Women’s History Month: Maddy Gold, a life in art

From star-crossed teen lovers to life partners, here is a look back at the legacy of late lesbian artist Maddy Gold, from the point of view of her wife.

Since 2020, I have been reporting for Queer Forty on the importance of LGBTQ history. I have done numerous interviews with queer and trans people about their work and their own personal histories. In my February cover-story interview with E. Patrick Johnson, I delved deeply into an issue I have been writing and talking about for more than 20 years—the crucial need for oral histories of LGBTQ people. Johnson, who has been revolutionizing the field of oral histories in academia, spoke to me at length about why this is such a critical juncture for oral history: quite simply, people are dying. Johnson said re-creating a history of someone after their death is not the same as talking to them about those events in real time. His oral histories of Black gay men in the South are breathtaking in their realness.

I was reminded of this fact that Johnson put so succinctly—people are dying—after my 2022 interview with lesbian entrepreneur and writer, Leslie Cohen. My interview, in advance of publication of her memoir, The Audacity of a Kiss, appeared here in March 2022. She died suddenly mere weeks after our hours-long talk. She was 75. I was stunned by Leslie’s death. We’d had a wonderful, animated talk and had made plans to talk again. And then she died. There had been no urgency in our conversation and I have come to realize that this is a wrong approach: We need to view our lives as we age and the telling of our unique queer and trans stories with far more urgency. No one can tell our stories the way we can and it’s quite possible that no one will be there to tell that story. A year after my interview with lesbian historian Joan Nestle I am still thinking about it. Nestle is 84 and her health has been declining. Yet she was in her 30s when she had the prescience to co-found the Lesbian Herstory Archives in the 1970s—acutely aware already of how much lesbian history was being lost every day.

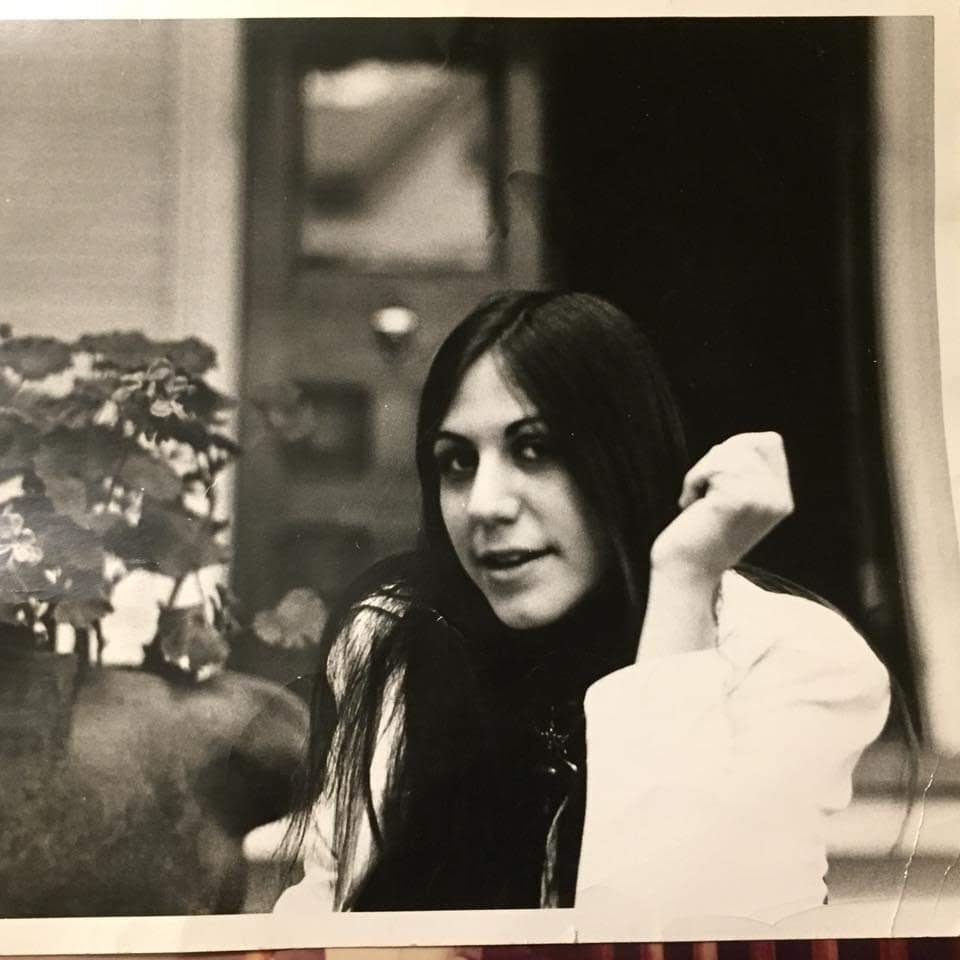

For nearly 25 years I lived with and was married to the lesbian artist, Maddy Gold. But I had known Maddy since we had met on a public transit bus on the way to our high school, The Philadelphia High School for Girls—popularly called Girls’ High. Our meeting and all that followed was emblematic of an extraordinary time in the midst of political tumult. And we would ride that national turmoil together as star-crossed teen lovers.

