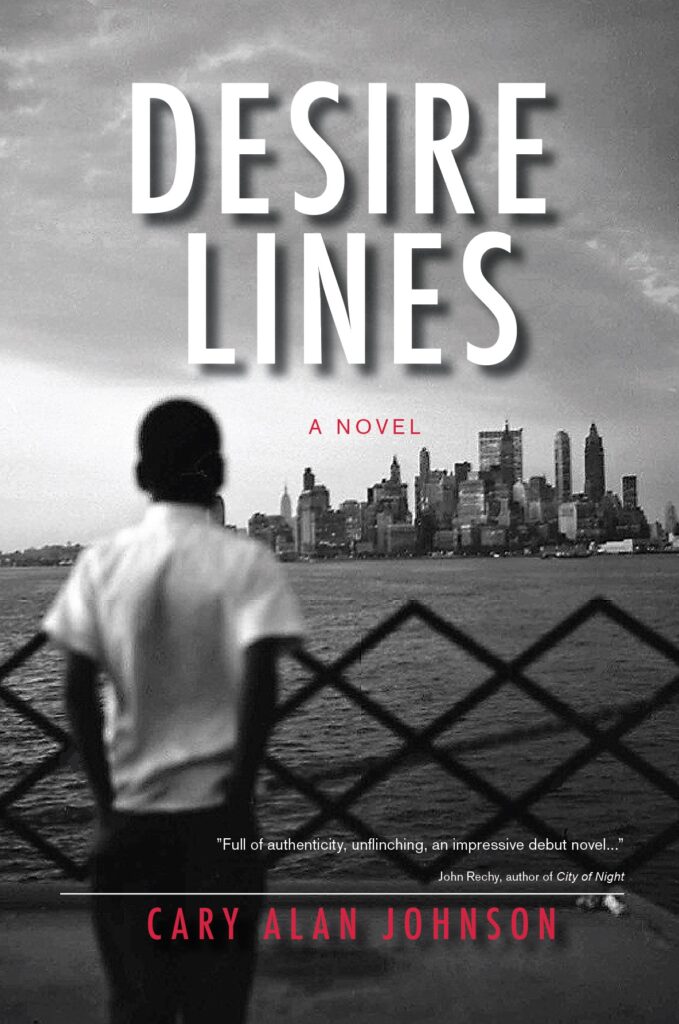

Cary Alan Johnson’s debut novel Desire Lines comes out September 6 and Stephanie Grant delves into his world with this interview.

In Desire Lines, a Black teenager growing up gay in Brooklyn is captivated by a vision of life on the other side of the river, where the sparkle and glitter of Manhattan beckon. Coming into adulthood, he finds himself living in a five-floor walk-up in Hell’s Kitchen just as the AIDS epidemic is hitting the city. We follow him and his group of friends as they experience the first wave of illness and death, and then accompany him on a two-year journey to Zaire, Central Africa, where he must confront corruption and homophobia in new and unexpected ways. Back in New York, he and his best friend—a biracial straight woman—try to find their place in a rapidly changing and increasingly perilous city that threatens to destroy first their friendship, and then the narrator himself.

Stephanie Grant: I know from our conversation that the novel is autobiographical or semi-autobiographical. My first question then is why a novel and not a memoir? We are living in a kind of golden age for the memoir – so many folks are writing them, myself included. What did the novel offer you that memoir didn’t?

Cary Alan Johnson: Desire Lines started out as a set of essays, something approaching a memoir, about the Black gay experience, until I decided it was coming off too preachy. So I shifted to fiction. Is it autobiographical? Semi, certainly. I borrow from my experiences growing up in Brooklyn, serving in the Peace Corps, and coming of age in New York in the wacky, dystopic mid-80s. The book deviates enough from my own life that memoir was not the right form. Maybe I’m lazy or don’t yet have the literary chops to write a memoir that provides the substantial rise and fall that most readers expect in a book, but that’s still honest and credible. Life aint like that. It meanders, backtracks, and surprises in inconvenient ways. Sometimes life is just plain boring, except perhaps for readers of similar profiles. I wanted Desire Lines to interest a wide variety of readers based on a set of universal experiences or feelings. A novel seemed an easier and truer format. Once my narrator started speaking to me in his own voice—a voice which was at the same time mine, but also decidedly not mine—I knew that the book needed to be fiction.

