Pandemics, power, and the history of queer bodies

Naomi Wolf’s latest book is a celebration of queer identity and a battle cry in defense of our civil liberties.

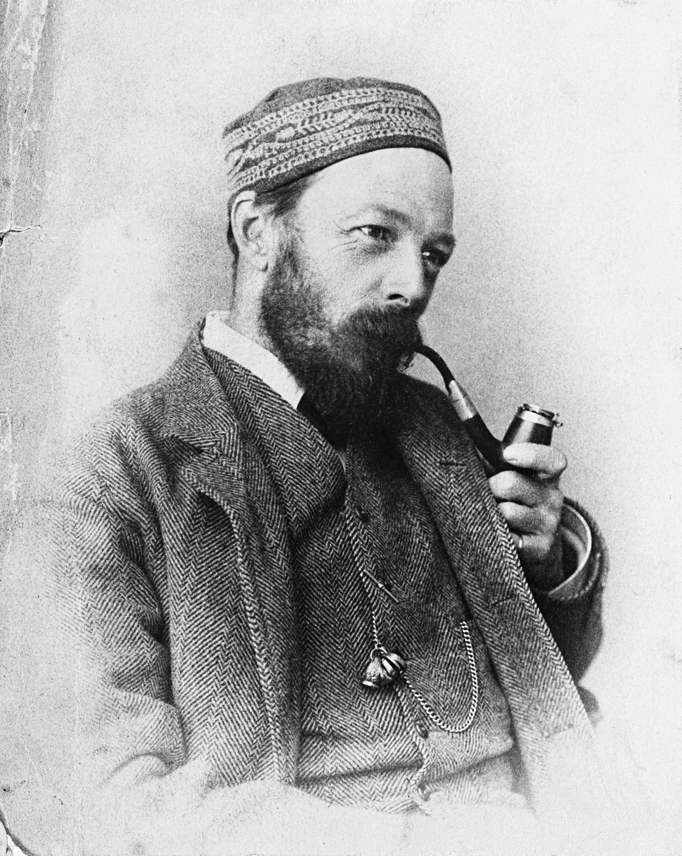

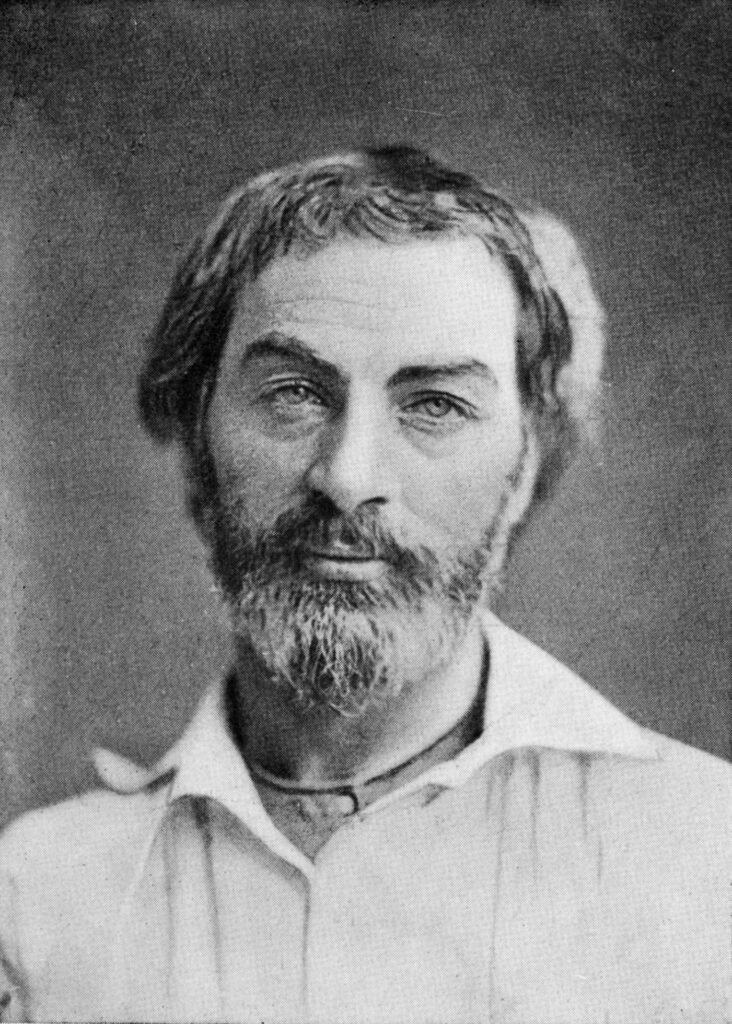

In her latest book, Outrages: Sex, Censorship and the Criminalization of Love, the New York Times best-selling author of the Beauty Myth makes an inquiry into the abuses of state power in Victorian England around the freedom of gay men, specifically the life of the poet John Addington Symonds. A contemporary and admirer of Walt Whitman, Symonds was, according to Wolf, the grandfather of the modern gay rights movement, penning a manifesto that argued for the acceptance of same-sex love.