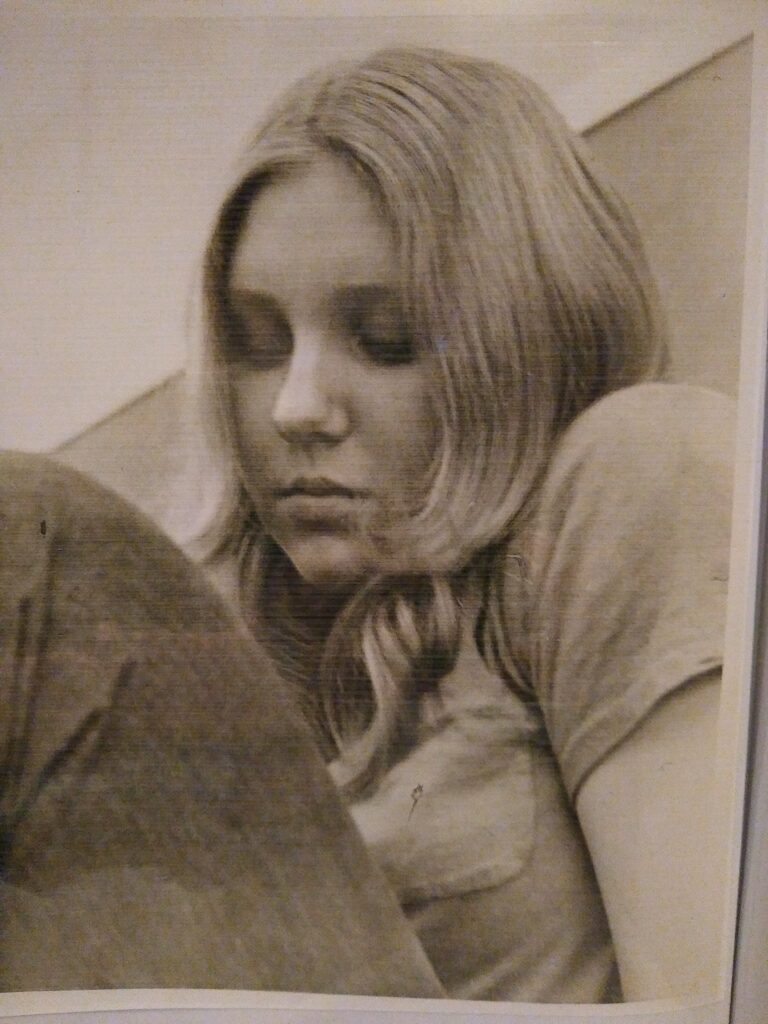

Two years into our relationship I would be expelled from our high school for being a lesbian, put in a mental hospital for conversion therapy and banned from seeing her. As she would tell me years later, when we were married, and I asked her why I was suddenly banned without a word of explanation from her house where I had spent so much time: “The mothers got together and put the word out on you. You were a threat. They thought you were this sweet, quiet blonde girl who was their daughters’ friend, but you were really this dangerous baby dyke, preying on their innocent daughters and luring them into the demi-monde.” It was, she said, a means to close off any discussion that their own teenagers might be gay if I was the villain of the story.

Having known Maddy for so many years and through so many different chapters of our lives, I am uniquely situated to be her biographer. I was, as she always told me, her first love and the love of her life. During her chemo treatments in 2022, to which her brother, composer and musician Robert Gold, took her, they were reminiscing about their teen years and he asked her, using the nickname I’d had at that time, if Maddy had ever been in touch with [nickname] again. She texted me, “Wait till you hear this! Bob just asked me if I’d ever been in touch with [nickname] again.” I texted back: “WHUT?!” She said: “Right??? I said, ‘I married her.’” For over two decades he hadn’t realized that his sister’s wife was that same girl who she had been so crazy about in high school.

