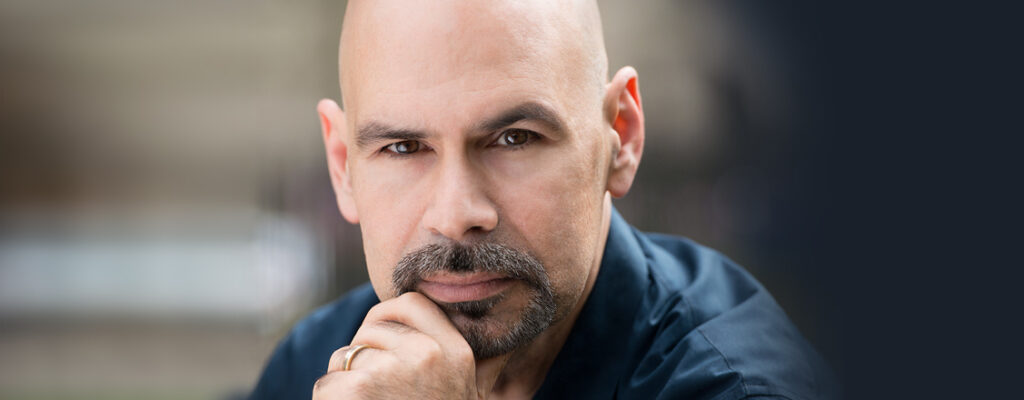

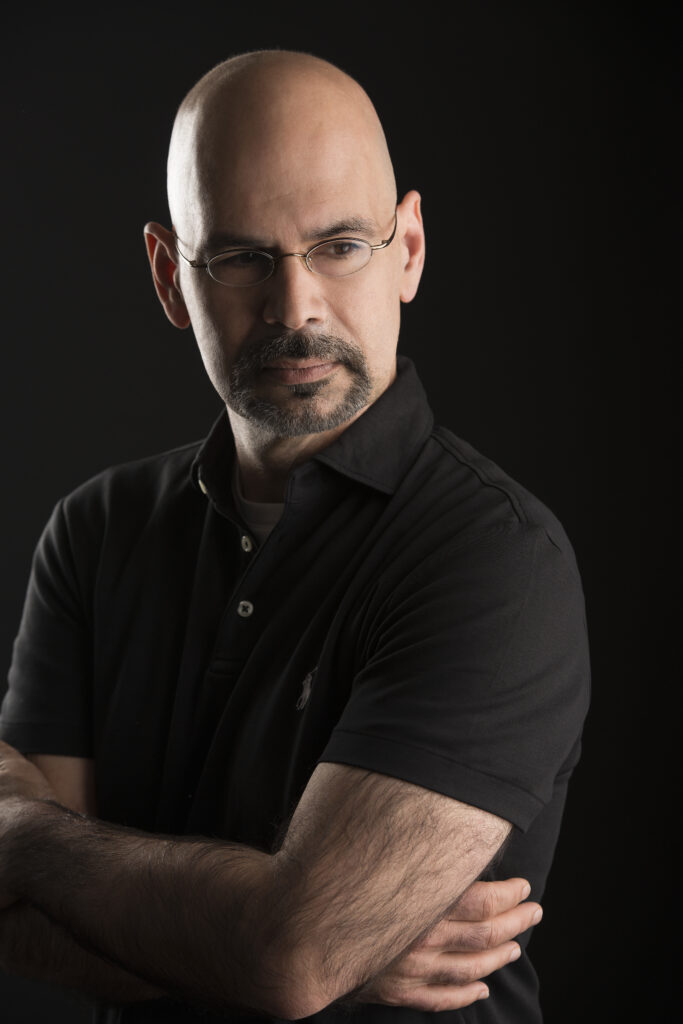

Meet the author: Orlando Ortega-Medina

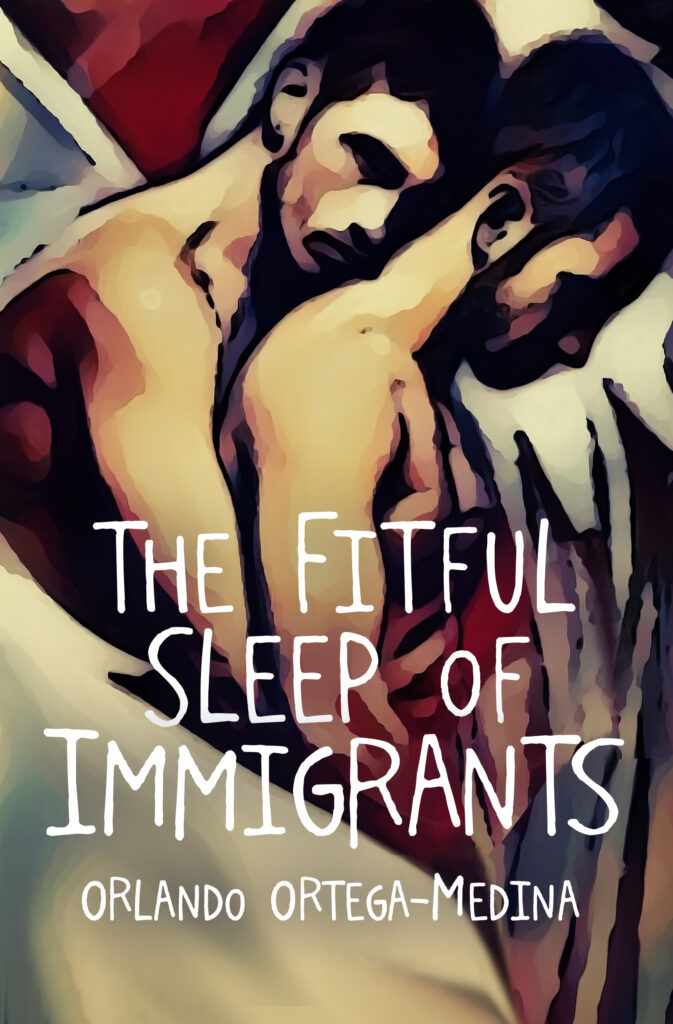

Award-winning author and immigration attorney Orlando Ortega-Medina returns with The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants, out on April 18 from Amble Press, a powerful family drama that plays out within a captivating legal thriller.

Inspired by events that forced the author and his partner to emigrate from the United States because of marriage inequality, this novel is an extraordinary and timely tale about the value of family and friendship, loyalty and love in the face of adversity.

It’s the 1990s in San Francisco and Attorney Marc Mendes, the estranged son of a prominent rabbi, is a burned-out lawyer with addiction issues. He’s plotting his exit from the big city to a more peaceful life in idyllic Napa Valley, but before realizing this dream, the US government summons his Salvadoran life partner Isaac Perez to immigration court, threatening him with deportation.

As Marc battles to save Isaac, his world is further upended by a dark and alluring client who aims to tempt him away from his messy life. Torn between his commitment to Isaac and the pain-numbing escapism offered by his client, Marc is forced to choose between the lesser of two evils while confronting his twin demons of past addiction and guilt over the death of his first lover.

We caught up with the London-based attorney and writer to find out more about his fascinating and gripping novel.

You have written three novels and one short story collection. The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants feels like it might be your most personal in some way. How is it inspired by your own experiences with US Immigration? What was your situation and what is the status of it now?

Ortega-Medina: The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants is my most personal work, to be sure, given that the main character Marc Mendes, like myself, is a US-born lawyer, who practiced law in San Francisco in the late 1990s. My professional experience with US immigration law was as an immigration lawyer, representing clients in deportation cases before the US immigration court. On the personal side, my experience with the system was as someone in a romantic relationship with another man who was in the states on a grant of temporary asylum. Unlike the characters in the novel, my partner and I chose to leave the United States rather than sit around for years waiting for him eventually to be called to a hearing he wasn’t guaranteed to win. We’re now permanently and happily settled in England.

You dedicate the book to the countless multinational same-sex couples who are forced to emigrate due to marriage inequality. Do you and your partner plan to return to the US?

Ortega-Medina: I think not. Once we tasted life outside the US, including the liberal social policies we were seeking, there was no going back for us. That said, we do love visiting the US once a year to spend time with family and close friends.