For our edification, Symonds’ gay identity is manifest in volumes of letters, beginning in his teenage years when he fell in love with another boy. This desire persisted throughout his life, sometimes cloaked in Hellenic code, other times directly expressed in a manifesto and a memoir that were published after his death. Symonds wrote A Problem in Modern Ethics (Being an Inquiry into the Phenomenon of Sexual Inversion, Addressed Especially to Medical Psychologists and Jurists), and Wolf’s scholarly attraction to the subject matter mirrors her own interest in the cultural value of queerness.

“I identify as a cisgender woman, she/her, and in terms of my orientation I don’t think I have the right to call myself a queer woman,” she tells me, “but at the same time, it’s a longer conversation: I don’t think ‘straight’ is adequate as a label. I’ve written in Promiscuities and Vagina about sexual fluidity, even though that term wasn’t current when I wrote those books, so if I had to choose a word, [queer is] the one that I am most comfortable with. At the same time, most of my life has been with men, so I don’t think I have the right to identify myself as a member of the queer community.”

And yet she feels invested in the historic struggles of the queer community because they are one of the demographics that endure state-sponsored censorship and the violations of personal freedoms at the hands of governments around the world. Wolf researched and wrote Outrages long before the coronavirus pandemic plunged people’s lives everywhere into some for of restrictive living, but its analysis of 19th century queer bodies, the development of public health and sanitation, and the intervention of the Victorian state in queer and female sexual behaviors through legislation and surveillance, has some eery parallels with today.

“I’m not claiming to know what it’s like to be a gay man in the 19th century, I don’t think anyone can know what it was like,” says Wolf. “But John Addington Symonds narrated his own inner life very extensively. He was a memoirist and he wrote secret homoerotic poems and love poetry that he had to publish with the pronouns changed. He wrote biographies of men that today we would call gay men…he exhaustively tried — and that’s partly why I was drawn to him—to write about censorship. And I’ve written about censorship my whole career. This book isn’t just about a gay man. As amazing as Symonds is, the themes of this book are the same things I’ve been writing about since 2007, which is the state suppressing speech and invading our personal lives and deciding who we can sleep with, who we can love, what gender we’re supposed to be, and how we can identify ourselves.”

Wolf sees Outrages as a continuation of her book The End of America, which argued that America was on its way towards a dictatorship model of government, employing tactics such as torture, suppression of the press, private militia, arbitrary detention and other tactics to maintain state power. As an example of such tactics today, Wolf cites the “techniques that have been refined on the bodies of members of the LGBTQ community” to “industrially produce hate,” including the anti-trans hysteria that proliferated under the Trump administration.

Wolf, who was an adviser on women’s issues to the Clinton and Gore campaigns, was warned that writing The End of America would end her career. It didn’t. It became a New York Times bestseller. Now Outrages, which took her eight years to write, harks back to a past empire to see how such abuses begin.

“The way the state cracked down and aggregated new powers in 19th century Britain (and with America watching Britain): it focused on the bodies of women of all sexualities; it focused on the bodies of men who today we would call gay; it ignored lesbians altogether; it focused on cross-dressers; and it focused on speech,” says Wolf. “And so those are really important things to look back at and understand how the state chose populations to marginalize and create what Scott Long, the LGBTQ scholar and activist, calls a moral panic as a way to suppress dissent.”

The laws enshrined by the British Empire sent ripples throughout the colonies and set the tone for the ensuing treatment of women, queer folk and BIPOC people everywhere, from Australia and Canada to India and Africa. In many ways, modern-day homophobia, sexism and racism can be traced back to purity-obsessed laws that were designed to colonize subject bodies. For example, some activists believe that the modern day sexual violence against women, girls and gays in India is fallout from the anti-Hindu, pro-British Indian Penal Code of 1870, whose main goal was to prevent sedition. That code’s anti-sodomy law, which criminalized homosexuality, was only repealed in 2018.

“It’s like the state is right there evaluating the body and naming the body,” says Wolf. “It’s so important to go back and see that the secular modern state invented that law, and that you can trace it back to the public health success of managing cholera and typhus and filth and sewage. That prepared everyone to accept that the state has a role in mediating private relationships.”

The current pandemic has touched a nerve with Wolf, whose activism was galvanized by the AIDS crisis. “I recognize that we’re in a public health crisis. Of course, there has to be some state regulation. It’s not always bad. That’s not what the point of my investigation of typhus and cholera was suggesting. It’s just that it’s also a risk. I think continually about the HIV epidemic because terrible losses were suffered, but at that time, homophobes were using the language of infection to say: Quarantine these people, strip them of their rights, inform their sexual partners without their consent, crack down on this population. People were demonized using this language of infection, and the LGBT community fought back hard against state management of their personal choices; the community mobilized to get proper medical treatment, to get support for people who were sick; the community created institutions to support people who were suffering from HIV infection, and education campaigns for people to be responsible. The community managed the epidemic without everyone’s rights being stripped away. And that mobilization was voluntary and grassroots-oriented. And to me that’s really a model. That epidemic didn’t conclude with the state managing the lives of people who were suffering from that illness.”