Maddy was an artist from birth—or so her parents, who were both artists, told me at different times. Her father, Albert Gold, was an official combat artist in Europe during World War II. His work is in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art as at the Musée Galliera in Paris and the Pentagon. Maddy’s mother, Aurora, is a landscape painter. Both were art professors at the Philadelphia College of Art, now University of the Arts. Maddy also taught there for 35 years, starting after she finished graduate school at the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

Maddy was making art from a very young age, some of which Aurora collected. By the time I met her as a freshman in high school, Maddy was already on her career path, an art major at our academically accelerated high school. She was enrolled in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Saturday school for gifted young artists. And by the time we were sophomores, she was teaching young students at a local art camp. Her work was always stunningly different from that of her peers as well as her parents and reflected her eclectic use of materials and imagery. She was a voracious reader and given to purloined lesbian pulp fiction she got from her father, who seemed to intuit early on that his daughter was gay. Early in my relationship with Maddy he asked me, as I stood in the family living room waiting for her to come downstairs, what my intentions were toward his daughter.

I’ll never forget how the question made me blush, even then. But I don’t know what I said. I just remember her coming downstairs at that moment, her straight, waist-length black hair swinging behind her, and the conversation was over. We went upstairs to her bedroom and the sultry jazz she played in a room unlike that of any other teenager I knew: A dress form in the corner strung with protest buttons, filmy scarves over the bedside lamp and sketches and half-finished paintings and drawings everywhere. It was already the garret of a sophisticated artist.

I had asked Maddy when we first knew each other what she wanted to be and she said, “I’m an artist.” Not “I’m going to be an artist,” or “I want to be an artist,” but “I am an artist.” It was so succinct: There was never anything else. She was that sure of her work and her drive to create. The Gold household was filled with art—her parents’ as well as the work of other artists her father had collected while in Europe and after—Käthe Kollwitz, Giorgio De Chirico, some local artists.

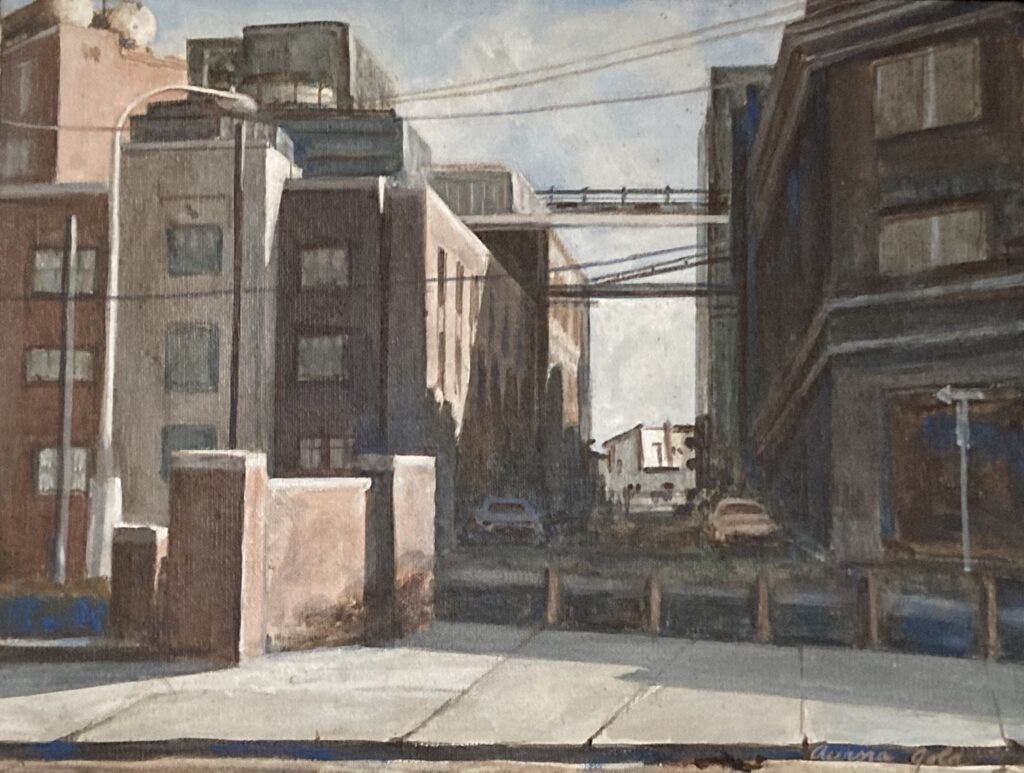

Artwork by Maddy Gold

The organic clutter of found objets d’art that filled that house and gave it an atmosphere that I found enchanting as a teenager was reflected in Maddy’s studio, but not her work, which was detailed and organized and incredibly disciplined. Her masters thesis was 25 large paintings she named whimsically after the noir works she had loved since junior high and the noir films we had seen together at the Bandbox repertory theater in Philadelphia. Post-grad Maddy began showing her work at galleries in Philadelphia and New York.

