Our place at the table: Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer exhibition

Curator Kenny Fries writes about queer disability, and an exciting new exhibition.

I am accustomed to being the only queer disabled person in the room. Most of the time, in queer spaces I’m the only person with a disability, and when in a disabled space, I am the only queer. As used to these situations as I’ve become, sometimes this situation is untenable.

In 2015, at the large and important “Homosexualy_ities” exhibit at the Deutsches Historisches Museum and Schwules Museum in Berlin, there were inaccessible places in the exhibit where my wheelchair could not fit. The exhibit texts were too high on the wall for me to read. I was at a groundbreaking (and government-funded) exhibit and I could not completely access it. Worse, there were only two minor representations of disability and disabled persons in the entire two-museum exhibit.

When I was invited to read for the only English language event on the exhibit schedule, before I shared my work I figured I should say something about the inaccessibility and lack of disability representation in the exhibit. Birgit Bosold, one of the exhibit’s curators, was present, and because of what I said, she realized something had to be done about this. When the exhibit moved to Münster, some disability representation was included.

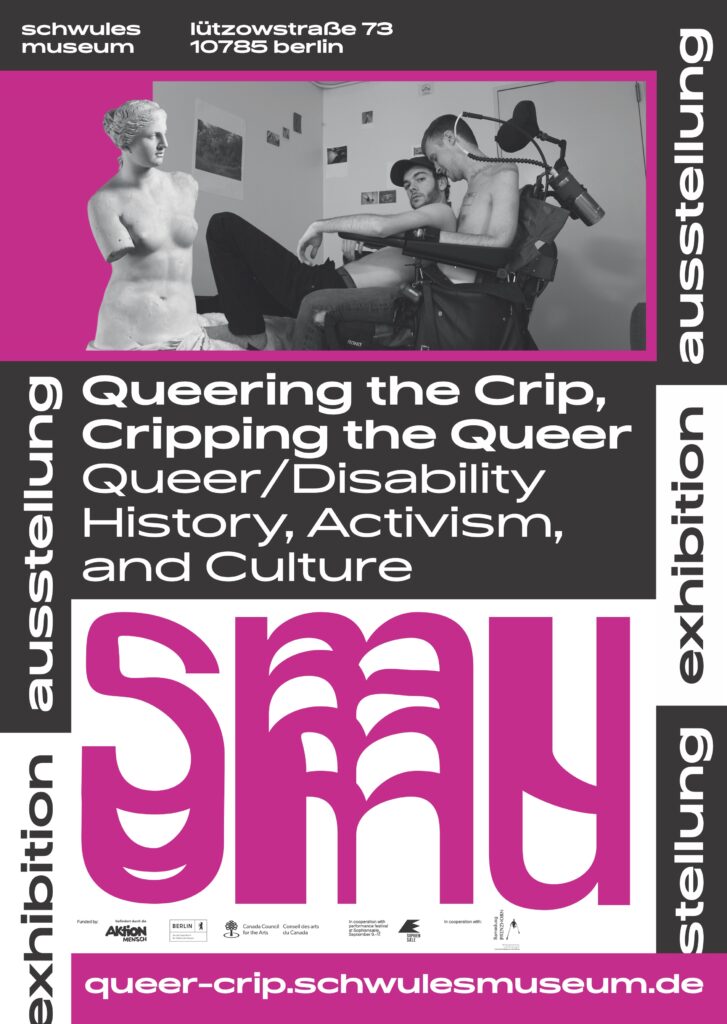

More importantly, the conversation I had with Birgit led to our curating “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer”—the first international exhibit on queer/disability history, activism, culture, now running at the Schwules Museum Berlin. The exhibit (the title comes from U.S. disability studies scholar Carrie Sandahl) includes the work of nine U.S. artists, along with 14 other international artists, and this work is presented in a historical context along with historical objects.

Access at “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” was essential to both the content and design of the exhibit. Perhaps more importantly almost all of the artists identify as both queer and disabled. Though I am the only queer/disabled person on the curatorial team, the other team members are either queer or disabled. In this position, and because the idea of the exhibit was mine, I had to hold both the queer and disabled perspectives to guide the exhibit’s curation.

Often, I was asked to explain how certain queer parts of the exhibit related to disability. For example, the exhibit includes the work of HIV+ U.S. artists Charles Ryan Long and Brontez Purnell.

How does HIV historically relate to disability? Because of my experience living in San Francisco at the peak of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and early 1990s, I knew how many with HIV learned from disabled folks about how best to navigate the government and medical bureaucracies to get the assistance they needed. I also knew firsthand how disability, historically a symbol for mortality and death, now encompassed those with HIV.

Similarly, I was able to make the connection between the “ugly laws,” which banned disabled people from being in public, that were omnipresent in the U.S. in the latter 19th century (the last “ugly law” wasn’t repealed until 1974), with Paragraph 175, the German anti-homosexuality law. Paragraph 175 was ostensibly to protect younger men from the “predation” of older men. But case histories show it was the offense to public morals that was actually the main offense. Thus, both disabled people and gay men were prohibited by law to offend public morals.

I also personally felt how the writing of Audre Lorde, especially in The Cancer Journals and in A Burst of Light, brought together not only the queer and the disabled. That Lorde had spent time in Berlin, and was an important figure to the Afro-German and German feminist movements, made her an essential part of the exhibit.