I grew up in San Francisco in the ’70s at the height of LGBTQ activism. Harvey Milk was in office. It so imprinted me as a writer, it was a model of how to be an activist, and it was so inspiring to see that love was the mobilizing force of people who were rising up together to defend their rights and to have political influence, which was riveting to observe as a teenager.”

NAOMI WOLF

And so back to gay pioneer John Addington Symonds and why Wolf chose him as an emblem of such issues. During the course of this man’s life, Wolf says you can see the state whipping up homophobia and creating moral panic around sodomy as the worst thing men could do in order to cover up the real misdeeds of heterosexual men, which were being interrogated by the first wave of the women’s movement. Suffragists in the mid-late 1800s, she says, had discovered that straight men were trafficking and raping girls and young women on an “industrial scale.” So as a smokescreen for straight men, anti-sodomy laws were ramped up.

The Contagious Diseases Act was passed in 1864 as a way of regulating prostitution and preventing the spread of STDs in the British military. Women sex workers were subject to forced exams, as were gay men. “The state was using its powers to invade, you, shame you, lock you up,” she says. As a rape survivor, Wolf is drawn to Symonds and other gay men whose bodies were on the threshold of being invaded by the state. “It is terrorism when the state says what your body can do, who you can love, what gender you can be.”

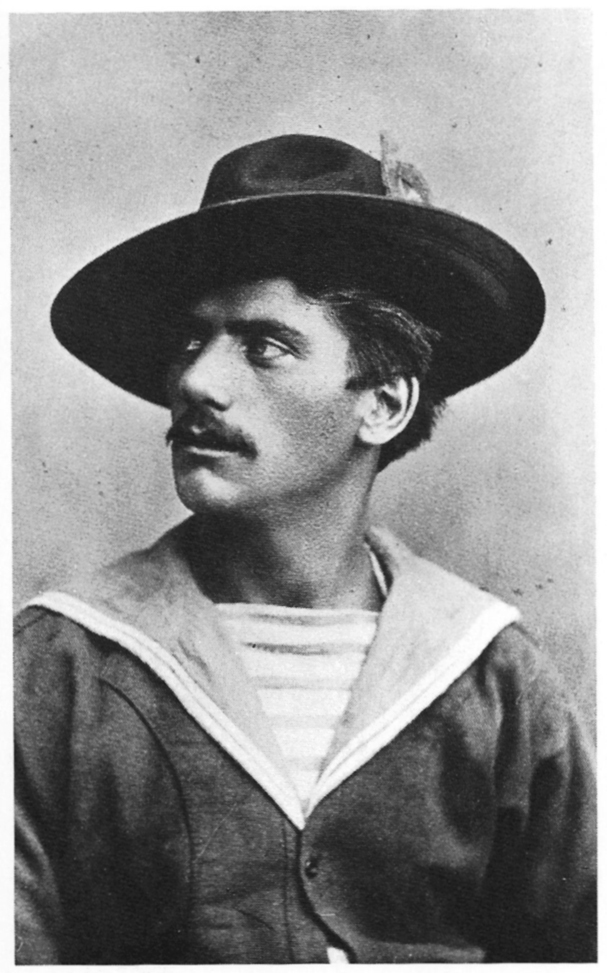

Symonds had an epistolary relationship with fellow poet Walt Whitman who led a (comparatively) more liberated life living and loving freely and writing about it, whereas Symonds mostly wrote in secret, married a woman and had four children before finally finding love with an Italian gondolier. “He believed in love. He was a great, great romantic,” says Wolf. “All of my books are about love at some level — and freedom. And that was what motivated him, the freedom to speak and the freedom to love and the freedom to speak about love. He never gave up.”

Angelo Fusato, Symonds’ gondolier lover

Annie Besant, women’s rights activist

Walt Whitman

“His refusal to give up his belief that love between men was noble and good and not immoral drove him his whole life. Symonds wasn’t naturally brave or constitutionally strong like Whitman. He was a timid man in poor health who was raised to be very conventional. And he faced real destruction in his professional life over and over again, to the point where he had to exile himself from his home and from his chosen profession and go live in Europe, which had more lenient laws about sex between men. In spite of danger and backlash, he tried to tell the truth.”

He wrote A Problem in Modern Ethics at the end of his life. It was illegal to publish it. It was illegal to distribute it. It was illegal to read it. “There were private reading societies for same-sex material,” says Wolf. “He wrote this manifesto aimed at jurists in Britain, making the case that there was nothing wrong with men having sex with men in the belief that some day there would be a society that accepted homosexuality.”

A Problem With Modern Ethics, published posthumously, was a bestseller and had a direct impact on the way we see sexual orientation as part of a natural spectrum. “He created that, even though he he never lived to see it, he never gave up faith in the art of writing and he never gave up faith in love,” says Wolf.

Find out more about Naomi Wolf. Purchase Outrages from your favorite bookseller or online here.

Naomi Wolf will be in conversation with Merryn Johns at the Saints and Sinners Festival on March 14.