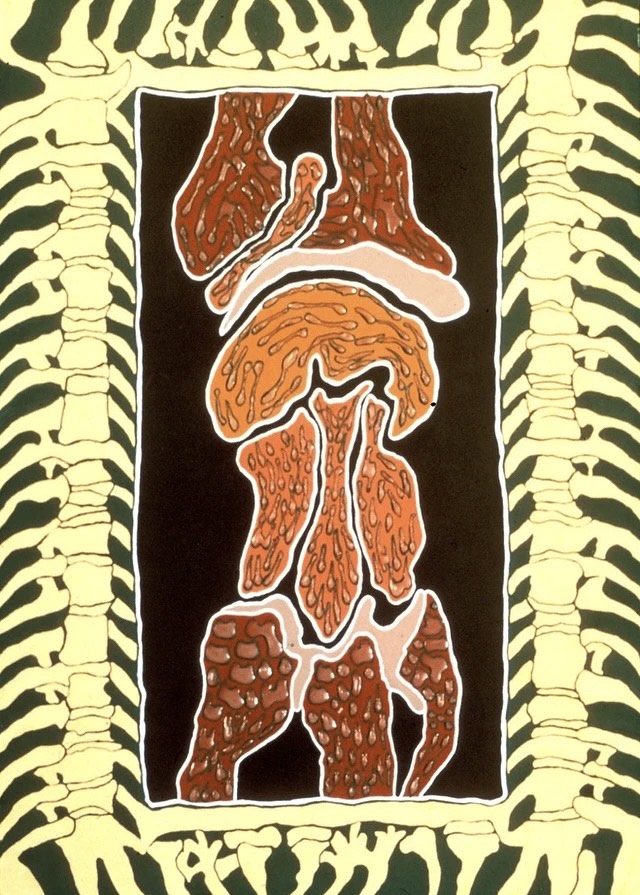

Her work got larger and more complex. She told me that her desire was to create totems—painted sculptures that were invested with their own personae and which she saw as intrinsically female. Some of the pieces from that period, which she cut out of Masonite, are over six feet high and many have a breadth to them that is at least four feet.

Experimental filmmaker Judith Redding, Maddy’s closest friend, had long discussions with her about her work. In an interview with Queer Forty, she said, “Maddy’s inspirations included the artwork of naturalist Ernst Haeckel, cartography, and traditional indigenous art, especially that of Australia. She was fascinated by the symmetry of bones and skulls, and did a series of paintings incorporating them.”

Diane Felcyn, a curator and art historian who knew Maddy for over 20 years, said in an interview, “Maddy’s art was a direct reflection of the things that fascinated her. She loved experimenting with color and color harmonies. More specifically her art demonstrates her fascination with fractals, science, biomorphic forms, insects, anatomy, realism and the Dutch masters. Something that looks like an abstract painting at first, could actually be a realistic representation of a microscopic image or bone that fascinated her.”

Felcyn said, “Her deep color palate is an inspiration from the reverential way a composition would appear in a classic Dutch still life. Like Maddy herself, her artwork is multi-layered and becomes more revealing of her passions and personality the longer you experience it.”

Maddy’s totem period lasted for nearly a decade until she was injured when a piece of Masonite fell on her, knocking her to the ground and breaking her back and ankle. Surgery to remove two crushed discs and fuse that area of her spine left her with permanent back pain and damage to her sciatic nerve which also made one foot numb.

Artwork by Maddy Gold

No more totems.

As Redding explained, when Maddy shifted from the sculptures to paper, the style and materials she used forced her work to become even more disciplined. “Maddy worked in gouache, which dries quickly, adding layer upon layer. When she wanted to add texture to a painting, she often mixed paint and glue, adding micro dots to the surface of the painting. It was painstaking and precise, but she had to work quickly before the glue set.”

The back surgery and long recovery led to a fascination with bones and bone structures and Maddy began painting these post-recovery. The passion for biometric structures continued to blossom. In the college courses she taught at University of the Arts and later at Drexel University, design became her new focus and passion.

She developed new artistic forms to work with—drawing complex forms and then working on getting the right colors to make those forms vibrate on the page. Maddy said often she didn’t want the colors to be “too pretty”—she said the work of women artists is often characterized as less serious than that of men purely on the basis of color choices. She said, “Too much pink in Mary Cassatt let men diminish how much better an artist she was than many of the men critiquing her work.” She favored the more declarative work of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, with her bold colors and huge shapes.