I know you as a writer of poetry more so than prose, although of course you’ve published stories and essays as well. The novel is perhaps the most capacious literary form – it allows for almost endless expansion: I’m thinking of the recent international sensations, Elena Ferrante’s 3 Neapolitan novels and Karl Ove Knausgaard’s 7-volume My Struggle. But poetry is all about compression and distillation, offering acute moments of perception and experience. What was the transition like for you as a writer to move into this form?

Johnson: The transition from poetry to short stories and then to longer-form prose felt natural and necessary. I stopped writing poetry many years ago. It felt like too truncated a form for me. I was writing short stories for a while, and I like that form. But embarking on a novel is an ambitious and badass undertaking, for any writer. But once I got started writing this book about ten years ago, I knew that I had to finish and do the equally challenging work of getting it published, marketed, purchased and read. It’s my love letter to the 80s, to the many men and women we lost to AIDS and addiction, a loving nod to the survival of my generation and to our future as elders.

Can you talk about your writing process and how the novel form changed it?

Johnson: There are just so many words, sentences, and paragraphs in a novel, and you’ve got to get them right—precise, honest, and clean. My writing process has varied over the last decade. At several points I took fiction classes and workshops where I was able to develop chapters of the book with an instructor and a cohort. These were hugely important to my process and to making progress. In the end, however, it was me in front of my computer at 6 every morning, writing and editing before I had to go to work.

Your prose is lyrical. The descriptions of the physical world here are deliberate, concrete, yet often lush and musical. There is a tension in every piece of writing between the lyric and the narrative – were you aware of this tension writing Desire Lines? Did you find yourself noticing when you leaned into the lyrical? When you focused more on the demands of narrative?

Johnson: It was a struggle. The first drafts of the book were overly poetic, and I had to tone that done through cutthroat editing. Many dead darlings. As you’ve just mentioned there is a line between the lyric and the narrative, and the line is different for every reader. I enjoy some of the lush, poetic language in the book, but there also needs to be a driving story. I don’t enjoy reading prose that’s too sweet in terms of the language that’s used to convey the plot. I need a solid, driving storyline with perhaps some flowers strewn along the path. I want to read a book that moves me along a path of a storyline, and occasionally moves me with a beautiful sentence or a stunning paragraph. That’s what I tried to achieve in Desire Lines, not so much in the writing, but in the editing.

At times the novel has a sociological feel – which is to say, you’re providing a map of queer life in NYC in the 80s. You map the “geography of the subway bathrooms” for instance. Can you talk about why it was important to include this geography in this particular novel?

Johnson: The book is as much about New York in the 80s as it is about anything else. There are lines that the narrator traces through the various neighborhoods, from Brooklyn, to Chelsea, the NYU campus in the Village, Spanish Harlem, the Bronx, and back. There are a lot of scenes that begin or end with going into or coming out of a subway, because frankly that’s how life in New York gets divided up. And without being overly symbolic, the title, Desire Lines, really does speak to the unmarked paths and unmapped roads we travel in pursuit of desire of various kinds.

The narrator of Desire Lines is smart and sexy and likable. I found his coming out and his coming into political consciousness absolutely riveting. Yet he also behaves badly at times. Leaving Zogby when he knows he’ll likely die of AIDS before he returns from the Peace Corps. Can you talk about the decision to include the narrator’s own ugliness? Were you ever tempted to sanitize him?

Johnson: Clean, simple characters tend to bore me. I hope my narrator is lovable exactly because he is flawed. His internal dishonesty grows as the novel progresses. The trick, I suppose, is to ensure that he is not such a huge liar or in so much denial that the reader grows exasperated. He does have flashes of clarity about what a mess his life is becoming and how bad choices many of his choices are. But he manages to justify all kinds of outrageous bullshit, until he just can’t lie anymore—to himself or to others. I did think a bit about how self-confident he should appear on the page. I didn’t want him to come across as overly full of himself. I tried to infuse him with an ample amount of self-doubt.

At some point during the narrator’s affair with Augustin, the narrator tells us: “He has something that I want—his Africanness, his sweet simple comfort in his blue-black skin. I want to share in it with him.” I love this because I think there is often something we want in sexual encounters that has little to do with sex but has everything to do with who the other person is and who we aren’t. Very early on we get the wonderful line: “It’s funny how we all seem to crave the man we want to be.” Can you talk more about this kind of desire that so often accompanies or fuels sexual desire?

