The hidden pandemic: LGBTQ mental health

May is Mental Health Awareness Month and our community has to face a mental health crisis, especially for the over-forty.

Depression. Anxiety. Suicidality. This dangerous trifecta has stalked millions throughout the coronavirus pandemic, creating its own shadow pandemic. Recent studies from The Williams Institute at UCLA and the Movement Advancement Project show that a year of isolation has impacted LGBTQ people more that their straight and cisgender peers in a myriad of ways. More unemployment. More major financial hardships. More housing issues. More food insecurity. More health crises. And many more mental health problems.

The reasons would seem obvious: homophobia and transphobia impact every aspect of the lives of queer and trans people. Even in 2021, the layers of bigotry can still force people into some form of closeting. Trans friends have said that finding a job post-pandemic is going to be brutal for trans people in a market glutted with applicants. And in a hospitality industry that has been devastated by pandemic closures, the venues that have been a refuge for many queer people over decades may be less so as jobs are scarce.

May is Mental Health Awareness Month. It’s a time to evaluate LGBTQ mental health personally and within communities. Many people may not even know how much the pandemic has impacted their mental health and stability—or how their sexual orientation and/or gender identity puts them at greater risk for mental health crises overall. For centuries being LGBTQ has been associated with mental illness, criminality and a crossover sociopathology. Laws against sodomy were established in the 17th century in the U.S. and only overturned in 1993 by the U.S. Supreme Court. Committing sodomy was often used as an example of mental illness, so the connection between homosexuality as both mental illness and criminality was constantly being made and reinforced.

In the 20th century the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association is the handbook used by health care professionals in the U.S. and much of the world as the authoritative guide to the diagnosis of mental disorders. The DSM categorized homosexuality as a mental disorder until 1973 and being transgender until 2013. For generations, lesbians and gay men in the U.S. were also often imprisoned in mental hospitals for their same-sex attractions when families decided to have their sons and daughters committed rather than risk the social stigma of discovery. And to this day, conversion therapy is legal in every state for adults and in most states for minors. Currently there are more than 50 anti-LGBTQ bills in state legislatures. The Equality Act has yet to be debated in the Senate, despite being passed months ago in the House and President Biden urging its passage in his State of the Union Address. The stigma that attaches to being LGBTQ is still being codified into law with no remedy and the subsequent trauma may not even be acknowledged by most LGBTQ people—especially older queer and trans people who have been forced to adjust to discrimination and bigotry over decades.

Award-winning Black science-fiction author and Temple University professor Samuel Delany, 79, checked himself into a mental hospital in the 1960s. Fearing the homophobia of fellow patients, he was slow to reveal he was gay. Writing about his own experience, Delaney said what stunned him was his own self-loathing that he’d been unaware of. Delany wrote, “There in the hospital, I had not been dwelling on the physical pleasure of homosexuality, the fear and power at the beginnings of a political awareness, or the moments of community and communion with people from over an astonishing social range.” Instead, Delany had described his gayness as sickness and pain that he wanted to escape. He wrote that his perceptions that being gay was bad and harmful came from early readings in psychology that defined being gay as profound mental derangement and even criminality as well as novels in which being gay was something to hide and fear.

As Delany wrote in his novel Dhalgren, “As I walked home, I thought about the hospital again….It was so easy to tell your story and not mention you were homosexual. It was so simple to write about yourself, and just not to say you were Black.” Maginalization is a difficult path to traverse, and for LGBTQ people who are dealing with multiple areas of discrimination, like Delany, it can be an ongoing source of trauma.

Trauma therapist and social worker Dr. Jennie Goldenberg has worked with LGBTQ clients for nearly two decades. The interconnectedness of social stigma for being LGBTQ and the social stigma for being mentally ill makes seeking help for depression or other mental illness far more difficult than for a non-LGBTQ person, Goldenberg explained.

I believe the mental health field has not addressed adequately the need for interventions designed specifically for the challenges LGBTQ folks face in a still homophobic society.

Dr. Jennie Goldenberg

“The stressors and stigma continue to be crushing, despite high-profile celebrities and political figures like Ellen or Pete Buttigieg,” says Goldenberg, who addresses what Delany was unaware of at the time he spent three weeks in Mt. Sinai Hospital decades ago. “Because LGBT folks have significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression, due to their minority status, harassment, and so forth, the challenge is for MH providers to step up.” These providers must “help clients recognize that a lot of their stress is due to environmental/macro-level homophobia and transphobia…rather than internalize the negative and hurtful messages of society as personal failure and self-blame.”

Self-blame is the reason many LGBTQ people still seek out conversion therapy, even though it has been widely debunked. A survey by The Williams Institute of UCLA Law School showed that nearly half a million Americans had undergone conversion therapy as minors. The statistics on the lived reality of LGBTQ people and how discrimination, stigma and trauma have harmed them are both staggering and unsurprising. LGBTQ people suffer from more mental illness while also having less access to health care.