When the obituary I wrote for Maddy was posted on the funeral home website, more than 500 people wrote remembrances. In addition to President Biden and Pennsylvania senator John Fetterman, were hundreds of students with stories of how Maddy changed and shaped their lives as readers, artists and people.

Painter Mark Allen Natale talked with Queer Forty about Maddy. Natale’s perspective is unique. “I knew Maddy for many years, first as my high school art teacher, then as a close friend and mentor. She was the person who recognized my talent and opened my eyes to the possibility of art as a career. Maddy worked closely with me and was instrumental in helping me develop a strong portfolio to get into a university art school.”

Natale provided insight into Maddy’s other great love: teaching. “Her instruction was always much deeper than a typical art class. Time spent with Maddy was always filled with passion and love and I believe this is why she was always so revered by her students. I will always credit Maddy with directing me and all the success I have achieved.”

Work in Maddy’s studio

Natale owns some of Maddy’s work from the period where she focused on bones and ligatures as she worked through how the accident had changed both her body and her ability to work in the form she had been so deeply invested in. Natale said, “Like Maddy, her artwork is visceral, edgy and bold. Her paintings are a brilliant combination of organic shapes, anatomical study and two dimensional color and design theory. She playfully uses patterns of organic forms and rich complementary colors to create a visual buzz similar to that of an ‘Op-Art’ painting. Maddy’s three-dimensional wall forms are like microscopic organisms enlarged to a scale that makes them both frightening and intimidating. These carefully cut and painted wood assemblage pieces are organic but precise with colored dots carefully placed with surgical precision.”

During the pandemic Maddy and I spoke often of doing collaborative work post- pandemic with me writing text that would be situated within structures of moving sections of dots and other shapes that had become the focus of her most recent work.

Maddy herself was larger than life. She was voluble and took up a lot of space in a room, pacing back and forth as she talked or taught, arms gesticulating, all her conversation peppered with jokes and stories and bits of acquired knowledge she was eager to share, because she was a natural raconteur as much as she was an artist and professor. She was smart, funny and immensely, prodigiously talented.

Redding said, “After Maddy’s death, when I went into her studio I found a plethora of paintings and totems I had never seen before. Her output was prodigious, and she was painting until her death—even cancer did not stop her from creating.”

Of the painting, “Plump Stuff” that her father did of her, Redding said, “Although she was only a toddler when this was painted, it captures the essence of the adult Maddy as well: alert, staring calmly at the viewer. She used to joke her expression, watching her father, was ‘What do you want, Old Man?’”

When the poet Mary Oliver’s artist partner of 40 years, Molly Malone Cook, died in 2005, Oliver began memorializing her and her work. Soon after Maddy’s sudden death from cardiac arrest just six months after she’d been diagnosed with that rare, aggressive stage 4 cancer and while she was undergoing brutal surgeries, chemo and radiation to, as she said again and again, “stay with you, stay with us, and start our next chapter,” I read Oliver on Cook and realized that my role as lesbian widow was in part to memorialize Maddy, our long love affair, and her work as an artist. Thousands of people have read and shared the story I wrote here just weeks after her passing. Last June I wrote about how as teenagers we attended the first Pride march in Philadelphia together.

Now I am intent on making sure Maddy’s art, for which she’d won numerous awards—an National Endowment for the Arts grant, a Ford Foundation grant, a Pennsylvania Council on the Arts grant, and had held one-woman shows at the Institute for Contemporary Art, the Pratt Institute, the Perleman Gallery and the Art Alliance of Philadelphia as well as having been in numerous group shows—receives new attention in the form of retrospective shows in 2025 and 2026, a book and an annual award to an emerging lesbian or queer woman artist.

One point Johnson made to me repeatedly in our interview about our LGBTQ histories is that “historiography” is crucial and that “oral histories give nuance to historical events” that can’t be gleaned from “a newspaper clipping or a Playbill.” He said speaking to people who were there in the moment of an event has deep resonance for people who weren’t part of that time.

I was there in that long journey of Maddy Gold’s life and art. I want what she accomplished and the impact she had on students, friends, family and me, to resonate for years to come, as people view her art, read her story and use it to propel their own work forward.

To contribute to the fund for an annual grant, send checks to: The Maddy Gold Emerging Artist Award, 311 W. Seymour St. Philadelphia, PA 19144.

Amazing story, well told.

What a lovely tribute to an amazing artist. And how lucky you both were to spend so many loving years together.