Do you identify with the character of Marc Mendes…or where does he come from as a creation of fiction? He feels to me to be at the intersection of many identities…

Ortega-Medina: I do identify with Marc – as an exaggerated alternate-universe version of myself. That said, I’m not Marc, and many of his missteps I am fortunate to have avoided.

Now why set it in the 1990s? I’m wondering if this reflects your age and experience or if you chose this decade for thematic purposes…and hooray, no cell phones, which somehow destroy procedural narratives.

Ortega-Medina: I like to set most of my stories in the age just before the advent of smartphones and social media to limit access and communication between the characters. In my view, such limitations tend to build more tension into a narrative. For example, if one character needs to speak with another character and has no quick access to a telephone, they must wait. And, waiting is never easy. That said, I did actually include a basic cell phone in The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants given that most lawyers carried them in the 1990s to stay in contact with their offices. Sorry!

What is your perspective on how the UK is handling immigration vs. the US – I’d be grateful for any observations or overarching comments given that it is a hot button again in the US.

Ortega-Medina: No system is perfect. The UK is better at some things than the US and vice-versa. My main gripe with the immigration debate in the United States is that it is eminently more race-focused than in the UK to a fault.

What do you feel is the most commonly held misconception in the US about immigrants and what is your personal and professional view of it as an issue that is not going away and that politicians continue to exploit or mishandle?

Ortega-Medina: The most commonly held immigration-related misconception in the US is that illegal immigration originates exclusively from south of the border. As such, the overwhelming focus of anti-immigration hostilities is against the Latino population. The truth, however, is that there are significant numbers of illegal migrants living and working in the United States from both Canada and Europe. I’m referring here to individuals who enter the country legally and then overstay and continue to live and work in the USA under the radar. Nobody pays any attention to them because they easily blend in with the white population. As a result, Americans tend to have a skewed perception of exactly what is going on when it comes to “illegal migration”.

When you were at UCLA studying literature, what were some of your literary inspirations and influences? Your prose style is clear and colorful and expedient in a good way! It’s a little bit Chandleresque, but please elaborate. The noirish element I am picking up from the love triangle dynamic and the possible criminality of Silva – also Marc’s own bete noir of addiction…

Ortega-Medina: My most significant literary influence when I was at UCLA was the Japanese author Yukio Mishima (in translation), starting with his seminal novel Confessions of a Mask (running a close second was Junichiro Tanizaki’s novel Some Prefer Nettles). I loved Mishima’s daring, confessional first-person prose, in the style of the Japanese “I-Novel,” as well as the dualities that obsessed him and informed many of his later novels. In my early work, I stroved to emulate the style of the Japanese “I-Novel” which are semi-autobiographical works where the line between the main character and the author is blurred. Your readers can find examples of this in my first book Jerusalem Ablaze: Stories of Love and Other Obsessions, which includes an homage to Mishima titled “Torture by Roses.” In my new novel The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants, I tried something different. In effect, I melded an “I-Novel” in which Marc Mendes is both the main character and narrator, together with a familiar noir trope (the homme fatal) in the character of Alejandro Silva. Silva relentlessly pursues Marc as he navigates a series of personal and professional crises. This collision of genres ratchets up the tension and drives forward the narrative at a quicker pace than in a traditional “I-Novel.”

For aspiring fiction writers – especially queer and marginal voices – what are some words of advice to someone wondering or doubting if their idea for a novel is strong enough?

Ortega-Medina: Don’t be afraid to tell your story! Write with confidence and believe you’re composing the best book ever written. Most importantly, once you start writing your story, make sure you finish it. To this end, and on the practical side of things, my advice is that you fully flesh out your story from start to finish in the form of an outline and scene list. When the initial outline and scene list are complete, have these evaluated by an editorial expert or a couple of trusted readers. Once you have an internal green light on your story, get to work on developing your main characters independent of the narrative. Get to know them inside and out; have them interact with each other in test scenes. Then, armed with your outline, scene list, and character studies, get to work on the actual writing of your novel. If possible, write every day consistently with one day off. Don’t worry about mistakes or clever turns of phrase and don’t look back at anything you’ve written until you get to the end. Once finished, set aside your draft novel for at least a month before reading it through and commencing the all-important revision process.