Studies show that among LGBTQ adults, 61% have depression, 45% have PTSD and 36% have an anxiety disorder.

Queer and trans people are more likely to contemplate and/or attempt suicide than their straight and cisgender peers across all ages groups. Recent studies suggest those numbers are as many as ten times that of non-LGBTQ people. And new research released last year shows suicide is at a 30 year high.Suicide is common in America—the 10th leading cause of death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Trevor Project reports that among self-identified LGBTQ people aged 10 to 24, suicide is the second leading cause of death.

In a 2016-2017 survey from HRC, 28 percent of LGBTQ youth and 40 percent of transgender youth said they felt depressed most or all of the time during the previous 30 days, compared to only 12 percent of non-LGBTQ youth. The numbers are also dramatically high among middle aged and older LGBTQ people. The CDC cites suicide as the fourth leading cause of death among LGBTQ people 35 to 54. Those numbers are double for women, even though more men commit suicide overall. The CDC reports women 45 to 64 have had the highest increase in suicides between 1999 and 2014.

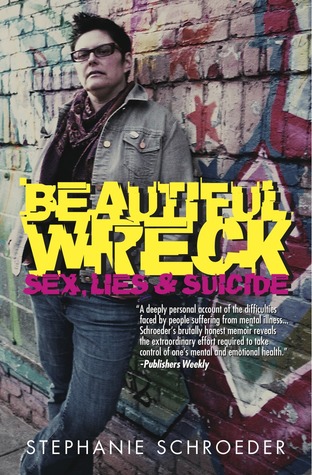

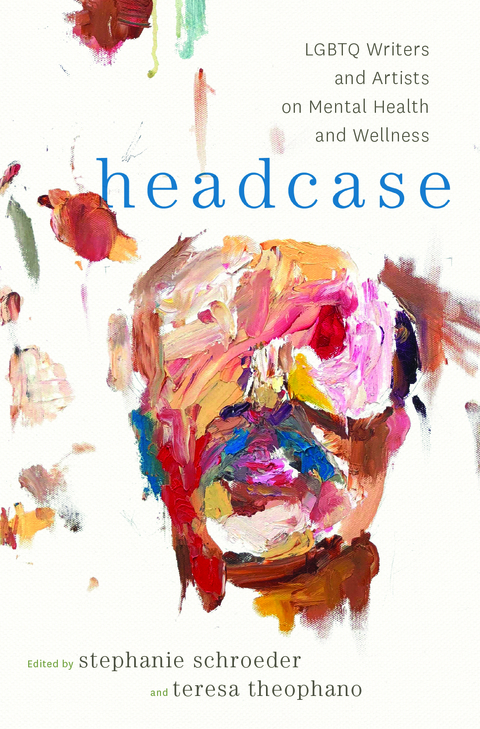

America has left most people with mental illness to fend for themselves. It’s far worse for LGBTQ people, as writer and mental health activist Stephanie Schroeder explained to me in an interview. Schroeder is co-editor of the groundbreaking anthology, HEADCASE: LGBTQ Writers and Artists on Mental Health and Wellness and detailed her own mental health struggle in her memoir Beautiful Wreck: Sex, Lies & Suicide. She reveals it was “pretty damn hard to get life-saving treatment” and she’s “a well-educated middle-class white lesbian.” But she added that “obtaining meds and not having insurance” can be a literal killer for LGBTQ people. Schroeder explained, “Queer people are at the bottom of the social ladder, facing every single barrier to getting the help they need. We have to work on that, because there’s a crisis out there that is not being met.”

New research from the Yale School of Public Health found that LGBTQ community centers may be the best conduit for access to mental health resources for LGBTQ people, providing a safe atmosphere of community, understanding and help. “Our findings suggest that LGBTQ community centers are vital to the mental health of this community,” said John Pachankis, Ph.D., the Susan Dwight Bliss Associate Professor of Public Health and director of Yale’s LGBTQ Mental Health Initiative.

The breadth of the impact of the pandemic, the long history of wrong and substandard care and the concomitant realities of homophobia and transphobia are real and oppressive. But efforts are being made by both private providers like Goldenberg and researchers like Pachankis to find inroads into care, while writer/activists like Delany and Schroeder illumine their own experiences to help others. Reaching out for help is always a first step. “We are excited about the potential to continue working with LGBTQ community centers to address and improve mental health outcomes in the LGBTQ community,” said Pachankis. “The need is great and community centers are one way that we can make real progress.”

If you are in crisis, call the Trevor Project hotline at 1-866-499-7386 or the SAMHSA’s National Helpline 1-800-662-HELP (4357).