Johnson: Desire is a singular, exquisite, and sometimes damning emotion. And so misunderstood, so oversimplified, so trivialized. (A lot like the way in which we think we understand disgust, but perhaps do not, the theme you handle with so much style in your new memoir.) We take a lover for so many different reasons. Regina, the narrator’s biracial best friend, choses her men to challenge her White father and what she thinks he wants from her. The narrator has sexual desire for Augustin certainly, but what’s at the heart of it. His desire is really to belong to something that Augustin takes for granted, his desire is as much cultural as it is erotic. In my own life, sometimes I’m as attracted to a man’s family, his apartment, his circle of friends, as I am to him. Those things are part of his identity. I crave in others the things I most love and/or lack in myself.

There is a lot of shame in the book. So much of it seems to revolve around not being enough of something – masculine enough, black enough, good enough. When Augustin’s family is trying to end the affair, the narrator tells us: “shame . . . was both the method and the ultimate intent.” Which I found just brilliant. Can you talk about that – method and intent?

Johnson: Steph, you chose to focus on the singular emotion of “disgust” in your recent memoir. If I were to write a memoir, it would likely canter around “shame.” So much of my youth was spent living in, and responding (poorly) to, the shame that I was experiencing. And I think we know—especially Black people know—that people who love us install shame into our lives as a way of protecting us, to keep us in line and away from the horrors of racism and misogyny. In describing the narrator’s relationship with Augustin, I was specifically writing about the deployment of blackmail against a same-sex couple who faces exposure and worse in a homophobic African country. Blackmail is an awful tool, but highly effective at policing queer behavior. It uses fear of exposure (shame) to reinforce self-hatred (shame). It’s a great big ole shame-fest. It adds to the narrator’s sense of social and cultural dislocation. But it also makes him angry—which is a good thing. How dare people use our intimacy as a weapon to control us!

There are different kinds of shame in Desire Lines which got me wondering about the differences between the shame the world imposes – the effects of racism and sexism and homophobia – and the shame that feels more existential. The shame we seem to come with. Do you see these as distinct? Or I am I projecting my own ideas onto your novel? Can you talk about how these different shames coexist within the narrator?

Johnson: I want to believe that there is nothing existential about shame, at least if I am understanding your point correctly. I don’t think we are born with any of that crap. Babies are born shameless. They want what they want when they want it. But almost instantly the world starts to tell us to be ashamed of what we want. That we shouldn’t want or expect to have all of our desires met. And like I mentioned earlier, a lot of the installation of shame in our psyches is good intentioned. Black parents wield shame as a way of protecting their children. Don’t be too visible. Don’t expect too much. Don’t think you’re so special. It’s their way of helping us to calibrate our expectations in a racist world that doesn’t love us the way that they do. Once you add the shame—both internal and externally imposed—of homophobia, a toxic stew is cooked up. As an adolescent, my narrator feels shame for being Black and for being a sissy. This ignites in him a desire for the same boys that bullied him. We learn to desire our tormenter, and that just multiples the shame. It’s quite the vicious cycle that only a lot of therapy or other types of introspection can help us to address.

Desire Lines takes on so much – Black queer identity, the AIDS crisis, sexual violence – but also addiction. And, specifically, crack addiction. The scene of the narrator’s final encounter with Sammy, his drug dealer, was harrowing. Can you tell us about writing this scene, what it required of you?

Johnson: That was a hard scene to write, but one which I couldn’t shy away from. There is so much writing about sex in the novel, that I felt compelled to write about sexual violence as well. Also, what does it mean when the violence is perpetrated by someone for whom the victim has had genuine desire? How does that add to the shame? There are a couple of places in the story when the idea of consent is interrogated. Who is allowed to desire? Who is denied the right to consent? A teenager? Someone who is drunk or high? Someone who is desperate for money or survival? I think in our current moment of wanting to do better around protecting people from sexual violence, these questions are posited as black and white. And perhaps that’s correct in the moment. But they still need honest exploration.

As the novel starts to wind down, there is a shift toward understanding Regina’s estrangement from her family, in particular her father. We don’t get the rapprochement with the narrator’s family of origin – except by inference. It’s a very interesting choice. Can you tell us why you shifted here?

