Unlike Cher, I don’t want to turn back time

My thoughts on the joys of aging, and the illusion that things were always better when we were young.

After my regular hookup and I were finished with a sweat-filled fuck-fest, he rolled over and said, “I Googled you and found some old pictures. You must have gotten any man you wanted back in the day.”

I looked at Michael, a guy so sexy he would have made my 16-year-old heart flutter, and replied, “Trust me: It’s better now.”

I was pretty sure I knew the photo Michael was referring to, from 20 years ago, because of the compliments I still get on it, and with them the inevitable, “I wish I knew you then!” remarks. Everyone wants to be with that guy now, one former flame saying he wished I could turn back time.

Yeah, it’s a good photo, but like so much of our gay lives, it’s romanticized to the extreme—sometimes even by me.

I’m not sure where or when gay youth became equated with a utopian existence—the Greeks, perhaps—but, at least in my life, physicality and youth have had little correlation with my happiness and emotional well-being. They’ve often been detrimental.

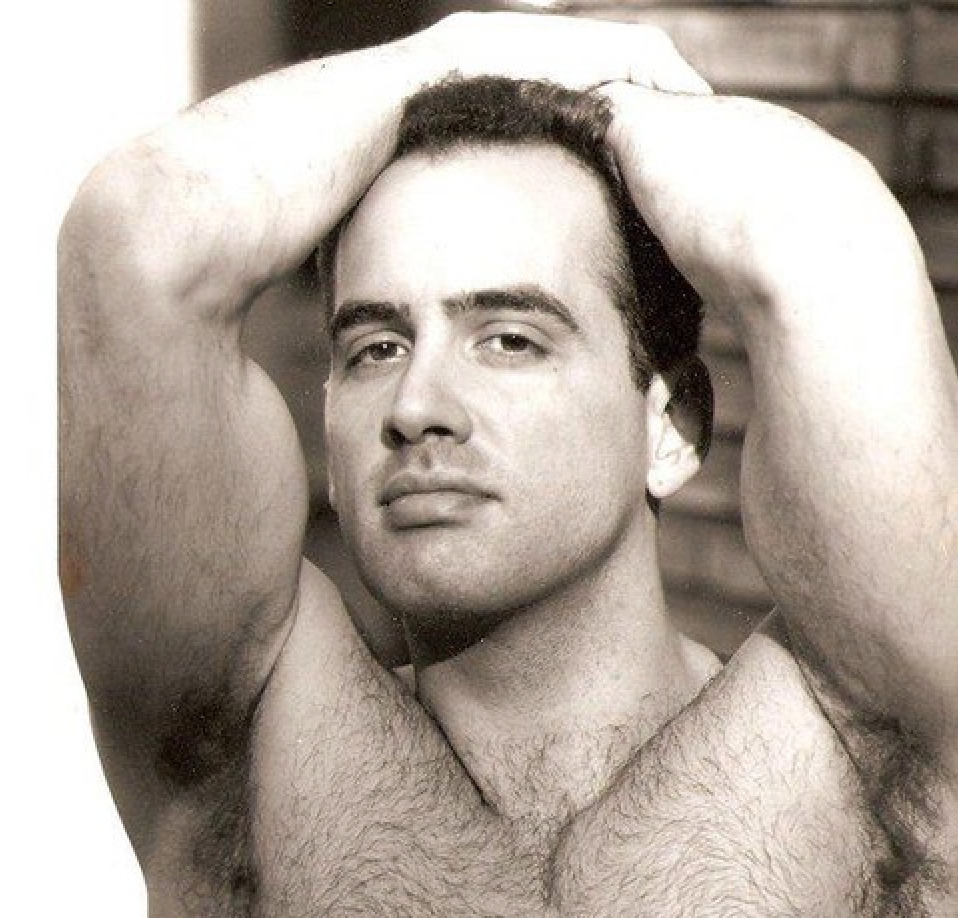

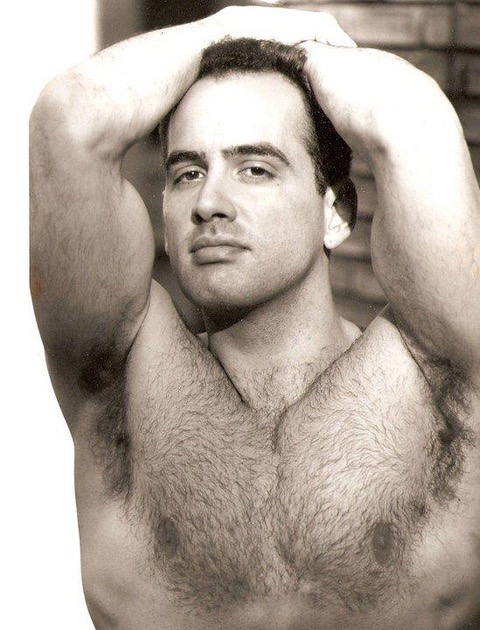

I was 37 in the photo in question, and the circumstances surrounding the shot are events I’d rather not revisit. Taken in the Hamptons on a cold winter day, I was having a miserable time with my boyfriend, whom I’d outgrown, and we’d been fighting all day. I disliked his friends, hated being out in Long Island—his home—and was fighting a vicious hangover that was a daily occurrence. My boredom needed chemical solutions, further necessitated because, come Monday morning, I’d be back at my tedious job with a boss who insulted my writing and me on a daily basis. What’s worse, on reflection, is that I hid the photo for years because I thought I looked fat.

