How social media revived the bitchy queen stereotype

The ‘bitchy queen’ is back. This homophobic and scathing but self-loathing stereotype has risen from the dead thanks to cancel culture and social media snark. Now what should we do about it, as a community?

The hateful Madonna memes were spread over social media like graffiti feces. It wasn’t enough that gay men felt compelled to react negatively to the star’s ‘new face’ (most of the people posting were around the same age as Madge)—it was that they did it with whiplash precision. Hate is played like a video game now, the targets changing by the minute.

A pop culture article I wrote about five years ago (for a different queer publication than this one), was reposted on Facebook, and I glanced at a few new comments underneath. Not only did I read that I was a fucker for writing a story that, it was clear, most commenters hadn’t read, but one “critic” posted that I should be shot in the face ASAP. (He had lots of laugh and heart emojis attached to his remark.)

Then there’s that friend of mine, on Twitter and Facebook, who spends his days fighting off his “enemies,” his feed filled with scribes of remarkable nastiness going both ways. I sometimes wonder when any of them sleep. And if one side truly thinks they’re winning.

Elsewhere, in the literal world, a longtime acquaintance of mine walked by with a friend and snickered at the sight of me, part of some game he’s been playing ever since I disagreed with him on some topic or the other, the subject of which I’ve long forgotten. Whenever I do see him my first thought is that he must be exhausted keeping up the one-sided competition. My second thought is how much precious time he’s wasting.

And in Los Angeles, where I traveled recently to visit my 90-year-old ailing mother, a millennial at a popular gay bar told me to come back on Tuesdays—Grandpa Night. When I told him he shouldn’t be rude to strangers, he replied that I was tragic for hitting bars and whoring around at my advanced age. Funny how it’s always the younger crowd who know how one is supposed to act at an age they’ve not yet reached.

I’d say we should bring Valentine’s Day back for another round, but everyone already hates that holiday.

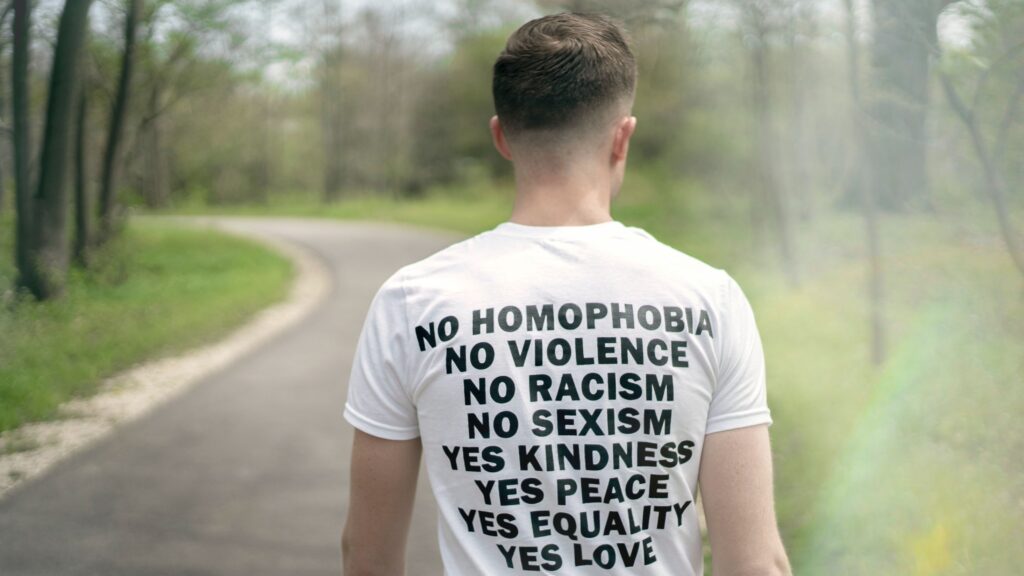

People say I shouldn’t be surprised at the cruelty of gay men in modern times, and I’m certainly past giving social media a peace chance. (For the record, I’m aware that straight people are unkind too, but I don’t document their endeavors.) But, as someone living in “advanced” years, I always thought we would have walked out of the carnage with kinder hearts. I don’t think of equal rights as just being about having the same freedoms as everyone else, I think it’s also about developing an equal awareness of the dangers of hate. Weren’t we supposed to leave the ‘80s and ‘90s with a stronger resolve and a determination to be better than what we’d left behind?

Surviving AIDS and the hatred that came with the times should alone make us realize how precious every moment of kindness is, and all that discrimination we faced should make us appreciate what liberties we’ve earned. But if our satisfaction is there, for the most part, it’s hiding under a rock. And our younger brothers and sisters, well, oy. Last I checked, they were telling people they were either whores or prudes and not realizing either choice is okay. Or that having the time for such arguments, ditto social media spats, means they’ve got a pretty good thing going.

I don’t expect Utopia, and whenever the subject of gay hatred comes up, friends remind me of the days when The Boys in the Band ruled the world. Self-loathing, they tell me, has always been a part of our history. But here’s the deal: Those characters were born in a world where being gay was just about the worst handicap to be dealt. Their real-life counterparts had every reason to be hateful. I’m no Pollyanna in regards to human rights, either, and I know we’ve got a long way to go. But things are much better on the political front than when I was the age of 10, 20, 30, and I wish I felt it more on the street, at events, on my computer. There are times I think we’re hopelessly self-destructive. Maybe it’s human nature, like every other tragedy playing out on the news in front of us.

It’s an ironic state of affairs when the most life-affirming gay stories of late are both apocalyptic: Murray Bartlett and Nick Offerman as doomsday lovers in The Last of Us and Jonathan Groff and Ben Aldridge as doomsday lovers in Knock at the Cabin. You’d almost think Hollywood’s sending a message that gay men are only supposed to thrive when the situation’s bleak—or that we’re the only ones with the right stuff to make it through fire and rain. Cause under difficult situations, thrive we do.

But on the screen, as in real life, our best selves shouldn’t have to wait for a storm in order to huddle together. This is the calm, before whatever happens next, so shouldn’t we use it to build a kinder, gentler world—it’s a sad state of sad affairs when I’m quoting George Bush. I’m no saint, and sometimes I forget to be as appreciative as I could be, so I’m going to be extra cautious about my behavior, about thinking before speaking, about making sure my friends know how much I really do love them. About letting the little stuff go.

If you’ve ever huddled around a dying man, or come close to dying yourself, or survived any kind of physical or emotional trauma, you probably know what it’s like to feel a sense of euphoria at the new chance you’ve been given—that need to savor every minute while it lasts. The elevated state can’t last forever (material matters set in), but the lessons can. If you don’t learn now how to utilize those tools you’re going to feel awfully silly when the apocalypse does hit and you’re stuck regretting how much time you spent sulking about the things you don’t have, bitching at brunch, and sending out mean tweets. You’re going to wish you had more times.