Yeah, that’s so true. And I noticed that as that chapter was coming together. I asked myself, why does Regina get certain resolutions around family issues when the narrator doesn’t, or at least not to the same extent. I guess my answer is, that’s life. Sometimes other people solve their problems, and you support them in that experience. Life aint neat. Everything doesn’t wrap itself up nicely the way it so often does in theatre, novels, or film. Shit remains messy, but change is always possible. I tried to show the possibility of the narrator’s rapprochement with his family and history through a scene late in the book between him and his brother. But even Regina’s possible reunion with her father could still go terribly wrong. Nothing’s set in stone. It could all still go bust. Or we could all find the peace that we are looking for.

Also, sometimes in our lives, other peoples’ development (and, sadly, dissolution) can be a proxy for our own healing. If a friend heals their relationship with their parents, that gives me hope. If another friend finds themselves in financial straits, that serves as a cautionary tale for me. I identify with other peoples’ joy and pain and that helps me to heal my own relationships, even if it’s with baby steps.

Regina is a spectacular character. Like the narrator, there are things we love about her and things we don’t. I think many novelists struggle to portray secondary characters with the same complexity they lavish on their protagonists. Was it challenging to write Regina so complexly? Here you are writing across gender – did you worry that showing us her human frailty would get you into trouble?

Johnson: You may notice that the book is dedicated to Regina, even though she’s a fictional character. She’s an amalgam, really, of all the women with whom I’ve had tight, healing, victorious friendships. I think that’s why I made her biracial. It’s an acknowledgement that I’ve had intimate friendships with women of all races. The character of Regina morphed a lot during the years I spent writing the book, whittling her down, cutting the lines of dialog that she would never say and listening to her whisper in my ear the things that she truly would say. Regina has her own trauma, for sure, and her own insecurities, but she does a better job of managing them than our hero. She’s sexy and sassy, but also wounded and afraid. And she’s got a secret.

Desire Lines feels like the beginning of the narrator’s story. Are you working on another instalment? What’s next for you in your writing life?

Johnson: Though I take solace in knowing that Baldwin needed ten years to write Go Tell it on the Mountain, it took me even longer to finish Desire Lines. Then again, I was working a series of full time jobs, and I’m just not a fast writer. Now that it’s finished, I want to devote my energy to promoting it and ensuring that it gets into the hands of its intended audience—Black gay men and the people who love us. I’m grateful to Don Wiese and Chuck Forester at Querelle for publishing the book, but I recognize that they are a small press that don’t have the same resources for marketing enjoyed by the big publishers. I want to see what kind of reaction the book gets and what people (hopefully) like about it. These may help me decide on my next project. That said, I’ve got a few ideas kicking around in my head. I’d like to bring what I’ve learned about character development to telling more stories about gay men in middle age and also about Black Americans in Africa. Writing Desire Lines taught me that the novel, as a form, is a beast. But it can be tamed—with time, perseverance, and brutal honesty.

About the interviewer

Stephanie Grant is a writer and teacher of writing. She grew up outside of Boston, MA. She received her BA from Wesleyan University, CT and studied creative writing at New York University. Grant has taught writing at The Ohio State University, Mount Holyoke College, and American University in Washington, DC where she currently directs the MFA Program. She is known for fine-grained teaching of craft, ranging from narrative arc to sentence structure, and is available for guest workshops.

Cary Alan Johnson is having a book tour!

9/7- The Tenth Magazine and Khary Septh Hudson, NY 7:30pm

9/8- Greenlight Books, Brooklyn NY 7:30pm

9/12- Franklin Park Reading Series, Brooklyn, NY 7:00pm

9/13- Giovannis Room, Philadelphia 6:00pm HOST Sabrina Vourvolias

9/19 – Fabulous Books, SF 7pm HOST Brontez Purnell SPONSORS Aids Project of the East Bay

9/21- Bureau of General Services/Queer Division, NYC 7pm

Paradise Regained: Black Queer Writers Read (in person and live-streaming) at 7:00 PM – 9:00 PM

Three Black gay writers, each of whom released a new book in 2022, gather for a fierce read. Hosted by the inimitable Pamela Sneed. Featuring Jafari Allen, David Ambrose Jackson, & Cary Alan Johnson.

This event will take place in person at the Bureau of General Services—Queer Division, on the second floor (room 210) of The LGBT Community Center, 208 W. 13th St., NYC, 10011.9/23 – Charis Books, Atlanta 7:30pm HOST Craig Washington

https://www.charisbooksandmore.com/event/desire-lines-cary-alan-johnson-conversation-craig-washington