I realized a little later on that Michael might have been referring to another photo of me that shows up on Google searches taken, ironically, almost exactly a decade earlier. In that photo, shot on a West 22nd Street rooftop, I’m shirtless and my arms are over my head. I was deliriously happy that afternoon, living in the land of Chelsea Boys, hanging out at trendy gay bars, and pursuing an acting career in gay wonderland. I also still had a full head of hair and a 28-inch waist. I wouldn’t trade those days for the world, but I don’t wish for their return.

What we often forget, and what baffles me when I hear gay men my age saying everything was better “back in the day,” is what we didn’t have: a voice. In addition to AIDS decimating half the people on the streets below that rooftop, we risked gay bashing every time we headed to another club—on a walk home from the Roxy one early morning, my friend and I watched the man in front of us get beaten to a pulp with a baseball bat. Most of the friends I made had traumatic coming out stories, and many had been abandoned by their families altogether. Yes, it can still be a struggle growing up gay, but, to paraphrase the expression, “It got better.”

I didn’t see men getting legally married, let alone having children, or having visitation rights to visit dying partners in hospitals. I didn’t see an openly gay man in a presidential cabinet, but I vividly remembered Harvey Milk’s assassination and his murderer getting a pittance of a sentence—damn those Snickers bars and their killer ingredients. (If you don’t get that reference, in the immortal words of Madonna, “Look it up!”) Even the little things were often a pain in the butt. Remember connecting with men via AOL chatrooms? The dial-up struggle was real!

If The New York Times same-sex weddings seem ho-hum now, along with Corporate Pride, or if they’re against your own views on hetero-normal behavior, it’s nice to know that once-impossible goals are now reality. Coca-Cola likes us, they really like us. Being a sought-after consumer isn’t demoralizing, as some queers lament; rather, like the focus-grouped jingle for gay self-acceptance, “Born This Way,” it’s a sign of our monetary strength in a world built on advertisement.

As for my own professional aspirations, most agents and casting directors avoided me in my 20s, because I wasn’t shy about my sexual orientation. Unless you were Nathan Lane (who wasn’t out yet—seriously?), any sign of sexual fluidity had to be kept in the closet with the glitter. In similar fashion, we didn’t have the gay-friendly roles that are in abundance today. Now I see out actors like Ben Platt and Zachary Quinto play roles I would have killed for.

I’m still in a heavenly haze watching shows like Sex Education and Love, Victor, series that feature gay kids struggling with the normal pangs of growing up. And virtually every television show has sexually active gay or lesbian characters

Certainly, no one’s gonna drool over my teenage-years photos, and, like most awkward, athletically-deprived gay kids, my youth was suburban hell. There’s a Facebook group that celebrates the glory days of my high school, and every time I read alumni posts of their once-perfect world, I wonder how oblivious the jocks were to the torture they inflicted upon people like me. Heck, most probably enjoy the memory of terrorizing “that faggot Toussaint.” I’m not going to even attempt to understand what gay youth endures today, with social media and mass shootings, but I wouldn’t go back to that time for all the Playgirl centerfolds in the world.

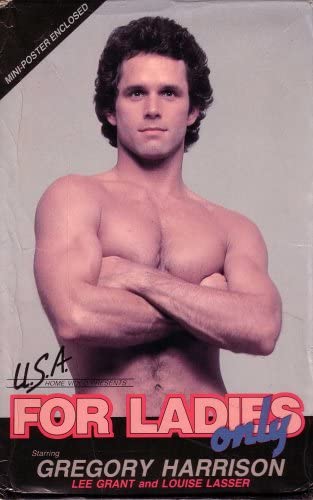

In case you didn’t get the Post-It note, our role models were fantasy-based, drooling in private over men like Gregory Harrison in the straight-male-stripper flick Ladies Night. Our youth was an attempt to be an alternative-reality version of ourselves, struggling to convince the parents, the teachers, the friends, the neighbors that we were just like them, even if it killed (a few of) us, often only in masturbation being true to ourselves.

For my generation it usually comes back to sex, because it was the missing, key ingredient of our lives, its gravitational pull cut off from the start. We made up for it, big muscles and bigtime, and by the time I’d turned into the guy I wanted to take me to the Senior Prom, my gym and its rival campuses, Chelsea, and Fire Island were my hormone-dipped playground. The sex was great but, like most everything except the outer layer, it got better with age.

So when Michael talked of past, presumed conquests, I thought of how much that aspect of my life has excelled over the years. PrEP and U=U hit just at the right time, at least for me, and Daddies became a cyber rage party. I also learned that pleasuring your partner is, literally, half the fun, especially when bareback became a once-unthinkable option. I bloomed at 50, discovering a whole new bounty of men that I was too insecure to approach when I was half my age. I grew far more comfortable with my face and body, and no longer feared rejection or moped over the fact that, no matter how hard I tried, there would always be someone prettier than me. I was good enough all by myself or in a group of men fucking together. It’s not that I wouldn’t have gone to a sex party in my 20s or 30s; it’s that I would have felt too ashamed to admit it.

I resent people telling me it’s downhill from here (whatever age “here” is is up for debate), and I believe glorifying the past is dangerous in that it infringes on the beauty in front of us while simultaneously ignoring progress. Memories are to save and to celebrate, on the condition that we’re reliving them in the moment of today.