It was fortuitous that Birgit, my co-curator, and our researcher Sydney Ramirez, found in a 1984 interview, something Lorde said about a feminist book fair in London “held in a room that was inaccessible to disabled people.” Lorde noticed, “At the bottom of insurmountable steps, a petition was passed around expressing a complaint about it.” She was concerned “that so many women did not sign it.” Lorde observed this “and wondered why they would even want to participate in a feminist book fair.” She asked: “What are they trying to find out here if they already can’t see such a connection? This was a book fair that was not accessible to women with walking disabilities and all they were supposed to do was take a stand and put their name down.”

In the interview, Lorde goes on to say that this situation “could only happen because there was no disabled woman in the preparatory committee and therefore the question simply did not come up. What matters to me is that we broaden our awareness in such a way that no disabled woman or black woman needs to be in the preparation group for this.”

I strongly related to Lorde’s prescient words. On numerous panels, juries, and committees, I’ve been the only disabled and/or queer person at the table. At countless readings, bars, and conferences, I’ve been the only one present, as well.

Representing queer disability

As important as physical access is, what is often forgotten is the cultural representation of disability, and especially queer/disability. Though queer/disability stories can be found as early as ancient Greece (the blind prophet Tiresias lived as both a man and a woman during his mythic lifetime and is often depicted as gay, non-binary, or as a woman, in many productions of the Oedipus plays) it is not usual to encounter our stories in museums, theaters, or in our literature.

Even during the Nazi Reich in Germany, when both queers and the disabled were persecuted, sterilized, and murdered, stories about queer/disabled people during that time are not easy to find. In the exhibit we highlight two such stories, most importantly that of Hans Heinrich Festersen, who was hanged at Berlin’s Plötzensee prison in 1943, and whose letters written from prison to his sister Ruth are in the archive of the Schwules Museum.

The queer/disabled artists, and the queer/disability stories we feature in “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” are really just the tip of the iceberg. The exhibit offers many avenues of research and art to pursue in other exhibits, formats, and venues.

When Nina Mühlemann, a Swiss queer/disabled performer, scholar, and activist, came to “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer,” and texted that me that the exhibit was “so us,” I knew we had created a welcoming and inclusive space that I had longed for but had not yet experienced.

But Lorde’s words remain. Would this have happened if there was not a queer/disabled person with agency in the room?

About the Author

Kenny Fries is the curator of Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer, the first international exhibit on queer/disability history, activism, and culture. He is the author of In the Province of the Gods (Creative Capital Literature Award); The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory (Outstanding Book Award, Gustavus Myers Center for the Study of Bigotry and Human Rights; and Body, Remember: A Memoir. His current work-in-progress is Stumbling over History: Disability and the Holocaust, excerpts of which have been in The New York Times, The Believer, and Craft, as well as featured in his video series What Happened Here in the Summer of 1940? He is a 2022 Disability Futures Fellow of the Ford Foundation and Mellon Foundation.

About Queering the Crip

Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer, at the Schwules Museum Berlin until April 30, 2023, is the first international exhibit to explore the multiple historical, cultural, and political intersections of queerness and disability. The exhibition counters the fantasy of “the ideal body” with artworks by over 20 international contemporary artists, including nine queer/disabled artists from the U.S. By juxtaposing historical objects with contemporary drawings, paintings, photographs, mixed media installations, performance videos, and audio works, curators Kenny Fries (U.S.), Birgit Bosold (Germany), and Kate Brehme (Australia), highlight how queer/disabled artists reclaim the historical narrative with agency and pride.

The U.S. artists in the exhibit include Justin LeBlanc (Chicago), Riva Lehrer (Chicago), Charles Ryan Long (Chicago), Perel (New York City), Brontez Purnell (Oakland), Joey Solomon (New York City), Kah Mendoza Weethee (Los Angeles), Quintan Ana Wikswo (New York City), and the late Mel Baggs. Some works were especially commissioned for the exhibit, including U.S. artist Riva Lehrer’s Zoom portrait drawing of German queer/disabled artist and activist Steven Solbrig, whose photographs are also included in the show. A section of the exhibit showcases queer/disabled artist icons Lorenza Böttner, Raimund Hoghe, and African American writer Audre Lorde. Another features queer artists living with HIV.

According to U.S. disability studies scholar Carrie Sandahl, who coined the phrase of the exhibition’s title, sexual minorities and people with disabilities share a history of injustice: “Both have been pathologized by medicine; demonized by religion; discriminated against in housing, employment, and education; stereotyped in representation; victimized by hate groups; and isolated socially, often in their families of origin.”

The exhibition is curated by queers and people with disabilities; the contemporary artists exhibited largely self-identify as disabled and queer. Sandahl points out, “Those who claim both identities may be best positioned to illuminate their connections, to pinpoint where queerness and ‘cripdom’ intersect, separate and coincide.” Art Agenda says, “both groups have managed to carve out rich and often joyful cultures in the face of oppression—as evidenced in this groundbreaking exhibition.”

With audio guide, a Sign Language video guide, texts in multiple languages (including simple language), tactile models, a tactile floor guidance system, transcriptions of audio works and subtitles of video works, the exhibition enables all visitors to experience the exhibition as accessibly as possible. Furthermore, the Schwules Museum will use the barrier-free museum entrance for all visitors starting with the opening of “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer.”

U.S. curator Kenny Fries says, “The commitment to full access is a “must have” for most cultural institutions today. However, this rarely means anything more than having ramps or band-aid guidance systems available. Real participation, necessitates that queer people with disabilities co-shape culture as artists, curators, museum and theater directors, critics, editors and publishers.”