Queer Black women of the Harlem Renaissance

Queer Black women had a central role in Harlem’s history and culture, says scholar Tara T. Green.

Tara T. Green is professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG) where she teaches literature and Black women’s studies courses. She holds degrees in English and her areas of specialty intersect with gender and Black parent-child relationships and/or Black leadership, activism, and liberation.

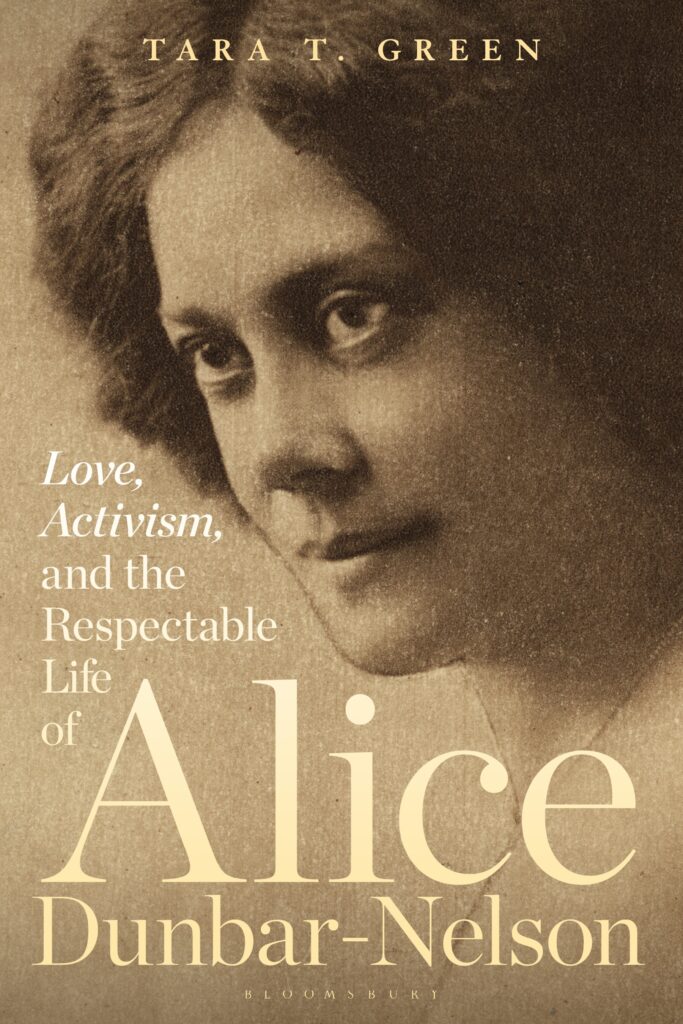

Dr. Green has two new books out this year. In her book about Alice Dunbar Nelson she explores how the queer activist, poet, and writer stood up against her abusive husband Paul Dunbar, took on a number of female lovers, and redefined what pleasure meant for herself, becoming a Black queer icon in the process.

Dr. Green’s second book explores the lives of Lena Horne, Moms Mabley, Yolande Du Bois, and Memphis Minnie — four Black women who despite being public figures were able to push boundaries and explore their own identities.

As a Black feminist, Dr. Green is reclaiming and centering these women at a time when Black queer women’s contributions to culture are of peak interest. We caught up with the professor to ask her a little more about her studies and work.

What personally drew you to the story of Alice Dunbar-Nelson?

Green: Alice Dunbar-Nelson was born in New Orleans in 1875. I am from the New Orleans area, but did not learn about her in any of my English classes or in the Louisiana history course. It was not until I was a student at Dillard University, an HBCU in New Orleans, that I was introduced to her work. It was also at that time that I learned she had graduated from Straight College, which would become Dillard University. She clearly loved her hometown. Her ability to bring historic New Orleans to life resonated with me as a reader who loves New Orleans and her work would remain with me as a literature professor.

How difficult or easy was it to collect and interpret the biographical details of her life?

Green: She made it easy. I suspect she wanted to be known, to be seen for who she was, prompting her to keep records of her life—scrapbooks, unpublished poems, short stories, etc., photos, letters, and diaries, which were inherited by her niece, Pauline Young who was a librarian and knew the collections’ value. Young made arrangements for the University of Delaware’s library to house the collection and that is where I did most of my research over a period of years.

There are timeline gaps, which I reference in my book, and at times handwriting is difficult to read, but thank goodness for typewriters because much of the material is legible.

Can you give us a snapshot of the contribution Black queer women made to the Harlem Renaissance? Do you have other figures you greatly admire who are book-worthy?

Green: The Harlem Renaissance was an era where we see a great deal of diversity among Black writers, painters, performers, and activists. Dunbar-Nelson’s career began in the century before the Harlem Renaissance. Therefore, her major contribution as an experienced and older writer was to spotlight the work of younger Black artists in her journalism as she also, at times, spotlighted the work of community activists and political injustices. As a gifted editorial writer, she used her platform to write about such writers as Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes.

Tracy Sharpley-Whiting has written about Black women who lived in France, some of whom were queer, such as Josephine Baker and Ethel Waters. I love the blues women of the era, such as Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. And, of course Lady Day (Billie Holiday). Angela Davis’s work on the blues women remains a must-read and I would love to see more on them as well as the Black Club women.

Dunbar-Nelson makes clear in her diary that some of the women were queer and used the opportunities of their travels to meetings to explore their same-sex desires.

I would also like to see more work done on the Dark Tower and A’Lelia Walker (See A’Leilia Bundles’ biography) who provided a space for LGBTQ individuals. Dunbar-Nelson visited the infamous salon at least once. My book, See Me Naked: Black Women defining Pleasure during the Interwar Era has a chapter on Moms Mabley, but she is certainly book-worthy.

Looking at today — who are the Black queer women you believe are making or will make future history?

Green: I teach and look forward to seeing some of my former Black queer students making “good trouble” in the years to come. Many were ignited by the 2020 summer protests and contributed to the Triad Black Lives Matter collection of oral histories. There are some local folks I know who are doing great work to improve the community and empower Black girls; I acknowledge them but also know that they may not want to be named. However, I will name activist Mandy Carter who is an icon in NC. On the national level, I lean in and take notes when I hear Raquel Willis speaking on trans rights.

About Tara T. Green

Inspired by her Southern upbringing, Dr. Green is a lover of storytelling. At UNCG, she works with librarians to expand the archival presence of the local Black community, including interviews with Black Lives Matter protestors and organizers for the Triad Black Lives Matter collection. She is the author or editor of six books. Her book A Fatherless Child: Autobiographical Perspectives of African American Men received the 2011 Outstanding Scholarship in Africana Studies Award from the National Council for Black Studies. In 2018, she published Reimagining the Middle Passage: Black Resistance in Literature, Television, and Song. She has edited two books, From the Plantation to the Prison: African American Confinement Literature and Presenting Oprah Winfrey, Her Films, and African American Literature. Her forthcoming books See Me Naked: Black Women Defining Pleasure During the Interwar Era (Rutgers UP) and Love, Activism and The Respectable Life of Alice Dunbar-Nelson (Bloomsbury) look specifically at how Black women of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century navigated the politics of respectability to live on their own terms.